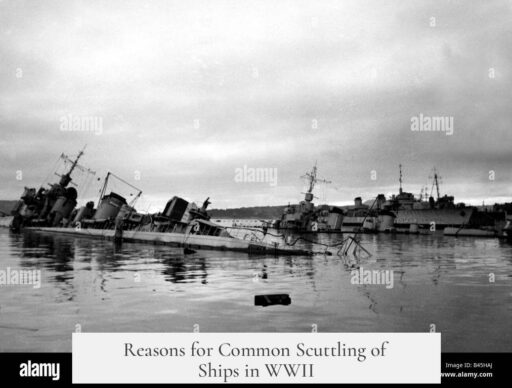

Scuttling ships in World War II was commonly done to prevent enemy forces from capturing valuable intelligence, technology, and vessels. It also served to protect navigational safety during wartime and to uphold naval pride. Practical factors like salvage logistics and the risk of enemy reuse influenced decisions to scuttle rather than attempt recovery.

One of the main reasons for scuttling was the need to protect classified materials. Ships often carried critical codes, machines, and codebooks. The Enigma machine, for example, was a prized asset for both sides. If captured, it could compromise entire naval operations. The Royal Navy’s capture of U-110’s Enigma machine was a rare exception where the Allied side gained important intelligence. Yet, crews frequently destroyed or disposed of these materials separately to keep them from enemy hands. When codebooks or machines were thrown overboard or burned, crews scuttled the ship to prevent the entire vessel and its technology from being captured.

Another reason was to block the enemy from gaining technical intelligence. Captured ships allowed detailed study of enemy design, armament, and technology. This intelligence was vital in the naval duel of engineering and countermeasures. For instance, knowing an enemy submarine’s propulsion or radar system helped develop better detection or evasion tools. U-boat captures yielded insight into torpedo types and hull designs. Therefore, scuttling denied the enemy a treasure trove of technical data that could shift naval advantages.

Naval tradition and pride also played a role. Commanders saw scuttling as a way to deny the enemy the symbolic and strategic victory of taking a ship intact. Having a ship captured was akin to losing a flag in battle. Propaganda benefit from seizing intact enemy vessels was significant, so many captors hid or downplayed their wins. Scuttling ensured the enemy’s tangible trophy never materialized. This was a matter of honor and morale on both sides.

Practical navigation safety was a further reason. Wartime sea lanes were crowded and often traveled under blackout conditions to avoid enemy detection. Damaged or disabled ships that could not be safely recovered risked becoming hazards. Collision posed a serious threat amid wartime chaos. Scuttling a crippled vessel eliminated such hazards, lowering risks for other friendly ships operating nearby.

The historical precedent of ships being captured and reused added urgency to scuttling. In earlier conflicts, such as the Russo-Japanese War, captured capital ships were refurbished and pressed into service against their former owners. The Japanese had salvaged many scuttled ships at Port Arthur, reusing them effectively. WWII commanders knew captured ships could still threaten them if turned around and used by the enemy. Scuttling removed that threat.

Logistical and practical salvage issues influenced scuttling decisions. Even with dedicated fleet tugs, recovering a damaged ship was resource-intensive. Conditions such as enemy naval superiority, proximity of repair facilities, and feasibility of towing played roles. For example, when the US Navy lost the oiler Neosho, salvage was impossible near enemy-controlled waters and without nearby tugs. The cost and risk outweighed potential benefits. Thus, scuttling was often the safest and most practical course.

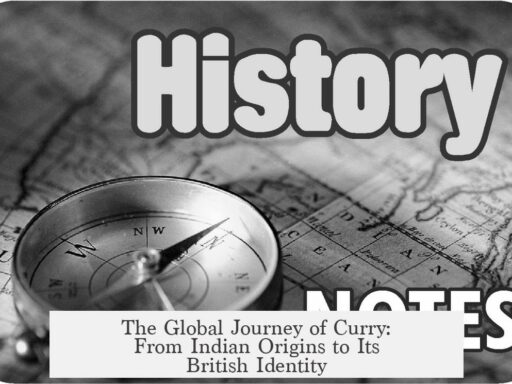

| Reason for Scuttling | Key Details |

|---|---|

| Prevent Enemy Capture of Classified Materials | Destroy Enigma machines, codes, codebooks to block intelligence leaks |

| Denial of Technical Intelligence | Block study of ship design, weapons, radar, and propulsion by enemy |

| Pride and Honor | Prevent enemy propaganda wins and protect commander’s reputation |

| Navigation Safety | Remove hazards in blackout zones to prevent collisions in busy war shipping lanes |

| Historical Risk of Ship Reuse | Stop captured ships from being salvaged and re-armed by enemies |

| Logistical Salvage Constraints | Consider costs, towing feasibility, enemy threat, and repair location |

Scuttling ships during World War II emerged as a multi-faceted tactic. Commanders balanced intelligence security, tactical advantage, navigational safety, and honor. They also accounted for practical realities of salvage challenges and the potential for enemy reuse. This strategy ensured that a defeated or incapacitated ship could not benefit the enemy at sea or on land.

- Preventing enemy capture of codes and machines protected critical intelligence.

- Scuttling denied adversaries detailed technical data and weaponry.

- Commanders valued honor and aimed to avoid propaganda losses.

- Removing navigation hazards safeguarded other ships during blackouts.

- Historical cases showed the risk of enemy reuse of captured ships.

- Logistics and safety often made scuttling the most feasible option.

Why Was Scuttling Ships in WW2 So Commonly Resorted To?

Scuttling ships in WW2 was a widely resorted-to strategy primarily to prevent enemy forces from capturing critical classified materials, deny them technical intelligence, maintain pride among commanders, avoid navigational hazards, stop enemy reuse of captured vessels, and due to practical salvage limitations. These combined factors made scuttling an essential, though somber, tool in naval warfare during that turbulent period.

Now, let’s dive deeper into why so many captains and navies chose to deliberately sink their own ships despite the obvious loss.

Stopping Secrets From Falling Into Enemy Hands

One of the biggest worries was sensitive information—code machines, codebooks, maps, and other classified materials. The infamous Enigma machine, used by German U-boats to encrypt messages, stands out. These devices were priceless treasures in the intelligence war.

There’s a dramatic story of the Royal Navy intercepting the German submarine U-110. They managed to snag the Enigma machine and its codebooks before the sub sank while being towed, a stroke of luck. Contrast that with U-570, which was captured intact but without its code materials, because the German crew tossed them overboard before the boarding. This shows how critical it was to either evacuate or destroy these materials before an enemy’s hands could grab them.

Destroying ships ensured that any overlooked machines or papers couldn’t be casually looted later. Imagine handing your enemy a cheat sheet; naval commanders preferred to destroy the entire classroom instead.

Denial of Technical Intelligence—Keeping Secrets on the Other Side

Naval warfare wasn’t just about guns and torpedoes—it was an intense race for technological advantage. Each side stalked the other, hungry to know exact details of radar systems, propeller designs, hydrophones, and weaponry. Captured enemy vessels gave a treasure trove of intel to reverse-engineer or improve countermeasures.

Torpedoes, sonar equipment, radio gear—these all mattered. Capturing a U-boat meant hours or days of studying its secrets, tweaking one’s own tech to nail the enemy harder next time. In fact, the Cold War decades later echoed this obsession when the US tried to secretly salvage a sunken Soviet submarine to peer into its tech secrets.

So sinking your own ship meant closing that window of opportunity for the enemy, denying them the chance to peek at your playbook. It’s like burning your homework so the class can’t copy it.

Pride, Honor, and the Sting of Losing a Ship Intact

There’s a strong psychological and symbolic layer to the scuttling puzzle. Commanders didn’t take kindly to seeing their beloved ships fall into enemy hands like trophies. Think of it as the naval equivalent of losing your flag or badge. It hurt morale and was a propaganda bonanza for the other side.

In WWII, every captured ship was a morale boost for the enemy and demoralizing for the original owners. So commanders chose to scuttle rather than surrender vessels fully intact. Even capturing sides sometimes hid their success to avoid the opponent knowing “we just got your secrets!”

So, scuttling delivered a blow back to the enemy’s pride while conserving your own honor, even in defeat.

Clearing the Roads — Ensuring Navigational Safety

Scuttling wasn’t just about intelligence or pride. It was practical too. Imagine a crippled ship stranded in a busy channel or shipping lane. Ships in wartime traveled in pitch darkness, without lights, to avoid enemy detection but dramatically increasing collision risks.

A derelict ship blocking this vital passage was a disaster waiting to happen. Other vessels could crash into it, risking multiple losses. So navies would often scuttle damaged capital or merchant ships swiftly—using torpedoes, gunfire, or air attacks—to sink them where they wouldn’t be a hazard.

This pragmatic approach saved lives and ships, at the cost of one already crippled warhorse.

Historical Ghosts—Stopping the Enemy From Recycling Your Ships

Before WWII, it was fairly common for foes to capture enemy warships and press them into their own navies. The Russo-Japanese War of 1905 had examples where battleships like Oryol and Imperator Nikolai I were seized and even reused.

Even scuttled ships weren’t safe, as sometimes enemies salvaged them and returned them to battle. The Japanese famously raised several scuttled ships at Port Arthur and recommissioned them.

By WWII, this memory was fresh. Losing a functioning ship to the enemy—especially one they could repair and refit—was a duel defeat. Hence, commanders preferred to sink or destroy their ships completely rather than risk boosting enemy fleets.

Logistics of Salvage: Sometimes, It’s Just Not Worth It

The practical side of things couldn’t be ignored. Salvaging a damaged ship meant sending fleet tugboats, allocating fuel, risking crews in hostile waters, and hauling the ship long distances for repairs.

For example, the US fleet tug didn’t even bother recovering the Neosho in the tense days before Midway. The Japanese held the naval upper hand then. Tugboats were also often stationed too far back, and a long tow to safe ports like San Francisco could take months.

If the odds were poor and the cost was too high, scuttling was the safer option. No point risking more lives or equipment to save a vessel that might never sail again soon.

Wrapping It Up: More Than Just Sinking a Ship

So, why did scuttling ships in WWII become a frequent, sometimes heartbreaking choice? It boiled down to a nexus of strategic, technical, psychological, and practical reasons.

- Stopping the enemy from getting codes and machines saved crucial intelligence secrets.

- Preventing technical study denied the enemy advancements from your ship’s technology.

- Pride and honor stopped symbolic victories and enemy morale boosts.

- Avoiding navigation hazards kept troop and supply lines safer in tricky blackout conditions.

- Historical memory of enemy reuse made total ship destruction a defense against fleet augmentation by foes.

- Logistical realities of salvage often meant scuttling was the smartest, safest call.

Next time you hear about a battleship or submarine purposely sunk by its own crew, imagine the tough choices behind that decision. It’s a calculated sacrifice, a mix of battlefield art and grim reality.

What would you do if you were a captain ordered to scuttle your vessel? Sinking your own ship to deny your enemy valuable secrets must rank as one of wartime’s toughest calls. Yet, as history proves, it saved countless lives and helped keep strategic balances intact in World War II’s naval battles.

Why was preventing enemy capture of classified materials a major reason for scuttling ships in WWII?

Classified items like code machines and books held critical secrets. Destroying these ensured the enemy couldn’t decrypt messages or gain strategic advantages. Sometimes these materials were discarded separately, but scuttling was a sure way to protect key intelligence.

How did scuttling help deny technical intelligence to the enemy?

Captured ships revealed details about enemy technology. Knowing an opponent’s radar or torpedo specs gave an edge. Scuttling stopped the enemy from studying a disabled ship’s design, armaments, and tech, preventing improvements in their own defensive systems.

What role did pride and honor play in the decision to scuttle ships?

Commanders often chose scuttling to avoid the enemy physically capturing their vessel. It was about preventing the shame and propaganda value that came with losing a ship intact. This also helped keep the enemy unaware if the ship was compromised or salvaged.

Why were damaged ships sometimes scuttled to improve navigational safety?

In blackout conditions, crippled ships in busy lanes posed collision risks. Scuttling removed these hazards, protecting other vessels. This was crucial in wartime when many ships traveled without lights to avoid enemy detection.

How did logistical and practical issues influence scuttling decisions?

Recovering damaged ships required safe, feasible, and cost-effective operations. Often, enemy control or long distances made salvage impossible. Scuttling prevented wasting resources on impossible recoveries when towing or repairs weren’t practical.