The British lost the American War of Independence largely due to internal blame and leadership conflicts, as recorded by British leaders in the 18th and 19th centuries. High-ranking officials attributed defeat to incompetence across political and military ranks, with no agreed cause or responsible party emerging.

British leaders in the period following the war experienced intense disagreements about the causes of the loss. Those who had opposed the war pointed fingers at the government ministry. The army blamed the navy, and the navy countered by blaming politicians. This cycle of accountability avoidance prevented a unified analysis and resolution. Instead, officials shared portions of the blame and aimed to continue their careers despite the setback.

A major point of contention was between the top British generals in North America, Sir Henry Clinton and Lord Charles Cornwallis. Their post-war writings reveal how personal and professional rivalries shaped the British interpretation of defeat. Both men issued official letters and reports immediately after Yorktown, the decisive battle in 1781, to explain failures.

At first, Clinton blamed the navy for delays in reinforcements, insisting that without timely naval support, the army’s position worsened. Cornwallis’s report suggested, though cautiously and politely in line with 18th-century decorum, that he had stayed at Yorktown because Clinton ordered him to, despite his preference to regroup elsewhere. This version irritated Clinton. He felt his leadership was unfairly questioned.

Correspondence between Clinton and Cornwallis revealed tensions. Cornwallis excused himself for the ambiguous wording due to fatigue, but the damage was done. News of the dispute became public, and Clinton believed his reputation suffered. The reception they received upon returning to England intensified the rivalry. Cornwallis was welcomed warmly, while Clinton encountered cold shoulders.

Clinton responded with a pamphlet refuting Cornwallis’s account. In this document, Clinton squarely blamed Cornwallis. He argued Cornwallis disobeyed orders and marched into vulnerable territory in Virginia, which doomed the campaign. According to Clinton, if Cornwallis had remained in the Carolinas, where he was meant to hold position, the defeat might have been avoided. Notably, Clinton no longer blamed the navy in this version, focusing all fault on Cornwallis.

Scholars note potential political motives behind this shift. The British navy had redeemed its public image with a decisive victory over the French in 1782. Clinton likely avoided blaming naval commanders like Admiral Rodney to prevent alienating a popular institution and causing a public backlash.

Beyond individual disputes, British leaders engaged in widespread mutual recriminations. Each aimed to deflect responsibility to competitors in government, army, or navy. This political infighting affected morale and strategic unity. No consensus arose on why Britain lost. Instead, the necessity of assigning blame became a key survival tactic for careers and reputations.

British reflections show that even successful military commanders often handle defeat by pointing fingers. Blame became a recognized, if destructive, skill in leadership. The post-war acrimony shaped contemporary accounts and influenced historical narratives for decades. It demonstrated the difficulty of finding a clear cause in complex wars.

- British leaders blamed each other’s incompetence for the American defeat.

- Disputes between Clinton and Cornwallis highlight personal and military tensions.

- Clinton initially blamed the navy, later fully blamed Cornwallis in a pamphlet.

- Political considerations shaped who was publicly blamed, especially regarding the navy.

- No single cause or individual was agreed upon; mutual blame was widespread.

Why did the British lose the American War of Independence, according to the British in the 18th and 19th century?

The British lost the American War of Independence due to a tangled web of blame, mismanagement, and political squabbling, chiefly marked by incompetent leadership and failed cooperation between the army, navy, and government. Let’s unpack how 18th and 19th-century British insiders explained their stunning defeat.

From the perspective of British leaders back then, the story isn’t neat or heroic. Instead, it’s a messy saga where blame gets tossed like an unloaded cannonball — everyone firing off accusations but none willing to own up to defeat. Humor aside, it was a major political and military headache.

Right after the war ended, high-ranking officials debated fiercely about who bungled the most. Soldiers blamed sailors, sailors blamed politicians, and politicians blamed everyone else. The ministry, army, and navy were like siblings fighting over who left the front door unlocked while the house burned.

The Great Blame Game: No Clear Villain

One glaring problem was the lack of consensus. British elites could not agree on a single cause for their loss. Instead, the defeat became a shared embarrassment. Ministers pointed fingers at the military; generals grumbled about lack of support; admirals grumbled about politics. The result? No unified understanding or narrative.

This uncertainty about fault was more than academic—it affected careers and reputations. Many blamed others to salvage their own futures, advancing their narratives carefully, just like politicians at a modern press conference dodging tough questions.

Clinton vs. Cornwallis: The Army’s Public Feud

The tension boiled over into what historians call the Clinton-Cornwallis controversy, arguably the most dramatic post-mortem of the war within the British ranks. These were the two senior British generals in North America, and their disagreement shaped much of how blame was officially assigned.

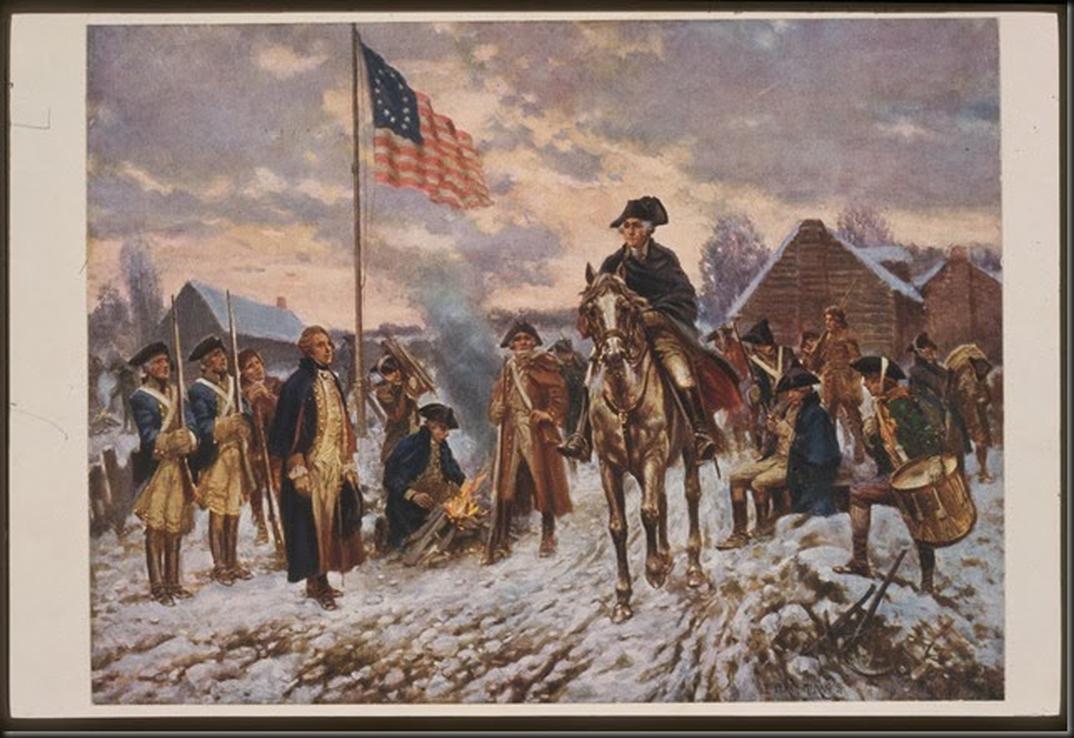

After the defeat at Yorktown—a decisive American victory—each wrote reports spinning the causes through their personal lenses. Sir Henry Clinton, the commander in chief, initially lashed out at the navy for slow reinforcements. He believed that timely naval support might have saved the day.

But Lord Charles Cornwallis, who surrendered at Yorktown, released his own official account suggesting, politely but pointedly, he was stuck in a losing position due to Clinton’s orders and empty promises of help. Cornwallis implied he would have preferred to withdraw but was overruled. This was gentlemanly indirectness, yet the implication was clear: Clinton’s mismanagement contributed to the defeat.

Clinton did not take this lightly. He demanded explanations, claiming his reputation was unfairly tarnished. Cornwallis responded vaguely, citing fatigue and haste in writing, but the damage was done. Public perception mattered. When Cornwallis returned to England, he received a warm welcome, while Clinton felt sidelined and cold-shouldered. The snub only sharpened their rivalry.

The Pamphlet Wars: Blame Goes Public

Refusing to be outdone, Clinton penned a pamphlet to respond, firmly shifting all blame onto Cornwallis. This pamphlet was a bombshell—a mix of official letters and sharp accusations alleging Cornwallis disobeyed orders and entered Virginia recklessly. Clinton argued that Cornwallis’s decision to stay in Virginia rather than the Carolinas led directly to the disaster at Yorktown.

It’s important to note this pamphlet avoided blaming the navy. Why? By 1782, after smashing the French fleet, the British navy enjoyed renewed public glory. Blaming Admiral Rodney, a national hero, might have backfired politically. Clinton was savvy enough to pick his targets carefully.

Political Motivations: Politics in the Midst of War

Beyond military failure, the blame shifting served political ends. Public support for the navy was crucial. Shifting too much blame there could provoke national outrage. The pamphlet and letters were as much about protecting reputations and future careers as they were about history.

Basically, high-level British leaders weren’t just researchers of failure—they were also politicians and survivors. Their writings reveal more about self-preservation than honest analysis. This layer of political calculation muddies the waters of understanding the war’s actual causes.

The Bigger Picture: Why Blame Was Inevitable

Let’s be clear: war rarely has simple winners and losers, nor does defeat have a single cause. Historians sometimes romanticize clear-cut victories or disasters. The British experience after losing the American colonies fits a common military phenomenon—leaders dissect failures, looking for scapegoats.

So why did the British lose? It wasn’t one person or one mistake. It was a combination of poor coordination between the navy and army, indecisive or contradictory orders, political pressures, and competing egos. No one wanted to say, “I messed up,” publicly.

After Yorktown, acrimony among British leaders only increased, making it harder to find collective responsibility or learn from mistakes. Clinton blaming Cornwallis, Cornwallis hinting at Clinton’s errors, the politicians dodging accountability—all this adds up to a failure not just of the battlefield, but of leadership and institutional unity.

What Modern Leaders Can Learn

This story provides a cautionary tale. Effective leadership demands clear communication and shared purpose. When different branches of command or government feud publicly, it weakens the entire effort.

If we zoom out, British contemporaries put forward a detailed, human picture of loss. It’s not about grand strategy alone—it’s about how people defensively protect themselves in times of failure, sometimes fueling confusion rather than clarity.

Imagine modern conflicts where generals, admirals, and politicians trade blame instead of strategy—and you see how similar patterns repeat. The British defeat in America reminds us to watch for acrimony that clouds judgment, often as destructively as the enemy.

In Conclusion

The British explain their defeat by pointing fingers at each other, highlighting incompetent military leadership, conflicting orders, and political manipulation. The lack of unified command between the army and navy, combined with the infamous Clinton-Cornwallis feud, spelled disaster. The British lost not just the war, but the battle to assign blame, clouding the path to understanding.

Next time you hear about the British losing the American War of Independence, remember it wasn’t a single failure—it was a cocktail of mistakes, rivalries, and blaming games, all mixed in the bubbling cauldron of 18th-century politics and military mishaps.