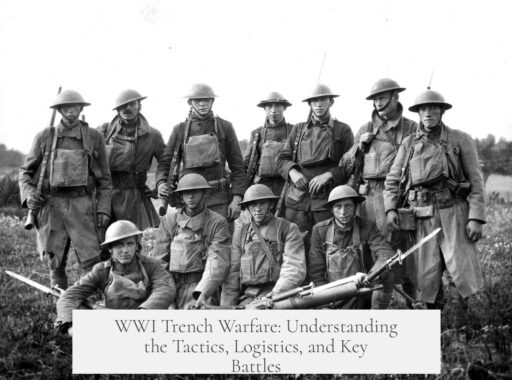

WWI trench warfare was a complex system of fortified positions, carefully built and maintained to hold territory and launch attacks. It involved networks of trenches, defensive works, and evolving tactics designed to break stalemates and manage the deadly conditions of No Man’s Land.

The origin of trench warfare on the Western Front began in 1914 after the German retreat from the Marne offensive. Germans dug in along high ground in France and Belgium, creating strong defensive lines on chalk ridges, which often spared them from the muddy conditions seen by British and French troops. This initial entrenchment was driven by German panic; their quick offensive had stalled. They aimed to buy time, expecting an easier breakthrough that never materialized.

The period known as the Race to the Sea followed, with both sides continuously digging and extending trench lines to outflank one another, pushing their networks toward the Atlantic. These trenches ran parallel, often between 100 and several thousand yards apart, connected with secondary and tertiary lines, and linked by communication trenches. Trenches were zig-zagged to limit the range of shell splinters and included firing steps, sandbag walls, dugouts for shelter, and concrete pillboxes later in the war. Defensive networks also incorporated natural and man-made structures such as town ruins and woods.

Contrary to popular belief, attackers did not simply charge in mass waves across No Man’s Land. The image of “lions led by donkeys” — brave soldiers senselessly thrown at machine guns — is largely a post-war myth from the 1960s associated with antiwar sentiment. British tactical doctrine evolved to give lower-level officers discretion to use stealth and careful approaches. Troops would creep forward, establish forward positions, or build shelters in no man’s land for surprise attacks. Command leadership, however, often clung to outdated Napoleonic concepts, hoping to create breakthroughs for cavalry charges, which rarely succeeded.

Attacks typically started with intense artillery bombardments to destroy enemy trenches, dugouts, and barbed wire defenses. Mines and gas were also used to disrupt defenders, though gas was weather-dependent. A creeping barrage, a moving wall of artillery fire, helped infantry advance behind protection. By 1917, “Bite and Hold” tactics became standard, focusing on capturing specific trench lines and consolidating before pushing forward again.

The German army adapted, often abandoning established trenches under attack to engage in more mobile defense of zones rather than fixed lines. This tactic, partly in response to tanks and changing Allied methods, aimed to maintain flexible control of contested areas.

Captured trenches immediately faced counterattacks supported by artillery and machine guns. Combat shifted toward combined arms tactics, where small infantry units (8-16 men) coordinated closely with tanks, aircraft, and artillery. This ensured attacks were better planned and supported.

| Aspect | Details |

|---|---|

| Trench Structure | Zig-zag layout, firing steps, dugouts, communication trenches. |

| Tactics | Creeping barrages, Bite and Hold, zone control, combined arms. |

| Equipment | Lewis guns, barbed wire, mines, poison gas, tanks (post-1916). |

| Command | Empowered lower commanders, evolving from rigid to flexible attacks. |

The war’s logistics played a key role. Advances in supply chains, finance, and new weaponry like Lewis guns and rail guns gave the Allies an edge. On the Eastern Front, trenches were used but geography and loose Russian command allowed more movement and unpredictability.

While German forces focused on fortifying captured ground, the British viewed trenches temporarily, aiming to break the stalemate. Battles were often tactical rather than strategic, with front lines shifting frequently due to artillery barrages and small assaults.

Overall, trench warfare evolved drastically over the war. Early large-scale attacks differed from later combined arms operations. The arrival of American forces and new technology in 1918 helped break the deadlock, signaling the end of static trench warfare and a return to mobile warfare.

- WWI trench warfare involved complex networks and fortifications, not just simple lines.

- Attacks combined artillery bombardment, creeping barrages, and well-planned infantry advances.

- The myth of mass wave assaults is largely inaccurate; lower-level commanders used flexible tactics.

- Combined arms coordination and logistics advances shaped late-war strategies.

- Trench warfare evolved over time and differed between Western and Eastern Fronts.

How Did WWI Trench Warfare Actually Work?

Trench warfare in World War I was a complex, brutal, and evolving system of static defense and slow, grinding attacks. It wasn’t just lines in the mud; it was a labyrinthine network of fortifications, tactics, and strategy that shaped the entire Western Front. So, how did all this actually work?

Let’s dig in — pun intended — and unravel the reality behind those muddy ditches, barbed wire, and omnipresent danger.

Getting Into the Trenches: Where It All Began

In 1914, the Germans initially surged westward during their Schlieffen Plan offensive, expecting a quick knockout of France. But after the Battle of the Marne, that rapid advance stalled dramatically. Instead of retreating further, the Germans dug in, creating trenches on high ground across France and Belgium.

This high position meant German troops often avoided the stereotypical mud so emblematic in British and French imagery. Their trenches sat along chalk ridges, giving them better drainage and less sludge to deal with.

Interestingly, older views saw the trenches as slow, deliberate fortifications meant to buy time and build forces. Yet, newer research, including Soviet archives discovered decades later, reveals the Germans were panicked. Their swift advance was halted earlier than expected. The trenches became desperate holding patterns while waiting for reinforcements — not a planned static defense from the start.

Meanwhile, the Allies tried to outflank the Germans at every turn, causing a so-called Race to the Sea. Both sides endlessly extended trenches northward, trying to avoid being flanked, until the front lines ran all the way to the Atlantic coast. This long “no man’s land” was the defining geography of the Western Front for years.

Building the Trenches: More Than Just a Hole in the Ground

This wasn’t just digging a trench and calling it a day. Engineers and soldiers developed highly sophisticated trench systems. They zig-zagged trenches to contain shell explosions, cutting down the risk of lethal shrapnel flying along a straight line and hitting dozens of men.

Trenches had several layers:

- Frontline trenches: Where soldiers fought and defended.

- Reserve trenches: Further back, housing reinforcements.

- Communication trenches: Connecting all parts and allowing movement without exposure.

Beyond that, trenches had firing steps for soldiers to shoot from, sandbags for protection, and dugouts — underground shelters to survive enemy artillery barrages. Some places even saw concrete pillboxes for extra defense.

The network wasn’t isolated. Trenches incorporated cellars, ruins, woods, and roads to strengthen their positions, blending natural and man-made defenses.

Wave Attacks? More Like Careful Steps Forward

Forget the myth of soldiers blindly charging in massive waves. That popular picture — men lined up, marching straight into machine-gun fire — is mostly a post-WWII invention, fueled by antiwar sentiments during the Vietnam era.

The reality was smarter and messier. British commanders often empowered officers down to the platoon level to execute varied tactics. Men would creep forward under cover at night, dig advance trenches, or even build shelters in no man’s land. These tactics helped protect men before an attack.

Still, the British high command initially stuck to an outdated Napoleonic mindset. They imagined breakthroughs wide enough for cavalry charges to pour through. It didn’t work. The static nature of trench warfare clashed with traditional battlefield ideas.

The Rhythm of Attacks: Artillery, Barbed Wire, and Infantry Advances

Attacks had a typical pattern. First came brutal artillery bombardments aiming to destroy enemy trenches and dugouts. High explosives shattered the landscape, while specialized shrapnel shells cut through barbed wire defenses — an essential step to allow infantry to advance.

Mines occasionally blew up pockets in the enemy lines. Poison gas was sometimes used but had to be delivered carefully depending on wind, making it risky.

The infantry assault was far from a blind charge. Later in the war, both sides used a “creeping barrage,” a moving curtain of artillery fire just ahead of the infantry’s advance. Soldiers would sprint forward just behind this shield, keeping the enemy suppressed.

By 1917, “Bite and Hold” tactics became common: troops took a small section of enemy lines, fortified it immediately, and then prepared for further attacks.

The Germans had to adapt as well. Tanks and new Allied tactics forced German troops to abandon rigid trench lines. They shifted to more flexible zone defense, scattering rather than clustering in trenches to avoid being easy targets.

Counter-attacks followed every gain. Once an enemy trench was captured, artillery and machine guns covered infantry attempting to recapture lost ground. The battlefields were in a constant state of flux, though with slow and bloody progress.

Combined Arms and Modern Warfare Beginnings

By the war’s later stages, combat was evolving into combined arms warfare, teaming small groups of specialized soldiers with tanks, aircraft, and coordinated artillery. Eight to sixteen men might form small assault teams tasked with targeted objectives rather than bulk frontal assaults.

Communication and coordination improved markedly. Artillery fire finally paired tightly with infantry movements, making attacks more effective and lethal.

Logistics: The Unsung Backbone

While it’s easy to focus on battles, many key innovations weren’t glamorous but vital. The introduction of Lewis Guns — early portable machine guns — rail guns, and advances in supply chains and finance enabled the Allies to sustain prolonged campaigns.

Logistical superiority often dictated the ability to keep firing and attacking, which made war efforts on the Western Front a grueling war of attrition.

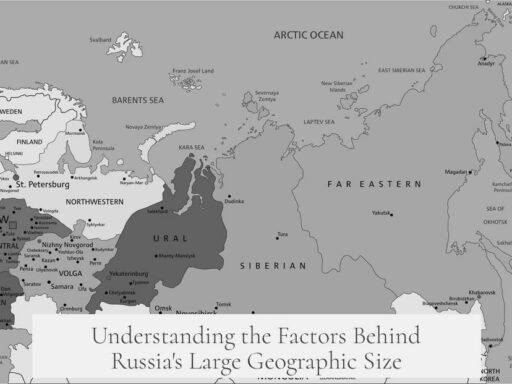

Evolving Fronts and Different Battles

The Eastern Front, where geography and command were very different, didn’t see the same trench stalemate. Movement was more fluid compared to the glued-down Western Front. That front had more random outcomes due to the less rigid Russian army command structure and the terrain itself.

Back west, trenches solidified quickly in 1914. Germany pushed as hard as possible but then had to dig in and fortify what was conquered. The British viewed their trenches as temporary, a stopgap until they could break through enemy lines. This constant mental and physical tug-of-war defined trench warfare.

Interestingly, most battles were tactical rather than grand strategic movements. Lines shifted, often just yards, through raids, shelling, and localized attacks.

Over time, attack strategies evolved substantially. Early-war assaults looked completely different from late-war combined arms offensives after American troops brought fresh energy to the front.

So, What Can We Take Away From This?

WWI trench warfare was no simple story of grim men stuck in mud. It was an intricate, deadly chess match involving careful engineering, evolving tactics, and immense human endurance. The trenches were part prison, part fortress, and part battlefield stage for one of history’s longest and bloodiest stand-offs.

Understanding trench warfare helps us appreciate how modern warfare began to shift from massed armies clashing in fields to complex, technology-driven combined operations.

Next time you picture WWI trenches, think of them as a vast, living network — a brutal ecosystem where soldiers, engineers, generals, and technology battled stubbornly for inches of land under a sky filled with artillery smoke.

How might today’s warfare look if it had to unfold in trenches? Would drones and precision strikes replace creeping barrages? That’s a different story—but it all started in those muddy trenches over a century ago.

How were trenches designed to protect soldiers from enemy fire?

Trenches were built in a zig-zag pattern. This kept shrapnel from traveling the length of the trench when shells exploded. They included firing steps, sandbag walls, shelter dugouts, and concrete pillboxes for added protection during bombardments.

Did soldiers charge enemy trenches en masse like in movies?

Mass wave attacks are mostly a myth. Commanders often let small units move forward carefully using shell holes and forward shelters. Commanders adjusted tactics to reduce losses and close in on enemy lines step by step.

What was the role of artillery before and during an infantry attack?

Artillery first targeted enemy trenches and barbed wire to break defenses. A creeping barrage of shellfire moved ahead just before infantry advanced, shielding them and suppressing enemy fire on the battlefield.

How did trench warfare tactics change by 1917-1918?

By then, “Bite and Hold” tactics became common, where attackers captured a section of trench and held it while preparing for another push forward. German troops began scattering under attack instead of holding static lines.

Why did the Western Front trench lines become fixed early in the war?

Germany’s rapid advance in 1914 slowed, leading them to dig in and fortify captured ground. Both sides dug extensive parallel trenches connected by communication paths, turning battle into a slow, fortified stalemate.