The collapse of the Ming Dynasty resulted from a mix of ineffective governance, environmental disasters, economic difficulties, and widespread rebellions that weakened the state, allowing the Manchu Qing to take power through strategic alliances, military strength, and political acumen.

The Ming Dynasty’s decline began notably during the reign of the Wanli Emperor (1572-1620). Wanli initially benefited from the reforms and treasury improvements of his regent, Grand Secretary Zhang Juzheng. After Zhang’s death in 1582, Wanli retreated from active governance. This withdrawal left administration largely in the hands of corrupt eunuchs. Such government dysfunction stalled reforms and worsened the dynasty’s ability to manage rising pressures. The government faced costly conflicts, including battles against rebellions and the Japanese invasion of Korea, which drained imperial funds.

Natural and economic crises compounded the problems. From around 1600 to 1644, a series of droughts and floods caused widespread famine. The Little Ice Age reduced crop yields further, leading to starvation among peasants. At the same time, plague outbreaks devastated the population, notably killing a quarter of Beijing’s residents. Complicating matters, the Ming tax system relied on silver, but the influx of silver from the Americas dropped sharply. As a result, taxpayers faced effectively higher taxes, fostering resentment toward the government.

Economic hardships and famine fueled massive peasant rebellions. Two notable uprisings included those led by Zhang Xianzhong in Sichuan and Li Zicheng near Xi’an. Li Zicheng’s forces gained momentum and eventually declared the short-lived Shun dynasty. These rebellions severely disrupted the economy and distracted Ming forces from defending the northern borders against external threats.

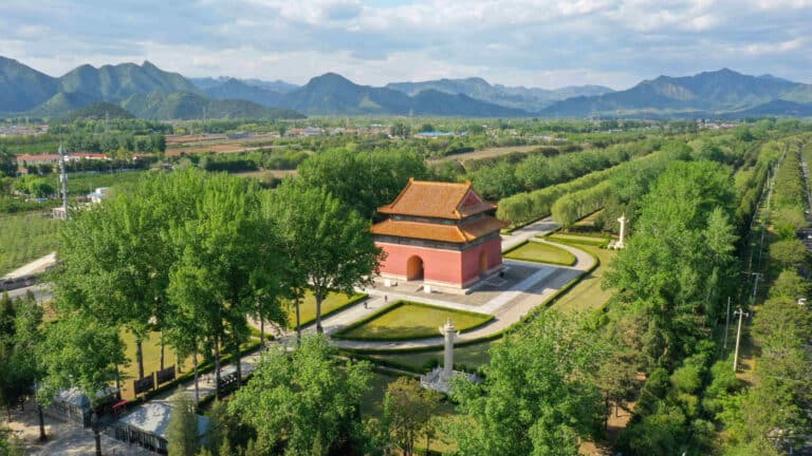

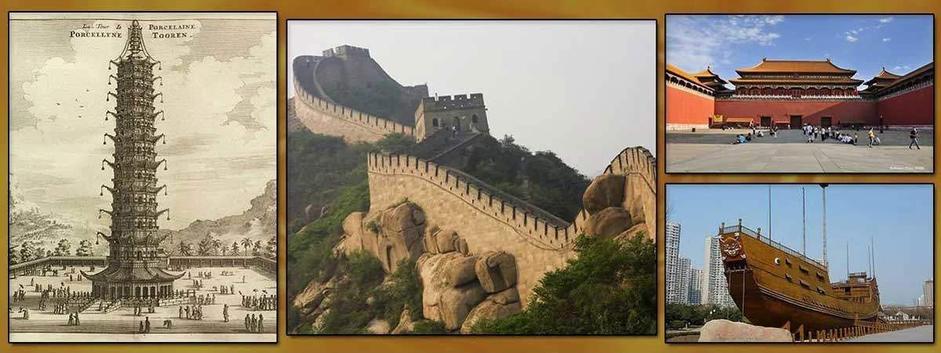

By 1644, the Ming military was fragmented and weak. The rebels, under Li Zicheng, marched on Beijing and captured the city with little resistance. Facing this crisis, the last Ming emperor chose suicide. At this point, Wu Sangui, a key Ming general stationed at Shanhai Pass on the Great Wall, controlled the gateway to the capital.

Wu Sangui initially hesitated when rebellious forces sent him an offer to join them. However, reports of Li Zicheng’s brutal behavior and the execution of Wu’s father shifted his decision. Wu allied with the Qing, a powerful Manchu force north of the Great Wall. This alliance proved decisive. Together, Wu Sangui’s troops and Qing armies defeated Li Zicheng’s rebel forces.

The Qing had a strong, well-organized military and were experienced in warfare. They exploited the Ming’s weakness and internal fragmentation. After gaining a foothold inside China proper, Qing forces progressively expanded their control. By 1663, the Qing had conquered nearly all former Ming territories and continued to consolidate power, including claiming Taiwan in 1683 after taking advantage of local succession disputes.

The Qing leadership, under Prince Dorgon acting as regent for the young emperor, showed effective political management. Dorgon opposed installing a direct Ming heir, maintaining Qing regency control and stabilizing their rule. This strategic leadership helped the Qing establish themselves firmly as China’s new ruling dynasty.

Key reasons for Ming collapse:

- Wanli Emperor’s disengagement and eunuch corruption weakened governance.

- Environmental disasters caused famine and population decline.

- Economic crisis driven by silver scarcity and increased tax burdens.

- Widespread rebellions drained military and economic resources.

Reasons the Manchu Qing replaced the Ming:

- Wu Sangui’s alliance enabled Qing entry into China.

- Qing’s strong military exploited Ming vulnerabilities.

- Political skillful leadership under Prince Dorgon secured control.

- Ming fragmentation and rebellion prevented organized resistance.

This transition illustrates how internal decay and external forces combine in dynastic changes. The fall of the Ming was not due to a single cause but a series of compounded failures. The Qing’s rise depended on seizing opportunity and forging crucial alliances that cemented their position as China’s rulers.

What led to the collapse of the Ming Dynasty? Why was the Manchu Qing the one to replace it?

Simply put, the Ming Dynasty collapsed because a perfect storm of bad governance, natural disasters, and rebellion battered the empire until it crumbled. The Manchu Qing replaced the Ming because they capitalized on Ming weaknesses through strategic alliances, military strength, and savvy leadership. Let’s unpack how this epic drama unfolded.

Imagine the Ming Dynasty as a grand ship sailing smoothly under the early Wanli Emperor’s guidance, especially with Grand Secretary Zhang Juzheng at the helm. Zhang was a fiscal whiz, boosting the treasury and avoiding costly battles. But after Zhang’s death in 1582, it was like the captain vanished on deck — Wanli basically retired without stepping down, leaving eunuchs to run the show.

Sound like a disaster waiting to happen? You bet. The eunuchs’ corruption worsened government efficiency. Meanwhile, expensive wars—like fighting rebellions and retaking Korea from the Japanese—blew a hole in the treasury. By 1600, the empire’s resources were stretched thin.

The Natural World Joins the Downfall

Mother Nature didn’t help. The last 44 years of Ming rule coincided with the harsh Little Ice Age. Droughts and floods ravaged crops, causing famine. If you thought that’s tough, a plague outbreak wiped out a quarter of Beijing’s population. Silver, the currency backbone, dwindled sharply when American miners slowed exports, hiking effective taxes on already struggling peasants.

This deadly mix created fertile ground for unrest. Hungry peasants refused to stay silent, sparking massive rebellions. Leaders like Zhang Xianzhong in Sichuan and Li Zicheng near Xi’an seized the chaos, stirring up anti-Ming forces. Li Zicheng’s crowning moment came when he declared himself emperor of the Shun dynasty and marched straight to Beijing.

The Fall of Beijing and the Last Straw

By 1644, the Ming were too weak to hold the capital. Beijing fell almost effortlessly to Li Zicheng’s rebels. The last Ming emperor, overwhelmed and isolated, took his own life. Fragmented and demoralized armies failed to mount effective defenses. As Beijing tumbled, the stage was set for the next player to enter the scene.

Enter Wu Sangui and the Manchu Qing

Here’s where history throws in a twist — Wu Sangui, a Ming general guarding the critical Shanhai Pass at the Great Wall, faced a dilemma. Rebel leader Li Zicheng sent him an offer to defect. Wu almost said yes but heard of the rebels’ brutality and that his father was killed by Li’s men. Deciding survival meant smart alliances, Wu threw his lot in with the Manchu Qing, opening the gates for their armies.

The Qing arrived with the strongest northern army, well-disciplined and battle-hardened. They wasted no time pushing beyond Manchuria into Chinese heartlands. They swept through the disorganized Ming remnants while absorbing defectors and generals, solidifying power swiftly — all by 1663.

Why the Qing, and Not Some Other Group?

The Qing weren’t just lucking into power. Their leadership, especially the regent Prince Dorgon, played master tacticians. Dorgon ruled through a child emperor, keeping regency power intact. Politically astute and militarily aggressive, the Qing exploited Ming internal weaknesses and rebel chaos perfectly.

Meanwhile, Ming loyalist resistance became scattered and ineffective. The Ming dynasty’s fragmented governance, economic ruin, and losses in manpower simply couldn’t stop the Qing juggernaut. Even overseas territories like Taiwan fell to Qing control, cementing their reign in 1683.

Lessons From the Collapse and Replacement

- Governance matters: Wanli’s reluctant leadership led to eunuch overreach and administrative chaos, showing how vital hands-on rulers or effective bureaucracy are to stability.

- Environmental factors: Climate change and disasters compounded political and economic woes drastically and rapidly.

- Military strength and alliances: Qing’s superior forces and Wu Sangui’s pivotal alliance altered the course of history dramatically.

- Rebellion dynamics: Popular uprisings can topple dynasties but missteps like Li Zicheng’s political errors can open doors for even colder conquerors.

To put it bluntly, the Ming collapsed because they were overwhelmed by a combination of poor leadership, natural disasters, and widespread rebellion. The Qing dynasty rose next because they exploited those failures efficiently, maintained a disciplined military force, and secured key alliances.

So, when you ask “What led to the collapse of the Ming Dynasty? Why was the Manchu Qing the one to replace it?”, it’s a story of slow decline mingled with dramatic opportunities grasped decisively. Sometimes history favors those who not only wield power but also know when to grab the right allies at the right time.

Isn’t it fascinating how the fate of an empire rested on a single general’s choice and one ambitious rebel’s error? History doesn’t just repeat itself; it also makes us reflect on leadership, resilience, and the unpredictable turns of fortune.