Historians often mark 1453 as the end of the medieval period rather than 1461, when the last remnant of the Roman Empire disappeared, because the 1453 fall of Constantinople represents a clearer cultural and historical turning point.

The choice of 1453 is largely symbolic and interpretive. Periodization, or dividing history into eras, is inherently arbitrary. No single date perfectly defines the end of broad periods like the Middle Ages. Instead, historians select events that best illustrate major shifts in political power, society, culture, and technology. While the Eastern Roman Empire (Byzantine Empire) survived in diminishing form until 1461, its decisive collapse occurred with the Ottoman conquest of Constantinople in 1453. This key event is widely accepted as marking the medieval era’s close.

Constantinople was a significant cultural, economic, and military center. Although the empire had weakened for centuries, the city retained symbolic importance as the capital and home of the last Roman Emperor, Constantine XI Palaiologos. Losing Constantinople meant losing the Eastern Roman political entity and the emperor himself. Later successor states, like the Empire of Trebizond, lacked the empire’s former unity or influence. The fall thus marked the definitive end of the Roman imperial legacy in the East.

- 1453 marks a clear rupture: the loss of the last great Byzantine stronghold and emperor.

- The city’s fall ended a millennium-old Christian empire, triggering widespread change.

Additionally, 1453 coincides with other pivotal shifts. The Hundred Years’ War between England and France concluded in the same year, ending a lengthy medieval conflict. The use of cannon artillery to breach Constantinople’s walls symbolized the decline of medieval fortifications and castle warfare. This technological change forced military strategies and political structures to evolve toward centralized states with standing armies, characteristic of the Early Modern period.

The fall of Constantinople also acted as a cultural catalyst. Refugees and scholars fled Ottoman rule, bringing Greek texts and knowledge to Western Europe. This influx helped spark the Renaissance, a flourishing of art, science, and humanism that clearly breaks from medieval traditions.

Many historians endorse the 1453 date for these reasons, though alternate endpoints exist. Some propose 1492 for Columbus’s discovery of America or the end of the Reconquista in Spain. Others suggest the 1517 Protestant Reformation or Gutenberg’s printing press circa 1454 as markers of transition. These differing focuses reflect various cultural, technological, or religious perspectives on when the Middle Ages gave way to modernity.

Notably, linking the Middle Ages’ end strictly to the Roman Empire’s final disappearance is less meaningful. The empire’s fading beyond Constantinople was geographically remote and politically insignificant. Holding onto vestigal remnants does not prevent classifying an era as ended, much as Native American tribes remaining after the American frontier closed does not keep the Old West era alive. The fall of Constantinople represents the last authoritative, significant center of Roman imperial power and culture.

| Aspect | Why 1453 Matters | Why 1461 Is Less Notable |

|---|---|---|

| Political Significance | Loss of Constantinople = loss of capital and emperor | Successor states had no real power or recognition |

| Cultural Impact | Triggered Renaissance by transferring knowledge | Remnants lacked cultural or historical influence |

| Military Changes | Cannon siege marks end of medieval fortifications | No new significant military events associated |

| Historiographic Use | Widely accepted transition point in Western history | Seen as minor footnote to empire’s lingering presence |

The choice also reflects a Eurocentric view focusing on Western civilization. The fall of Constantinople to a Muslim power marked a critical shift in Christian Europe’s geopolitical environment. Other regions, like Northern Europe or Asia, experienced different timelines and turning points.

In short, 1453 is a convenient and meaningful marker for historians aiming to capture a broad cultural and political shift from medieval to early modern. It is less about the absolute disappearance of the Roman Empire and more about the significance of the event and its consequences.

- The end of the medieval period is an interpretive choice, not a fixed fact.

- 1453 symbolizes the fall of a major cultural and political entity, not just technical empire expiration.

- Technological, military, and cultural changes around 1453 mark a new era.

- The Roman Empire’s lingering until 1461 involved minor, less influential remnants.

- Alternate end dates reflect different perspectives on medieval decline and transition.

Why Do Historians Say the Medieval Period Ended in 1453 When the Roman Empire Didn’t Disappear Completely Until 1461?

Here’s the million-dollar question historians love debating: Why is 1453 marked as the end of the medieval era when the Roman Empire technically limped on until 1461? Let’s cut through the confusion and shed light on this historical conundrum.

First, a quick reality check: period endings like “Middle Ages” are extremely fuzzy. Think of trying to pick the exact moment your favorite TV series ended — one person says after season five, another season seven, and some mourn the final episode forever. It’s a bit like that with history.

Period End Dates: Purely Arbitrary (But Useful)

Historians often pick a year that *feels* like an era’s grand finale. The truth? There’s no magic line in the sand for the Medieval period. According to many scholars, the whole concept of cutting history neatly into periods is arbitrary. There’s an ongoing debate about where the Middle Ages really end. So why 1453?

Because something big happened.

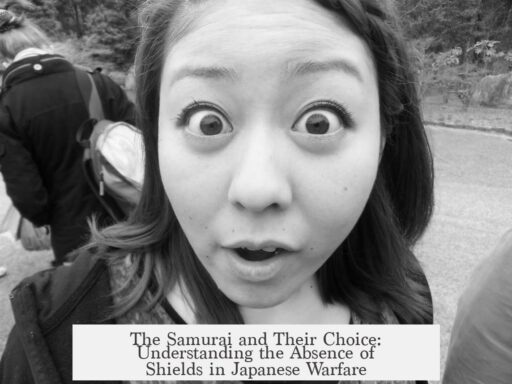

The Big Event: The Fall of Constantinople in 1453

1453 wasn’t chosen because the Byzantine Empire officially vanished in 1461—oh no, the real kicker was the fall of Constantinople itself. This was *the* moment that rocked the medieval world.

Why? Constantinople wasn’t just any city. It was the beating heart of the Eastern Roman Empire—a cultural and economic powerhouse controlling key trade routes, safeguarded by walls so thick and tall they held off invaders for centuries. Its strategic location bridged Europe and Asia, becoming a critical trade hub.

Even in its final days, Constantinople symbolized something mighty. Its fall to the Ottomans sent shockwaves through Europe. The loss wasn’t just military—it was symbolic. The last true Roman Emperor, Constantine XI Palaiologos, died defending his capital. Without him, the Eastern Roman Empire ceased to exist in any meaningful way.

So really, the empire ended the moment it lost its capital and emperor. The remaining “Roman” states after 1453, including the final date 1461 you mentioned, were mostly insignificant holdouts, lacking real power or recognition.

The Renaissance Trigger: More Than Just a City Falling

Here’s the plot twist: the fall of Constantinople sparked the Renaissance. When the city fell, many Greek scholars, fleeing Ottoman rule, took ancient documents and knowledge with them to Western Europe. This burst of learning rekindled classical philosophy, science, and arts—propelling Europe fast forward out of the medieval mindset.

This migration of intellect transformed Europe, igniting innovations in art and technology. So, 1453 is less about falling walls and more about the dawn of a new age.

Technological Shake-Up: Ownership of Cannons and Castles

Did you know that Constantinople’s walls, famous for centuries, finally fell thanks to cannon fire? Before this, walls and castles were the ultimate defense. The arrival of gunpowder weaponry changed everything.

Cannons crushed the myth of impenetrable fortresses. Suddenly, armies couldn’t just hide behind walls—they needed massive standing forces supported by centralized states with strong bureaucracies. This shift chipped away at feudalism, where knights ruled by sword and castle.

So, 1453 marks a technological turning point: the old medieval order, built on castles and feudal loyalty, started crumbling.

And It’s Not Just Constantinople—1453 Sees Other Big Things

Coincidentally, 1453 also marks the end of the Hundred Years’ War between England and France, another medieval tangle that shaped Europe’s future. With both these major events happening in one year, historians find a neat package: the medieval era folding up, while something new unfolds.

But Wait, There’s More! Alternative Dates for the Medieval End

Look, if you attend enough history lectures (or scroll enough online debates), you’ll find different historians waving different flags for the medieval period’s finale:

- 1455: Gutenberg’s printing press revolutionizes information flow, sparking mass literacy.

- 1485: The Tudor dynasty rises after the Battle of Bosworth, neatly ending England’s medieval conflicts.

- 1492: Columbus discovers the Americas; Granada falls, ending the Reconquista, and Jews get forced out of Spain. Talk about drama!

- 1500 or 1517: The start of the Protestant Reformation with Martin Luther’s 95 Theses—religious upheaval reshaping Europe.

So, if you’re thinking, “Hey, shouldn’t the end of the medieval era be flexible?” you’re right! Different aspects of medieval life—culture, technology, politics—evolve at different times. Maybe it’s more like waves than a single cliff.

Why Not Use 1461, Then?

Some might wonder why not just stick with the Roman Empire’s very final disappearance in 1461 to mark the end. The answer: the remnants of the Roman Empire after 1453 were tiny, politically irrelevant, and disconnected.

It’s like a famous celebrity losing their spotlight but still being around for a week or two, living off past glory—technically they’re not “gone,” but their cultural impact is zero. Trabizond, the last Roman realm until 1461, was more a relic than a power player.

So, historians see 1453 as the more meaningful, impactful date when the Roman legacy faded into history’s horizon.

What About Regional Differences and Other ‘Medieval’ Timelines?

Here’s another twist: history isn’t the same everywhere. The “medieval period” in Europe might end in 1453, but in Finland, the Iron Age ended around the 13th or 14th century. Japan’s medieval ages don’t overlap with Europe’s at all.

This means any general statement about period endings is a broad brush—always consider where you’re looking. For Western Europe, balancing the fall of Constantinople with the Hundred Years’ War’s conclusion makes solid sense.

The Plague and Social Upheaval: Another Hidden Ending?

Some scholars argue the Middle Ages ended way earlier—around the 13th century thanks to the plagues sweeping Europe. The Black Death shook people’s faith in institutions, including the Church, changing society’s political and economic landscape.

It’s fair to say the medieval world was unraveling for a while before 1453. But this unraveling was slow and gradual, not a big-bang moment.

Putting It All Together: The Medieval End is a Cocktail of Events

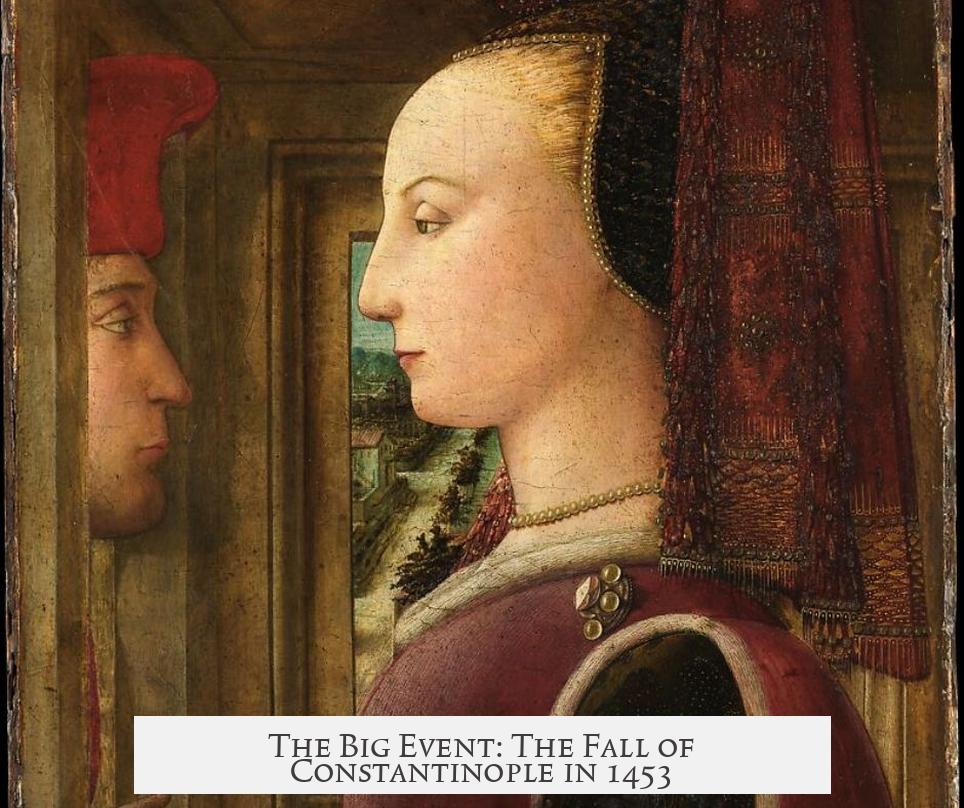

| Factor | Why It Matters |

|---|---|

| Fall of Constantinople (1453) | Loss of Eastern Roman Empire, triggered Renaissance, symbolized medieval decline. |

| End of Hundred Years War (1453) | Ended feudal conflicts; shifted toward centralized nation-states. |

| Gutenberg’s Printing Press (1454–55) | Mass literacy exploded; ideas spread faster than ever. |

| Technological Advances | Cannons ended castle defenses and feudal dominance. |

| Social Changes | Plague and changing political power eroded medieval norms. |

Essentially, 1453 stands as a symbolic and practical nexus. The Roman Empire’s death was staggered and messy, but losing Constantinople and its emperor shut the curtain in a historical sense.

Why Should You Care?

Understanding this helps unravel history beyond dull dates on a timeline. It teaches us to ask: What really defines an era? Is it the fall of a city, a change in technology, or cultural shifts? It’s all of those—and how they intersect.

Plus, it’s a great party conversation starter. Next time someone says, “The Roman Empire ended in 1461,” you can say, “Sure, but historians picked 1453 because that’s when the medieval world got its wake-up call.”

Final Thoughts and Takeaway

Periods in history are convenient storylines we create to make sense of chaos. 1453 is the best candidate for the medieval period’s end because of its overwhelming symbolic significance—the end of the Eastern Roman Empire’s heart, a catalyst for Renaissance, a technological shake-up, and a political turning point.

The Roman Empire’s “complete disappearance” wasn’t a single event but a slow fade. The little-known successor state in 1461 wasn’t the empire’s grand finale—just an epilogue.

So, if you want to impress your friends or just sound like a history pro, remember: the Middle Ages didn’t just end; they *evolved* out of existence.

And isn’t that just like history—messy, complicated, and endlessly fascinating?