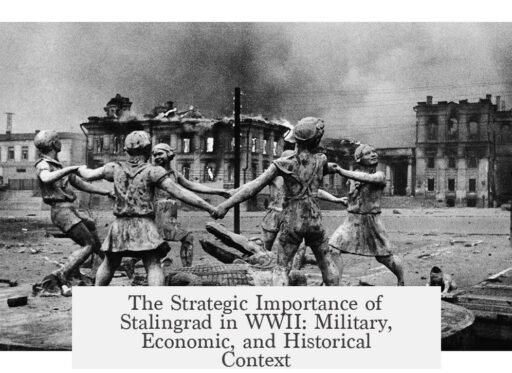

Stalingrad’s strategic importance during WWII stemmed from ideological, military, geographic, and economic factors. The city held symbolic meaning for both Nazi Germany and the Soviet Union, shaped operational decisions, and was pivotal in shaping the Eastern Front’s dynamics. Understanding these elements clarifies why Stalingrad became a critical battlefield.

First, Stalingrad had immense ideological and symbolic value. The city bore the name of Joseph Stalin, the Soviet leader, which made it a personal and symbolic target for Adolf Hitler. Capturing “Stalin’s City” was intended to demoralize Soviet troops and civilians. Hitler believed destroying this city would undermine Soviet morale while boosting German confidence. The city’s capture symbolized more than a military victory—it was designed as a direct affront to Stalin. Previous German bombing campaigns, such as those on London, aimed to break morale, and Stalingrad mirrored this tactic but on a deeper, ideological scale. It became a stand-in for German hubris and was seen as a battle where winning meant validation of Nazi dominance and losing meant catastrophic symbolic defeat.

Beyond ideology, Stalingrad carried substantial military and tactical considerations. Its location on the Volga River made it a crucial defensive and transport hub for the Soviets. The city controlled vital transport routes used to ferry supplies and reinforcements, mainly across the river. Originally, the German plan (Operation Blau) did not seek to capture Stalingrad directly but intended to encircle it and disrupt Soviet operations along the Volga. However, Hitler diverted massive resources to capture the city itself, shifting from the German army’s strength in rapid armored maneuvers to costly, grinding urban warfare. This shift nullified the Wehrmacht’s mechanized advantages and led to heavy casualties, including the loss of the German 6th Army—a devastating blow for Germany.

Geographically and economically, Stalingrad was significant due to its proximity to southern Soviet oil fields and agricultural regions. The war by 1942 had settled into one of attrition, emphasizing the need for resources. Capturing Stalingrad promised access to the Caucasus oil fields, especially those around Baku, one of the largest oil centers globally at the time. Seizing these oil fields was crucial for fueling the German military machine, which faced increasing resource shortages. Additionally, taking Stalingrad could have cut off grain supplies from southern Russia, striking a critical blow at Soviet logistics and food security. The city also served as a major industrial and railroad hub, capable of supporting Soviet troop movements and supply lines. Controlling it was strategically valuable for securing the flank of German advances into the south and east.

However, the battle’s strategic importance must be weighed alongside other significant wartime events. Stalingrad was not the primary goal of Operation Blau, nor was it the war’s definitive turning point. The belief that Stalingrad marked the moment Germany lost the war oversimplifies a complex conflict. The Wehrmacht had already faced setbacks by 1941. The decisive battle often considered more critical was the Battle of Kursk, which took place six months later and decisively halted German offensive capabilities on the Eastern Front. Still, in 1942, the German advance was about survival in the east. Army Group South aimed to eliminate the Red Army in the south to stabilize the front and secure resources. A decisive victory at Stalingrad might have delayed the Soviet advance and salvaged the German military situation.

Comparing Stalingrad to other strategic targets like Moscow also highlights its nuanced importance. Moscow was a political and manufacturing center, making it a logical military objective. But its capture in previous conflicts, such as Napoleon’s invasion, did not guarantee victory given Soviet resilience. Sieging Stalingrad was more complex; the Soviets held five armies on both flanks to block German crossing of the Volga, making a prolonged siege impossible. Some argue Hitler would have succeeded better by bypassing Stalingrad to push deeper into the Caucasus and secure oil fields directly. Ultimately, Stalingrad offered limited direct advantages but immense symbolic and operational challenges, contributing to its infamous status.

| Aspect | Importance |

|---|---|

| Ideological | Symbolized Nazi defiance and Soviet morale; a personal target of Hitler |

| Military | Key transport hub on Volga; urban combat negated German strengths; encirclement disaster for Germany |

| Geographic & Economic | Gateway to Caucasus oil fields; protected southern Soviet resources; industrial and railroad center |

| Wartime Context | Part of broader attrition war; connected to the survival of Army Group South; not the ultimate turning point |

| Comparison to Other Targets | Less direct advantage than Caucasus or Moscow; siege was difficult; symbolic over strategic |

To summarize key points:

- Stalingrad’s name made it a symbolically charged target for Hitler and the Nazis.

- The city was vital for Soviet transport and supply lines on the Volga.

- Its capture promised access to rich Soviet oil fields and agricultural resources.

- Operationally, the battle drained German armored strength in costly urban warfare.

- While not the ultimate turning point, it marked a critical moment of German overreach and Soviet resilience.

- Its strategic value lay not just in resources but also in morale and broader operational context on the Eastern Front.

What was the Strategic Importance of Stalingrad during WWII?

At its core, the strategic importance of Stalingrad during WWII was more *ideological* and *symbolic* than purely military or economic. Sure, the city had practical significance as a transport hub near vital oil fields and along the Volga River, but how it shaped morale and perception on both sides was massive. Let’s dive into why Stalingrad was not just a dot on the map but a fiery beacon of hope, obsession, and tactical blunders.

Hitler didn’t pick Stalingrad randomly. The name itself—Stalingrad, or “Stalin’s City”—was a psychological target. Imagine the scene: a city named after the Soviet leader himself. Hitler believed capturing or razing it would deliver a brutal punch right to Soviet morale. It was like swiping a plate from someone’s hand during dinner—and in war, morale often steers the outcome as much as bullets and bombs.

Hitler’s fixation on Stalingrad almost feels personal. He viewed its capture as a direct insult to Stalin, a trophy that would demoralize the Red Army while boosting German soldiers’ spirits. This obsession made him funnel an excessive amount of resources into taking the city, even when wiser commanders might have pushed past, heading toward the richer, more strategic oil fields in the Caucasus.

Think about it: Hitler’s infatuation with the city’s symbolic value ended up dictating military decisions more than strategic logic. The 6th Army, one of Germany’s most powerful forces, became trapped and destroyed partly because of this fixation.

The Military and Tactical Picture: Why the Battle Was a Mess

Strategically speaking, Stalingrad’s military importance was one of control—over the Volga River traffic and protecting the flank of the advancing German Army Group South. But here’s the kicker: the German Army excelled at blitzkrieg—fast, armored, fluid warfare. Urban fighting? Not their favorite cup of tea.

When the battle shifted to the city’s streets, the Germans lost their maneuver advantage. Close-quarter combat in ruined buildings favored the Soviet defenders. Hitler’s insistence on taking Stalingrad turned what could have been a calculated encirclement into a grinding war of attrition, one where the Germans were outmatched.

Attempts to besiege the city were impossible. The Soviets had five armies on both flanks, ensuring the Germans couldn’t cross the Volga to fully encircle the defenders. Meanwhile, the stretched German lines became vulnerable, culminating in the disastrous encirclement of the German 6th Army. This army’s destruction was a huge blow, but it wasn’t the heaviest human loss of the war, nor the final nail in Germany’s coffin.

Geographic and Economic Stakes: Oil and Grain, But Not the Whole Story

Beyond symbolism and combat mechanics, Stalingrad bordered the oil-rich Caucasus region. For Germany, oil was life—fuel for tanks, planes, and vehicles. Capturing the Caucasus oil fields would have been a major prize. Baku, near the Caucasus, was the world’s largest oil production center at the time, and seizing it could cripple the Soviet war machine.

Moreover, controlling Stalingrad would cut off vital Soviet grain supplies and secure transport routes. The city was also a crucial railroad and industrial hub, which made it valuable. Still, these aspects were secondary to the ideological and morale-driven motivations.

In short, Stalingrad was the gateway—not the final prize—to the resources Germany desperately needed. Ironically, Hitler’s refusal to bypass the city delayed the southern advance and disrupted plans to capture those critical oil fields. Sacrificing the tactical initiative over symbolic gains proved costly.

Broader War Context: Where Stalingrad Fits in the Puzzle

Many see Stalingrad as the war’s turning point. But historical records suggest otherwise. By late 1941, the Germans had already lost the chance for outright victory in the East. Stalingrad’s defeat was massive but not decisive in itself. It was an adjunct to the major, later battles like Kursk, which truly decided the Eastern Front’s fate six months later.

The battle of Stalingrad was, in 1942, about survival for Germany. Army Group South hoped to crush the Red Army and secure resources to sustain their campaign. Instead, the battle sucked in men and matériel in a bear hug that Germany could not escape. The loss of the 6th Army marked the beginning of a relentless Soviet push westward.

Comparing Stalingrad to Other Targets: Why Not Moscow or Elsewhere?

You might ask, why not push for Moscow, the Soviet political and manufacturing center? Or simply surround and starve Stalingrad instead of fighting house to house? Well, that’s another twist.

Napoleon took Moscow and lost the war—much to Hitler’s knowledge. Moscow’s capture certainly might have disrupted Soviet arms production, but the Russians had shown they didn’t surrender at such losses. As for starvation tactics, besieging Stalingrad was impossible given the Soviet armies around it and control of the Volga River by the Red Army.

Hitler’s decision to try to capture Stalingrad instead of bypassing it (to protect his flank and push toward the Caucasus) was a gamble fueled more by ego and symbolism than battlefield pragmatism. His obsession led to overwhelming resource allocation to a target with little direct benefit.

Why Does Stalingrad Still Matter Today?

Stalingrad’s strategic importance reminds us war isn’t just logistics and economics. Ideology, morale, ego, and symbolism shape decisions as much as oil fields and railroads. The city became the ultimate symbol of German overreach and Soviet resilience. Its fall lifted Soviet morale and discredited the myth of Wehrmacht invincibility.

For students, history buffs, and even strategists, Stalingrad offers a cautionary tale: never underestimate the power of psychological warfare and symbolism. And never let personal obsession cloud strategic judgment—unless you’re ready for a *very* costly lesson.

Final Thoughts: Lessons from Stalingrad

- Hitler’s obsession turned a tactical distraction into a strategic nightmare.

- Urban warfare negated German strengths, contributing to their defeat.

- The city’s symbolic value had a disproportionate impact on the battle’s priority.

- Strategically, bypassing Stalingrad to secure the Caucasus oil fields could have been wiser.

- Stalingrad was more a symbol of German hubris and Soviet determination than a purely military target.

So next time you wonder about strategic targets in war, remember Stalingrad: some cities hold the weight of names, stories, and hopes that can change the course of history. Sometimes, the battle won inside minds is just as tough as the one fought with bullets.

Why was Stalingrad targeted for its symbolic meaning during WWII?

Stalingrad bore Stalin’s name, making it a symbolic prize. Hitler saw capturing it as a blow to Soviet morale. Destroying the city was meant to humiliate the Red Army and boost German spirits.

How did Stalingrad’s geography affect the German military strategy?

The urban environment nullified German strengths in maneuver warfare. Its location on the Volga River made it hard to besiege. The Germans had to commit large resources, losing flexibility and momentum.

What economic advantages did capturing Stalingrad offer to Germany?

The city was a hub for railroads and industry. Controlling it would aid access to southern oil fields in the Caucasus, which were critical for Germany’s fuel needs. It also threatened Soviet grain supplies.

Was Stalingrad the turning point of the Eastern Front?

No. It was significant but not decisive on its own. The larger turning point came later at Kursk. Stalingrad marked a moment of German survival rather than full strategic defeat.

Why didn’t the Germans prioritize Moscow over Stalingrad?

Moscow was important but harder to capture quickly. Hitler’s fixation on Stalingrad was ideological. Bypassing it toward oil fields might have been wiser, yet Hitler insisted on taking the city itself.