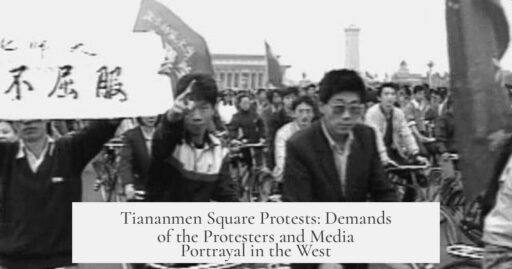

The Tiananmen Square protesters primarily demanded greater political freedom, government transparency, anti-corruption measures, freedom of the press, and increased social protections amid economic difficulties. Western media often oversimplifies these demands, portraying the movement as solely anti-government unrest and ignoring internal CCP factionalism and reformist sympathies within the Chinese leadership.

The protests began soon after the death of Hu Yaobang on April 15, 1989. Hu was a reformist leader who supported political openness, economic liberalization, and reducing corruption within the Communist Party. His death became a catalyst for students and intellectuals seeking to revive and expand reform efforts. The protesters initially identified as patriotic communists wishing to reform, not overthrow, the Party.

Seven core demands were articulated by April 17, 1989:

- Recognition of Hu Yaobang’s views on democracy and freedom as correct.

- Admittance that previous campaigns against spiritual pollution and bourgeois liberalization were wrong.

- Full disclosure of the income of state officials and their families to combat corruption.

- Permission for privately run newspapers and an end to press censorship.

- More funding for education and better pay for intellectuals.

- Removal of restrictions on demonstrations in Beijing.

- Objective and fair media coverage of students and their demands.

These demands reflected broader societal issues emerging in the late 1980s. Economic reforms had increased inflation and corruption, leading to dissatisfaction among workers and students. Workers lacked independent unions and faced wage erosion, while many students worried about job prospects amidst rising competition and nepotism. Protesters sought solutions that balanced economic liberalization with social protections and political openness.

Inside the Chinese Communist Party, leadership was divided. Reformist “market liberals” led by Zhao Ziyang, supported dialogue and sympathized with many student goals. The conservative faction, led by Premier Li Peng, opposed the protests and advocated for a hard crackdown. Western media often misses this nuanced internal conflict, instead portraying China as a monolithic military state.

Western media coverage commonly uses terms such as “Tiananmen Square Massacre” or “Tiananmen Square Crackdown.” These portrayals emphasize the violent suppression by the military on June 3–4, 1989, in which hundreds or possibly thousands of demonstrators and bystanders were killed. However, much of the actual violence occurred along Chang’an Avenue and other areas adjacent to but outside Tiananmen Square. Furthermore, protests spread to many cities beyond Beijing, which Western narratives sometimes overlook.

Western accounts frequently frame the protests as revolutionary uprisings rejecting economic reforms, yet this mischaracterizes the complexity of the movement. Protesters did not oppose economic liberalization; many supported it alongside demands for political reform. The movement aimed for transparency, rule of law, and political liberties, not a wholesale rejection of market reforms.

The crackdown and repression delayed China’s reform path by about a decade. The conservative faction within the CCP regained control, purging reformists and limiting political openness. Some reformers, including Zhu Rongji, later resumed limited economic and administrative reforms, illustrating ongoing factional tensions within the Party.

Methods of protest were largely nonviolent, including hunger strikes, sit-ins, and civil disobedience. Though a few incidents involved rioting, the movement’s core was peaceful advocacy for reform. The Chinese government responded with mass arrests, censorship, and a violent military crackdown, which Western media extensively reported, resulting in arms embargoes and sanctions by Western countries.

| Aspect | Details |

|---|---|

| Main Protester Demands | Political freedom, anti-corruption, transparency, press freedom, education funding, demonstration rights |

| Protest Nature | Reformist, patriotic communists; not revolutionary or anti-economic reform |

| Chinese Leadership | Divided between market liberals (Zhao Ziyang) and neo-conservatives (Li Peng) |

| Western Media Portrayal | Emphasizes violent crackdown; tends to oversimplify China’s political dynamics; sometimes mislabels the protests |

| Impact of the Crackdown | Suppression of protests, purging reformists, delayed liberal reforms, strengthened conservative control |

In essence, the Tiananmen protests were a complex movement demanding political and social reform within the existing system. Western media often presents them as a tragic, simplistic struggle between authoritarianism and democracy, overshadowing internal Chinese debates and the protesters’ reformist intentions.

- Protesters sought transparency, anti-corruption, press freedom, and political liberalization while supporting economic reforms.

- The movement was rooted in dissatisfaction with inflation, corruption, and social inequalities exacerbated by rapid economic change.

- Chinese Communist Party leadership was factionalized; some supported dialogue, others pushed for suppression.

- Western media highlights the violent crackdown but often misses the protests’ nationwide scope and nuanced goals.

- The crackdown delayed reforms, empowered conservative forces, and complicated China’s development trajectory.