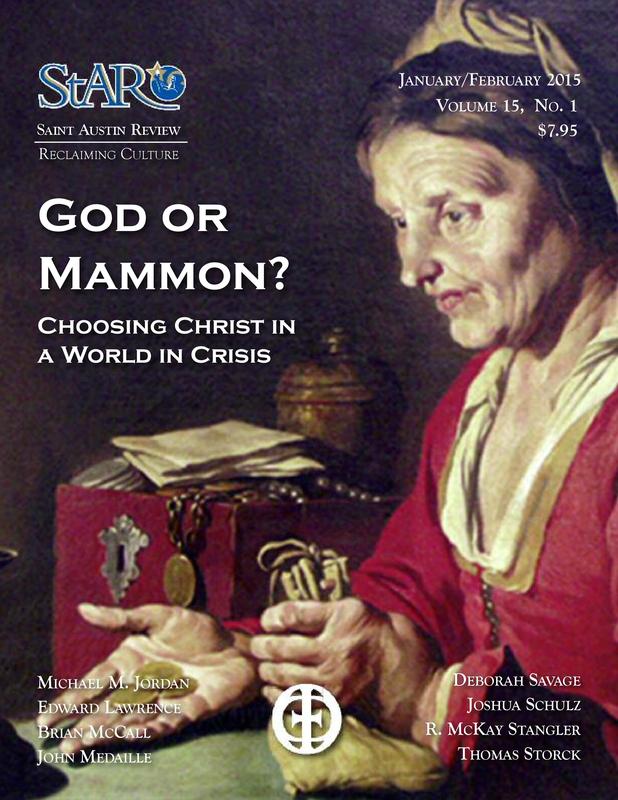

Mammon, mentioned in the Bible, is not an actual god worshiped by anyone but rather an illustrative device symbolizing material wealth or greed. The term appears only four times in the New Testament, specifically in the Gospels of Matthew and Luke. These references portray Mammon as the personification of wealth that cannot be served alongside God, emphasizing the moral conflict between spiritual devotion and materialism.

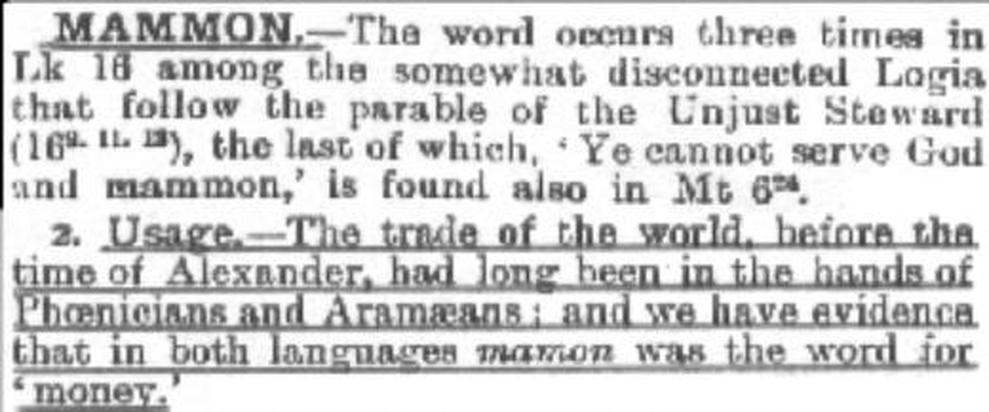

The word “Mammon” derives from the Greek μαμωνᾶς (mamōnas), which transliterates the Aramaic מָמוֹנָא (māmōnā), meaning material wealth or possessions. This term is unusual in the Greek New Testament because it preserves its Aramaic origin, likely reflecting the language spoken by Jesus and his early followers. The New Testament presents Mammon either as a proper noun in parallel opposition to God or as a common noun referring to wealth.

The most significant biblical passages citing Mammon include Matthew 6:24, which states one cannot “serve God and mammon,” and Luke 16:9-13, where Mammon appears multiple times in a parable about faithful stewardship. The use of Mammon in these contexts emphasizes the choice between serving God or serving money, constructed as mutually exclusive masterships.

The Bible itself does not present Mammon as a deity or a figure being worshiped. Instead, Mammon is a literary personification of wealth or greed. This rhetorical device aligns with other biblical personifications such as Paul’s analogy in Philippians 3:19, where the “stomach” is called a god, highlighting indulgence and desire in human behavior. Likewise, the Greek god Ploutos personifies wealth symbolically; Mammon functions within this tradition but without actual cultic worship.

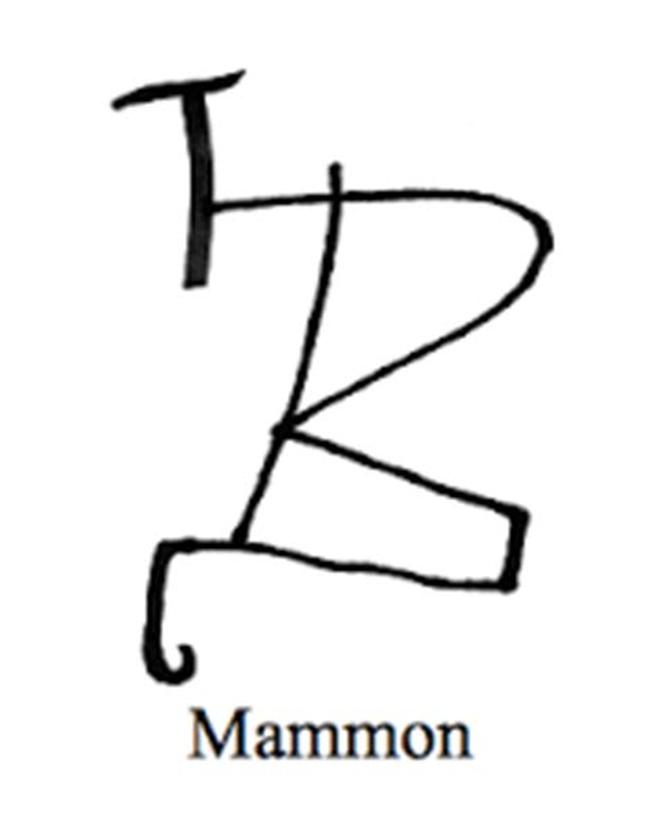

Historical and academic scholarship rejects the idea that Mammon was an actual god or object of worship. Notably, scholars such as Dale Allison and W.D. Davies dismiss claims from some 19th-century sources that Mammon was a Syrian deity. The authoritative Dictionary of Deities and Demons in the Bible (DDD) similarly finds no evidence supporting Mammon as a cultic figure. Rather, the notion of Mammon as a demon or evil god in medieval Christian writings stems from an interpretative development where early translators and theologians personified wealth as an enemy to spiritual fidelity.

In church history, Jerome’s Latin Vulgate translation preserved Mammon as mammona without translating it, which encouraged medieval thinkers to treat Mammon as a proper name and demonize it. As a result, later Christian tradition personified Mammon as an evil spirit of greed. Modern Bible translations tend to avoid this personification. Versions like the New Revised Standard Version (NRSV) usually translate the word as “wealth” or “money,” eliminating any implication that Mammon is a godlike entity.

Mammon’s cultural and linguistic background is important. The Aramaic term was common in Jewish and early Christian communities, sometimes neutral, referring simply to property or money. For example, rabbinic literature, including the Talmud, uses the root word without demonizing it. The biblical New Testament’s use of Mammon serves a theological and moral purpose rather than describing an actual deity or cultic practice.

Early Jewish thought and Second Temple Judaism contain multiple warnings about the dangers of wealth. Texts like Sirach 31:7 caution against overvaluing Mammon, reflecting a broader ethical concern within the cultures that influenced Christian scripture. This context supports understanding Mammon less as a god and more as an emblem of material temptation that rivals devotion to God.

| Aspect | Fact |

|---|---|

| Biblical mentions | Exactly four times (Matthew and Luke Gospels) |

| Meaning of Mammon | Material wealth or possessions (Aramaic origin) |

| Worship evidence | No historical evidence or practice of worship |

| Personification | Later Christian tradition personified as demon/god of greed |

| Modern translations | Translate as “wealth” or “money” instead of a deity |

The following key points summarize Mammon’s role and interpretation:

- Mammon is a New Testament term for wealth, not an actual deity worshiped in history.

- It appears only four times in the Gospels, emphasizing moral choices about materialism.

- Originally a neutral term in Aramaic used for money or property.

- Later Christian thinkers personified Mammon as a demon linked to greed.

- Modern scholarship and translations confirm it is an illustrative device, not a worshiped god.

Was Mammon Really Worshiped or Just a Biblical Figure of Speech?

Short answer: Mammon was never genuinely worshiped as a god by any group; it’s rather a biblical literary device used to represent wealth, especially material greed. The Bible’s few mentions of Mammon personify money as something competing with God for loyalty, but no historical evidence supports Mammon as an actual deity or object of worship.

Sounds straightforward, right? But the story isn’t just black and white. Let’s unpack the curious case of Mammon, the ‘god’ of gold, and see how this idea evolved from Aramaic slang to medieval demon tales, and finally to modern Bible translations.

What Does the Bible Actually Say About Mammon?

First, trivia alert: despite some myths, the Bible contains exactly four references to Mammon. All are found in two New Testament gospels—Matthew and Luke—and none elsewhere. It’s more cameo than main character. So, the biblical Mammon isn’t a “many times mentioned” figure, but a selected symbol.

- In Matthew 6:24, Jesus warns you cannot “serve God and Mammon.”

- In Luke 16:9-13, Mammon appears three times quickly within a parable, emphasizing the choice between God and wealth.

The word Mammon (Greek: μαμωνᾶς, transliterated from Aramaic māmōnā) simply meant material wealth or possessions. It’s like saying “the almighty dollar,” but in Aramaic. This is not a unique name but a common noun for property or riches.

Personification: When Wealth Gets a Face

What grabs attention is the way Mammon is portrayed—as something that one can “serve.” This flips wealth from a cold, inert thing into an active, rival “master.” An early biblical rhetorical device, this personification was a way to make a moral lesson vivid. You aren’t just greedy; you’re worshiping money as if it were a god.

Paul had a similar twist calling the stomach a “god” (Philippians 3:19) to critique gluttony. So treating abstract concepts like wealth as “masters” fits a larger biblical style of moral teaching.

Did Anyone Actually Worship Mammon?

Here’s where the confusion kicks in. Rare nineteenth-century scholars speculated Mammon was a real Syrian deity. But this conjecture is now firmly rejected by modern scholarship. Authorities like Dale Allison and W.D. Davies explicitly dismiss Mammon as a worshiped god.

Leading reference works such as the Dictionary of Deities and Demons in the Bible say the personification of Mammon as a demon or god is a later Christian invention, emerging around the medieval period.

In truth, no archaeological or textual evidence shows any tribe or culture actually worshiped Mammon as a deity. The idea of Mammon as an evil spirit ruling wealth took shape much later, partly due to translations like Jerome’s Latin Vulgate leaving the term untranslated as “mammona.” This fed medieval imaginations, turning abstract criticism of greed into a battle against a demon named Mammon.

The Language Angle: Why Was the Aramaic Term Preserved?

The original Gospels were written in Greek but sometimes kept Aramaic words like “Mammon” untranslated. Scholars see two reasons:

- To preserve the authenticity and original flavor of Jesus’ sayings, since he likely spoke Aramaic.

- Or as a literary device, adding exotic weight to the message for Greek-speaking audiences.

So the unusual retention of the word Mammon likely aimed not to name a god, but to emphasize the tangible reality of wealth that competes with God for allegiance.

How Interpretations of Mammon Changed Over Time

Interestingly, translations influence how readers perceive Mammon:

- King James Version (KJV) keeps it as “Mammon,” helping provoke the idea of a distinct entity.

- Modern translations, like the New Revised Standard Version (NRSV), simply say “wealth” or “money,” dropping the personification.

Medieval Christianity took a giant leap. Following Jerome’s lead, clerics turned Mammon into a demon—a proper evil god of greed. This demonization underscored the moral battle: not just avoiding greed, but fighting a spiritual enemy.

Context Matters: Second Temple Judaism and Early Christianity

Jesus’ teachings fit into a broader Jewish tradition concerned with wealth ethics. For example, the Hebrew book Sirach (31:7) warns against wealth’s dangers. In rabbinic texts like the Talmud, “mammon” meant property in neutral terms.

The criticism wasn’t aimed at money itself but at the human tendency to let wealth dominate life and values. The “mammon” imagery in the Gospels simply dramatizes this conflict.

So, What’s the Takeaway?

Mammon in the Bible isn’t a god who ever received worship. Instead, it’s a clever rhetorical figure painting money as a rival master. The term’s personification helps people understand the spiritual and moral danger of greed. Later Christian tradition gave Mammon a spooky persona to warn humanity dramatically. Still, it’s an anthropomorphized concept, not an ancient deity.

For modern readers wrestling with the lure of wealth, the Mammon message remains powerful. It challenges us: who or what do you truly serve? Wealth? God? Or maybe something else entirely?

Practical Tips Inspired by the Mammon Lesson

- Reflect on your priorities: Are you serving material things at the cost of deeper values?

- Practice gratitude: Remind yourself that possessions aren’t masters—they’re tools.

- Stay aware: The Bible’s depiction of Mammon as a rival master calls for vigilance against letting wealth dominate your life’s decisions.

- Read interpretations carefully: Understanding that ‘Mammon’ is not a literal god but a literary image can help prevent confusion and enrich your study.

In short, Mammon is a brilliant biblical shorthand. It’s a flash warning sign flashing: “Beware! Greed can become like a master you serve.” No temples, no rituals, no actual cult—just a vivid depiction of how money can control hearts.

This deep dive clarifies how Mammon’s biblical and cultural journey shapes today’s understanding: a timeless caution masked in a name that sounds like a deity but serves as a mirror to human desire.