To become a historian, the standard path involves earning advanced degrees in history and developing specialized research skills. Typically, one starts by obtaining a Bachelor’s degree (BA) in history or a related field. Following this, pursuing graduate studies—most commonly a Master’s (MA) and then a Doctorate (PhD)—is key, especially for academic and high-level professional positions. This educational foundation teaches individuals to think critically about history, analyze sources, and produce original research, distinguishing professional historians from enthusiasts.

In the United States, many professional historians have BA, MA, and PhD degrees in history. Sometimes, people study other disciplines like sociology or philosophy in undergraduate programs and later shift to history for graduate studies. Some institutions have trimmed or eliminated the MA, resulting in students who directly obtain a PhD after their BA.

Graduate education in history is crucial for advanced careers. For academic roles such as college professors, a PhD is generally required. Positions in libraries, museums, or archives often need specialized graduate degrees alongside content expertise—like a Master of Library and Information Science (MLIS) for librarianship.

While some jobs require only an undergraduate history degree, these are more common in private sector or government jobs, such as those in national parks. Teaching history in primary or secondary schools might require different credentials, often state certifications, and varies based on educational levels and locations.

The graduate experience is designed not merely to convey facts but to cultivate a historian’s mindset. Historians approach history through questions and interpretative arguments rather than just memorizing dates and names. They engage deeply with historiography—studying how interpretations and approaches to historical topics change over time. This methodological training is essential for producing original research that adds new insights to historical knowledge.

Research is central to becoming a historian. Graduate students conduct original archival research, starting with focused questions that guide their choice of sources—ranging from official sermons to personal narratives to novels, depending on the topic. Research often expands with follow-up questions. For those aiming to earn a PhD, this research culminates in a dissertation providing fresh perspectives on historical subjects.

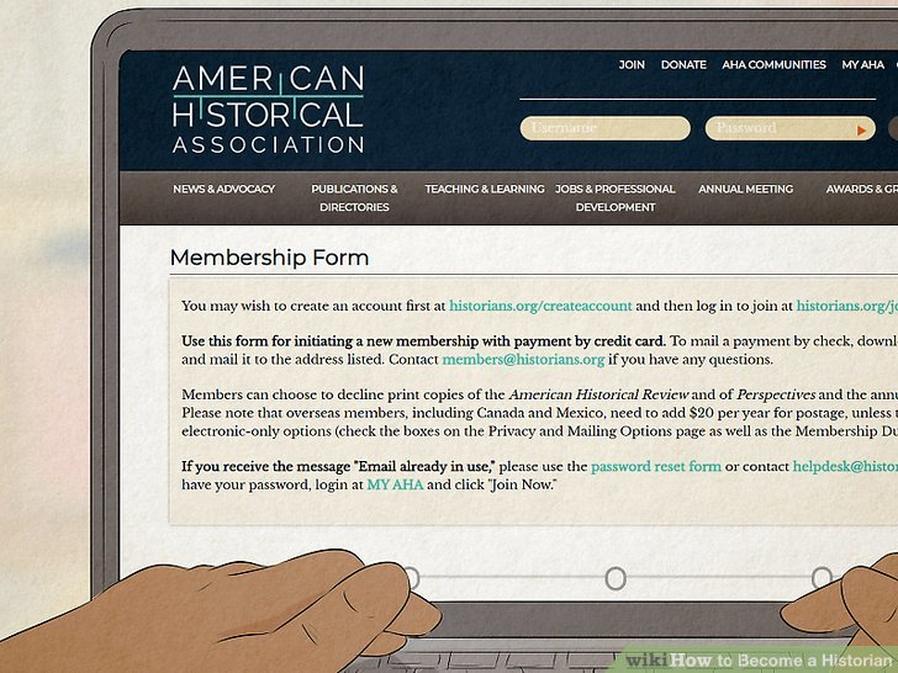

Professional development for historians includes presenting research at academic conferences and publishing in peer-reviewed journals. Successful historians gradually produce scholarly articles and books that contribute to and reshape understanding in their fields. Publishing demands affiliation with academic institutions, and scholars invest years refining their dissertations into publishable works.

Career progression in academia usually involves:

- Obtaining a doctoral degree.

- Securing postdoctoral or teaching positions at universities, which are increasingly competitive.

- Gaining institutional support to access archives and conduct research.

However, the academic job market has become challenging. The traditional tenure-track career path is shrinking. Many new teaching roles are adjunct or temporary. There are far more history PhDs than tenure-track openings. Consequently, many graduates face unstable employment and low pay.

Non-academic history careers in museums, archives, and libraries also grow more competitive due to the surplus of qualified candidates. The opportunity cost of time spent obtaining advanced degrees is significant. The financial and career uncertainties are considerable, especially in recent years.

Despite challenges, many individuals engage in historical research without formal credentials. Public archives and libraries are accessible, allowing anyone passionate to explore history deeply. Graduate programs are valuable chiefly because they teach how to think, analyze, and produce scholarly work rather than for mere access to sources.

Those considering history as a career should carefully weigh the viability. Pursuing graduate degrees remains essential for academic and specialized museum or archival careers. Yet, realistic assessments of job prospects and financial implications are critical.

| Step | Details | Career Impact |

|---|---|---|

| Undergraduate Degree | BA in history or related discipline | Basic foundation; eligible for some entry-level jobs |

| Graduate Degree | MA and/or PhD in history; specialized training | Required for college teaching and research jobs |

| Research & Publication | Archival research, historiographical essays, peer-reviewed articles | Builds academic credibility and career advancement |

| Academic Positions | Postdoctoral roles, tenure-track jobs (scarce) | Long-term career stability (if attained) |

| Non-academic Roles | Librarians, archivists, museum professionals with niche degrees | Alternative paths but competitive and limited |

Many aspiring historians share a passion for uncovering the past. They can pursue independent research without formal credentials, using public archival resources. Graduate training primarily instills analytical thinking, interpretation, and rigorous research skills unlike general historical inquiry.

- Becoming a professional historian usually requires BA, then graduate degrees (MA, PhD).

- Graduate school teaches critical thinking, methodical research, and historiography.

- A PhD is necessary for college teaching and most research careers.

- Academic jobs are very competitive and decreasing in availability.

- Non-academic roles require specialized degrees but are also limited.

- Anyone can engage with history by accessing public archives and libraries.

- Careful consideration of career viability is advised before committing to graduate education.

How Exactly Do You Become a Historian?

To become a professional historian, you generally need to study history extensively, often earning a Bachelor’s degree, progressing to graduate school for a Master’s and, most critically, a Ph.D., which is essential for academic positions. But that’s just scratching the surface of this fascinating journey, so buckle up.

Ever wondered what it truly takes to earn the historian badge? Spoiler alert: it’s not just about memorizing dusty old dates or naming all those kings and queens. Becoming a historian means learning to think in layers, ask sharp questions, and dive deep into sources. Let’s unpack all this with a pinch of wit and a splash of reality.

The Usual Route: Schooling and Degrees

Most historians start their expedition at college, majoring in history. But here’s a twist: you don’t always need to study history right away. Some folks first study something else—like sociology or philosophy—and then switch gears to history for their graduate degrees. Pretty neat, right?

In the US, it’s common to see historians holding a BA, an MA, and a Ph.D. In some institutions, they’ve dropped the MA stage altogether, letting students jump from a Bachelor’s straight into a Ph.D. program. Why? Efficiency, mainly. Yet, to snag a college professor job or a high-level research position, a Ph.D. is typically the golden ticket.

History Careers: What’s Needed Where?

Thinking about working in a museum or library? You’ll typically need more than just content know-how—you’ll want specialized training, such as a Master of Library and Information Science (MLIS), which gears you up for archive or librarian roles.

If teaching history tickles your fancy, your qualifications hinge on *where* you want to teach. Want to be a high school history hero? Requirements vary by state; a Bachelor’s plus certification might suffice. But college? That’s a tougher crowd. A Ph.D. is more or less non-negotiable.

Private sector jobs or government gigs, like those in national parks, sometimes accept applicants with only an undergraduate degree. So, history isn’t just about suits and chalkboards — there’s room for diversity in career choices.

Can You Become a Historian Without a Degree? Absolutely.

Here’s something wonderful: anyone can research history. No fancy degree needed to wander archives or sift through primary sources. If you can read, you can play historian.

So why the push for grad school? Because graduate programs teach you to think like a historian. They sculpt your mind to ask probing questions instead of just rattling off facts. Imagine learning to tell a story with evidence, argument, and context—that’s the historian’s superpower.

Thinking Like a Historian: The Graduate School Secret Sauce

Most people think history is a static list of facts—names, dates, battles. Nope. Historians see history as a lively conversation. They explore arguments and questions, even disagreements that aren’t fights but intense intellectual debates.

How is that learned? Graduate students often write historiographical essays. These essays explore how other historians tackled a topic and how interpretations shift as societies change their viewpoints. It’s like peeling an onion of perspectives through time.

Ever heard someone complain about “revisionist history,” accusing others of messing with the truth? Historians see revisionism as natural. Different eras bring fresh questions and new angles on the past. Isn’t that exciting?

Research: The Heartbeat of Being a Historian

Research starts with questions—big or small. Want to know how a certain sermon influenced a community in the 1700s? Or how slavery narratives shaped societal views? Different questions lead to different sources. Novels, letters, speeches, artifacts—you name it.

Each answer uncovers more questions, leading to intriguing research chains. In grad school, a solid paper from this process often blossoms into a dissertation—a full-on, deeply researched document that adds fresh understanding to history’s vast mosaic.

Professional Development: Sharing and Refining Knowledge

Historians never work in a vacuum. They hit conferences, talk shop with peers, present findings, and get feedback. This back-and-forth sharpens ideas. Then, there’s the thrill (or terror) of peer review: submitting papers to journals where other historians judge the work rigorously.

Success here often leads to book deals. But a book isn’t just a data dump; it must reveal new insights, showing how examining those old sermons or diaries changes what we know.

The German Perspective on Career Steps

In places like Germany, becoming a historian involves grabbing a doctoral title first. Then comes the post-doc phase—where you affiliate with a university. This step is competitive; jobs are scarce and often temporary contracts.

If you get that post-doc gig, you gain better archive access and sometimes funding for research travel. It’s a grind, but it’s how you cement yourself in the academic world.

The Sobering Realities: The State of History Careers in 2022 and Beyond

Warning: The traditional historian’s career path (Ph.D., tenure-track job, books, and long-term security) is fading fast. Public universities tight budgets and enrollment drops hit humanities hard. Schools favor STEM over soft skills like history.

Endless Ph.D. production means fierce competition. For every tenure-track gig, there might be three skilled applicants. Adjunct or visiting instructor roles dominate new teaching jobs. Stability? Willpower-tested, at best.

Even jobs in libraries, museums, or archives face a daunting backlog of Ph.D.-qualified applicants. The financial and mental toll of several years in grad school—when you could be earning and building your resume—is an important factor.

One historian’s tale: years of uncertainty, living paycheck-to-paycheck, and luck playing a huge role in finally landing a decent job. And getting tenure? Plan to publish *not one*, but *two* books just to stand a chance. Sounds grueling because it is.

So, Should You Still Become a Historian?

If you’re passionate about history but wary of the academic rat race, you can still deeply explore history without a Ph.D. Visit archives, write blogs, publish independently. Your curiosity can thrive without the years-long grad school gauntlet and bleak job prospects.

It’s a tough pill to swallow if your dream is to be a university professor. But honesty helps you avoid painful surprises.

Curious minds can still uncover truths and tell stories about our past. History isn’t a closed club—it’s an open invitation.

Publishing and Building Your Academic Portfolio

For those who do enter academia, publishing is king. Grad students often start with a few peer-reviewed articles, to prove research chops. The dissertation usually becomes a book or a series of articles after graduation.

Back in the day, that alone could secure an academic job. Nowadays, it takes multiple publications and sometimes years outside school before a tenure-track chance arises. Revision to book form can take years, and juggling that with teaching or adjunct work? It’s a marathon, no question.

Final Thoughts and Recommendations

So, how exactly do you become a historian? It starts with curiosity and a desire to dig into the past. If you want to do it professionally, be prepared for long schooling and fierce competition. Remember, grad school isn’t just classes—it’s training your brain to ask the right questions and make bold interpretations.

If your goal is academic tenure, it requires grit, publications, networking, and a bit of luck. But if you want to explore history on your own terms, archives and libraries welcome you with open arms.

Why not start with a visit to your local archive? Or tackle a small research project and write a blog post about it? You can craft your historian story without a Ph.D., with none of the career rollercoaster drama.

Ultimately, choose the path that feeds your love of history without sacrificing your well-being. Because a historian’s life is about uncovering stories, not surviving stress—that’s priceless.

Additional Reading and Resources

- Want to know more about history careers? Check out the AskHistorians subreddit FAQ for tons of wisdom.

- For a frank discussion on the pitfalls of grad school in history, see this eye-opening post.

- Explore different research methods in history with this detailed guide.

- Wondering what “doing history” truly means? Read this fascinating explanation.

What educational steps are needed to become a professional historian?

Most professional historians earn a BA in history, followed by graduate school. Many complete a master’s and then a PhD. Some skip the master’s and move straight to a PhD. Advanced degrees prepare you for academic roles.

Do you need a PhD to work as a historian outside of academia?

A PhD is often required for college teaching and high-level research jobs. But library, museum, or archive positions usually need a relevant graduate degree, such as an MLIS for librarians. Some government or private roles accept a bachelor’s degree.

Can someone without formal degrees work as a historian?

Yes, anyone can research history, visit archives, and write about it. However, graduate training helps you learn how to think like a historian, analyzing sources and arguments deeply rather than just collecting facts.

How does graduate school teach you to think like a historian?

Graduate programs train you to ask questions and form interpretations. You study how other historians have approached topics and write essays that examine changing methods and viewpoints. This critical thinking distinguishes professional historians.

What does original research involve for a historian?

Historians start with a question and seek out relevant sources like letters or narratives. Their research leads to new questions and deeper investigation. This work often becomes a dissertation or journal article adding to historical knowledge.

What challenges exist in pursuing an academic career in history today?

The traditional path to a stable university job is shrinking. Financial pressures and a shift toward STEM fields reduce humanities roles. Graduate degrees in history may not guarantee secure academic employment anymore.