Evidence does not conclusively establish race as the sole or primary motivating factor in Reagan’s War on Drugs, though its policies produced stark racial disparities. The War on Drugs emerged amid rising crime rates and drug epidemics in the 1970s and 1980s, supported broadly across multiple communities. While some lawmakers and voters acted with racial animus, many supported harsh drug laws pragmatically—to address violence and addiction ravaging their neighborhoods.

The Anti-Drug Abuse Act of 1986 exemplifies this complexity. It introduced mandatory minimum sentencing and established a 100:1 disparity in penalties between crack cocaine and powder cocaine possession. Crack was more common in Black communities; powder cocaine more prevalent among white users. This disparity led to a dramatic increase in Black incarceration rates—from 50 to 250 per 10,000 federally incarcerated—and a jump in sentencing disparity from 11% to 49%.

However, the law itself was facially race-neutral. It did not explicitly target any racial group. Instead, systemic and enforcement biases produced disproportionate outcomes. White individuals were less likely to be stopped, searched, or charged compared to Black individuals, despite data showing similar or higher rates of contraband among whites. This reflects how ostensibly neutral laws can create unequal effects in practice when applied within a biased system.

Another important aspect is the support for these policies within Black communities during that period. For example, Washington D.C., a majority-Black city with political autonomy, initially backed increased policing and harsher sentences in the 1970s. Polling and voting patterns show that many Black voters favored anti-drug legislation in the 1980s and 1990s, motivated by fears of drug-related violence and harm to their neighborhoods. The 1994 Violent Crime Control and Law Enforcement Act even enjoyed higher support among Black voters than white voters.

Some Black leaders viewed crack cocaine as a profound threat to their communities. James Forman’s research highlights that Black political figures likened crack to deep social evils. Congressional Black Caucus votes on tough drug laws were split; many favored stricter sentencing to combat crime despite concerns over fairness. This layered internal support complicates attributions of purely racial motivations to the War on Drugs policies.

Historical and political contexts further support a multifaceted view. The War on Drugs occurred amid a nationwide spike in crime rates that pressured politicians across the spectrum to act decisively. Many voters and lawmakers sought pragmatic solutions after prior treatment-focused approaches appeared insufficient. This led to a coalition of supporters including Black political figures, centrist policymakers, and, regrettably, politicians with explicit racial biases like Jesse Helms and Strom Thurmond. Thus, racial animus coexisted alongside non-racial crime-control motives.

“In many cases, voters as well as politicians felt that focusing on treatment hadn’t worked, leading to support for harsher sentencing and a shift towards incarceration and interdiction.” — Historical Analysis

Summarizing the evidence, the War on Drugs under Reagan cannot be reduced to a single motive or actor. It originated from genuine public and political concern over drug epidemics and crime surges. The resulting policies had racially disproportionate impacts due to systemic biases and enforcement differences rather than explicit racial targeting alone. The dilemma shows the difference between law’s intent and law’s effect in a society with ingrained inequalities.

| Aspect | Notes |

|---|---|

| Law Intent | Facially race-neutral; aimed at curbing drug abuse and crime |

| Enforcement Impact | Disproportionately affected Black communities due to systemic biases |

| Sentencing Disparity | 100:1 ratio for crack vs. powder cocaine led to racial incarceration gaps |

| Community Support | Many Black voters and leaders supported harsh laws over drug violence concerns |

| Political Context | Broad bipartisan support driven by crime spike and public pressure |

- Reagan’s War on Drugs policies had deeply racialized consequences but weren’t driven solely by racial animus.

- Facially neutral laws produced racially disparate enforcement and incarceration.

- Black communities often supported harsher drug laws fearing crime and drug harm.

- Widespread crime waves fueled bipartisan demand for stronger drug policies.

- Racial bias existed alongside pragmatic and political considerations in shaping these policies.

Is Race a Motivating Factor in Reagan’s War on Drugs? Diving Deep into the Evidence

So, was race a motivating factor in Reagan’s War on Drugs? The short and intriguing answer is: not exactly as popularly portrayed. Now, before you raise an eyebrow or two, hear me out. This is a complicated story, weaving through politics, communities, law enforcement, and unintended consequences more than clear-cut racial targeting. Let’s tread carefully down this historical rabbit hole together.

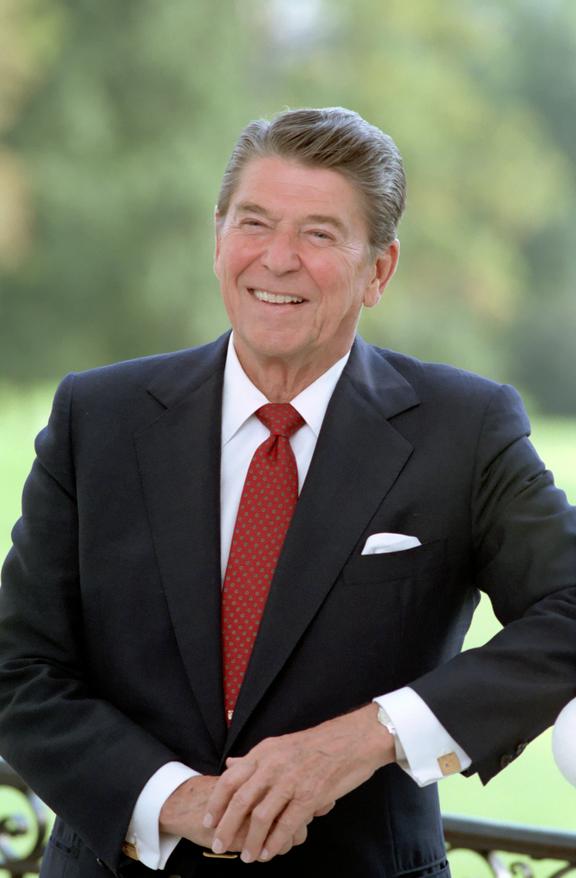

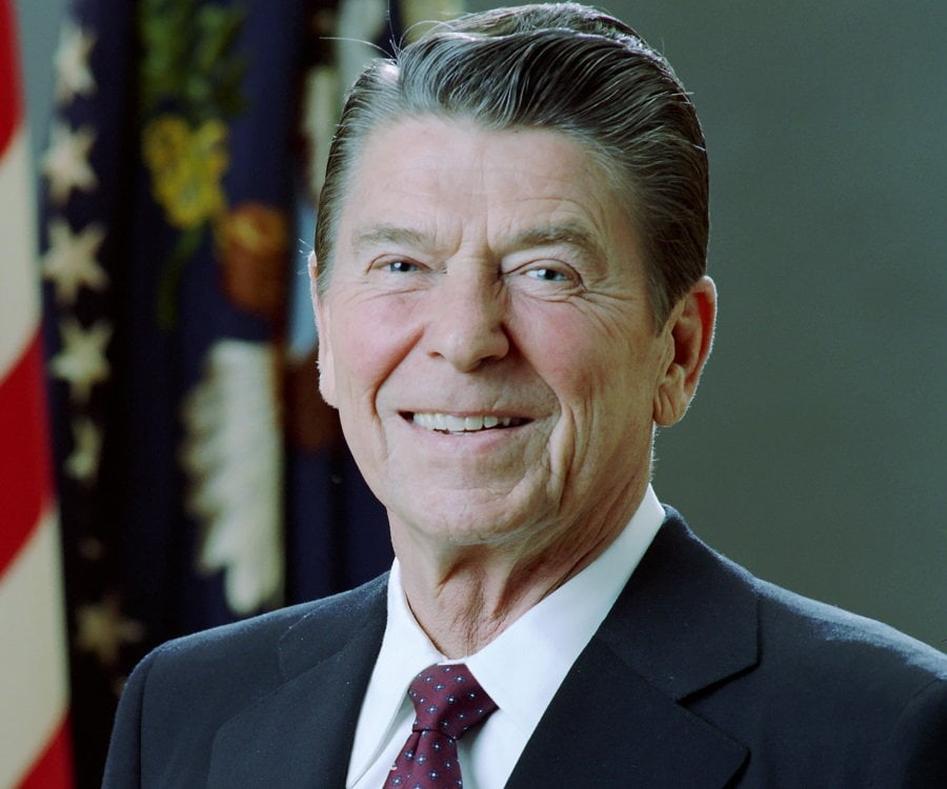

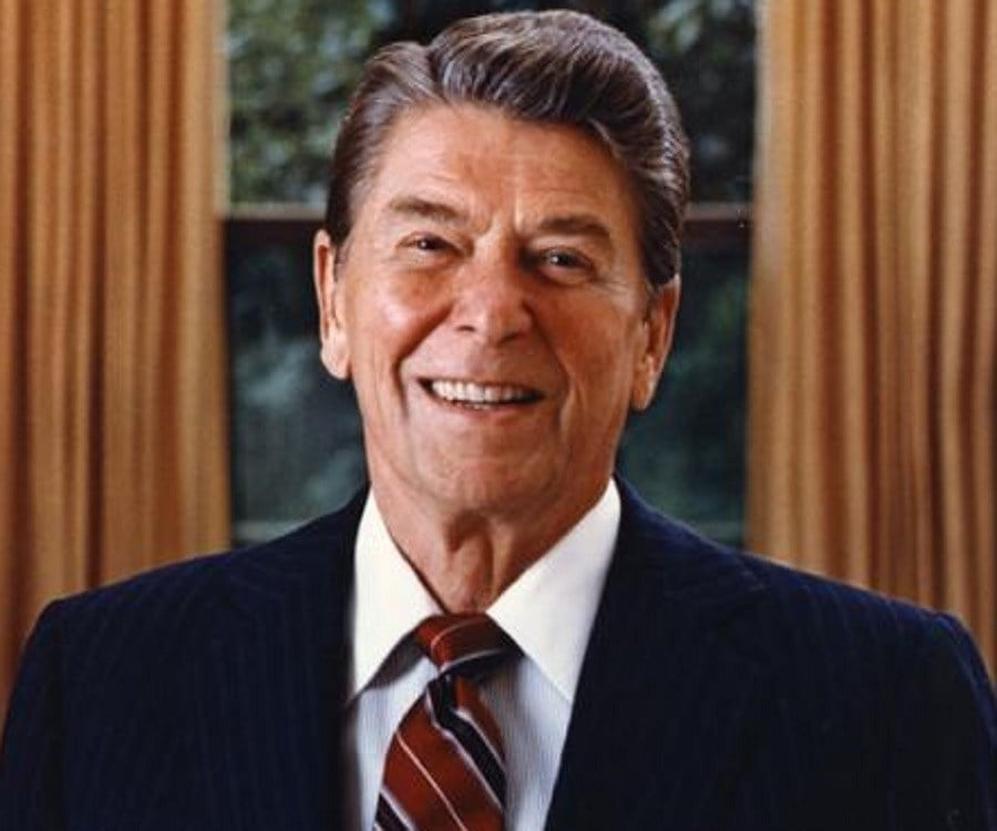

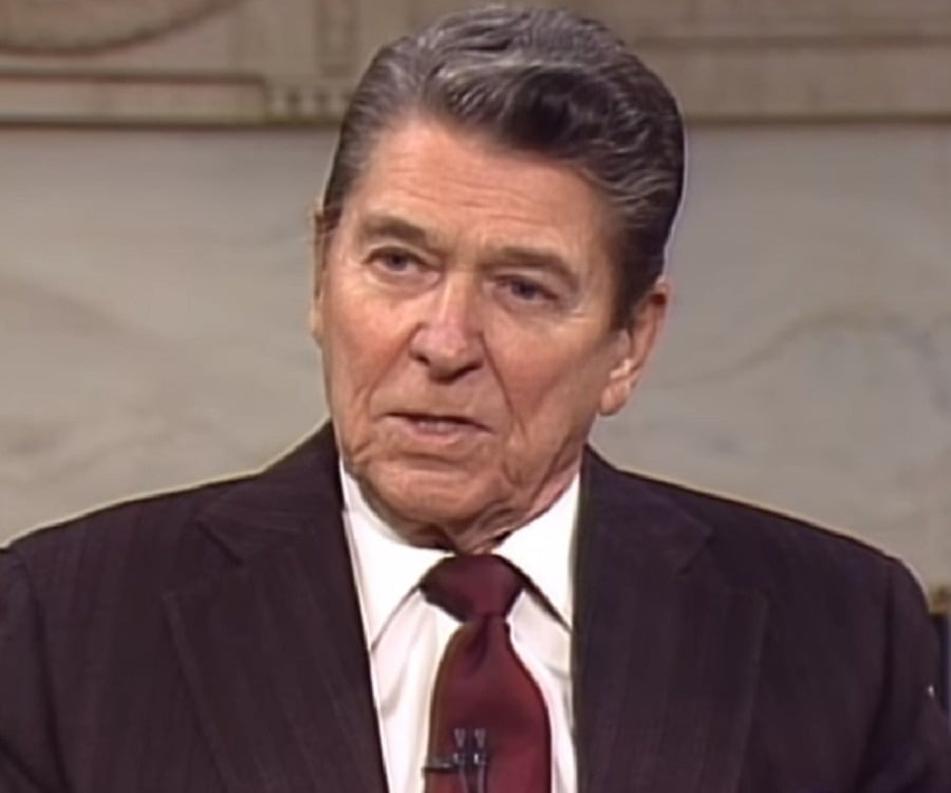

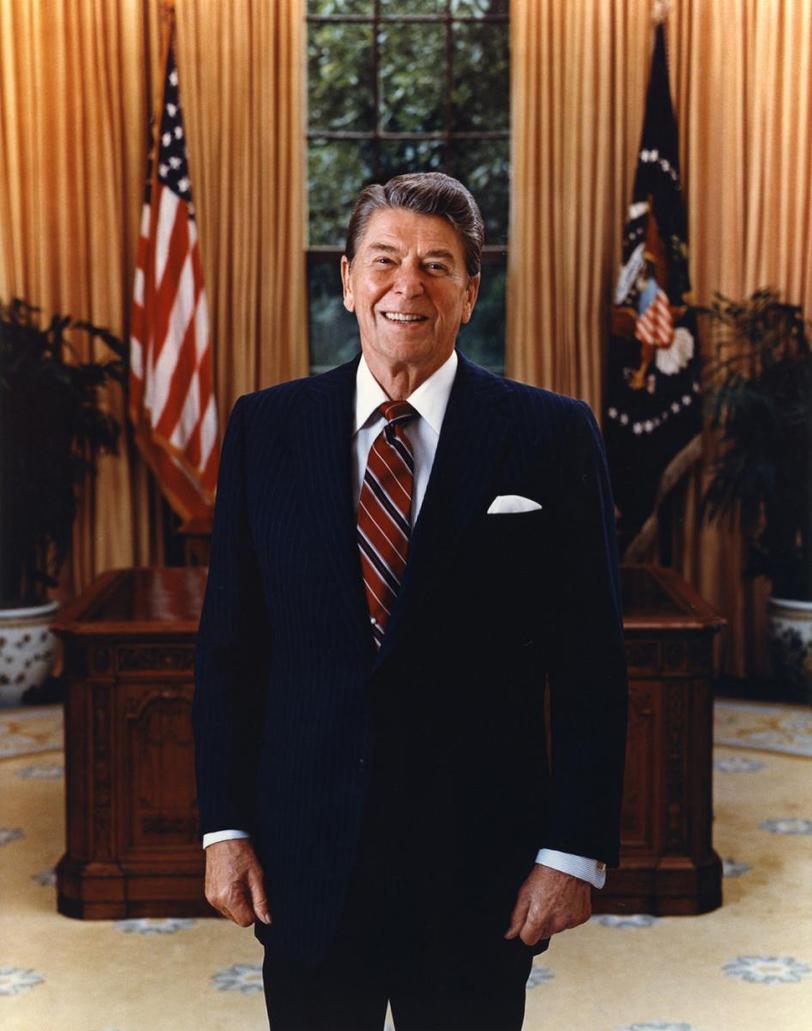

Picture the 1980s: soaring crime rates, cocaine epidemics, and public panic about drugs. President Ronald Reagan steps up with a tough-on-crime approach, culminating in the 1986 Anti-Drug Abuse Act. But was race the main engine? It’s tempting to say yes — those infamous policies disproportionately impacted Black Americans. Still, the reality is more tangled than that.

The Paradox: Black Communities Supported Tougher Drug Laws

First off, there’s an irony many don’t expect: many Black communities initially supported harsher drug laws. Take Washington DC in the 1970s. This majority-Black city council defeated a bill to decriminalize marijuana and instead endorsed stricter penalties on drug dealers and violent offenders. If race were the sole factor, why would these communities push for more policing?

Historian James Forman’s book Locking Up Our Own walks us through this evolution. Black residents feared drug-related violence more than police intrusion back then. It wasn’t blind submission to a racist agenda, but pragmatism in the face of real dangers. In fact, many Black voters and leaders later supported the 1994 Crime Bill, with figures like Rep. James Clyburn explaining that crack cocaine was seen as a community scourge that had to be tackled.

Multiple Forces Built the War on Drugs, Not Just Reagan’s Hand

Media and public hysteria about crime in the ‘70s through ‘90s created a perfect storm. It wasn’t only Reagan; many politicians, interest groups, and communities pressed for action. Crime rates were escalating, so there was strong popular demand to “do something.” Often, policymakers felt treatment-focused efforts had failed. This led to bipartisan support for stricter sentencing and incarceration, not just from racially prejudiced quarters.

Facially Neutral Laws, But Racially Disparate Outcomes

Here is where things get tricky. The laws themselves, such as the War on Drugs provisions or the notorious Anti-Drug Abuse Act of 1986, didn’t explicitly mention race. They were written in language neutral on its face. But these laws ended up hitting Black Americans far harder.

Why? Because the enforcement wasn’t neutral. For instance, the 100:1 sentencing disparity meant just 5 grams of crack cocaine (more common in Black communities) triggered a five-year sentence, whereas it took 500 grams of powder cocaine (associated more with white users) for the same penalty. This disparity exploded Black federal prison populations, while white populations saw much smaller increases.

Michelle Alexander’s book The New Jim Crow famously highlights this: policies can be neutral on paper but still produce racialized outcomes if the system is biased. Think of New York City’s “Stop and Frisk.” Officially nondiscriminatory yet disproportionately targeting Black and Latino individuals despite similar rates of carrying contraband among whites.

The Data: Between Theory and Reality

We should note that at the time, detailed data proving racial intent or discrimination was murky. Many believed the laws targeted drugs, not people. In practice, however, white people were less likely to be stopped, charged, or sentenced harshly, and less likely to use crack cocaine. So, the system operated with racial disparities—whether intended or not.

Complex Support: Crime, Community Safety, and Politics

Many in Black communities supported harsh anti-drug laws because violent drug-related crime tore through their neighborhoods. Polling from the era reflected that fear of the drug epidemic outweighed fears of police overreach. Some Black political leaders pushed for bipartisan crime control measures, emphasizing safety first. Baltimore’s mayor Kurt Schmoke told Congress in 1994 that strong legislation had to receive bipartisan backing because of its community importance.

So, while racist actors like Jesse Helms and Strom Thurmond indeed backed these bills, the support base was broader and more nuanced. There were also pragmatic actors focused on crime prevention, not just racially motivated agendas.

What Does This Mean for Understanding Reagan’s War on Drugs?

It’s tempting to see the War on Drugs as a villainous plot explicitly crafted to target Black Americans. But a closer examination reveals a more complex reality:

- Lawmakers responded to rising crime and public demand. The era witnessed growing drug violence that hurt all communities, including Black neighborhoods desperately seeking relief.

- Laws were drafted as racially neutral but were enforced in racially biased ways. Systemic inequities shaped the outcomes, not explicit racial instructions in the legislation.

- Black communities sometimes supported harsher laws as a strategy to combat drug violence. The goal was security and protection, even if the methods later had devastating consequences.

- Bipartisan politics ensured that various interests, from racists to pragmatists, drove the War on Drugs. No single person or group holds full responsibility for the complex policy outcomes.

Lessons and Recommendations Moving Forward

Understanding the history means grappling with the fact that intent differs from impact. The War on Drugs shows how policies—even with no explicit racial intent—can result in deep racial injustice. It’s a cautionary tale for crafting future laws and enforcement mechanisms.

If we want to avoid repeating past mistakes, we need to:

- Demand transparency and data collection on policing and sentencing by race to catch disparities early.

- Support targeted community-based solutions that address drug addiction and violence without adding layers of incarceration.

- Engage impacted communities in policy design, reflecting their priorities for safety and justice.

- Acknowledge the legacy of systemic biases and seek reform rather than merely tougher laws.

The shockwaves from Reagan’s drug policies remind us that “neutral” language alone can’t stop systemic injustice. Enforcement, societal context, and power dynamics shape outcomes just as fiercely.

Let’s Talk

Have you ever wondered why some laws feel fair on paper but unfair in life? Why do we call something racial discrimination when it’s “just the way things work”? The War on Drugs offers fertile ground for these questions. Its history shines a light on how complicated motives and outcomes can be.

What’s your take? Was the War on Drugs racist by design or a tragic byproduct of ignorance and urgency? Drop your thoughts and let’s unpack history’s lessons together.