The last known auroch died in 1627 despite 400 years of royal hunting restrictions because these proto-conservation laws addressed only hunting and did not solve critical ecological and genetic problems.

The aurochs originally thrived in open plains and mixed landscapes. By the last centuries of its existence, it was confined to old growth forests, which were not its preferred habitat. This habitat loss forced the aurochs into marginal areas where food and breeding conditions were suboptimal, limiting population growth.

Genetic isolation became a major issue. The remaining aurochs populations grew increasingly inbred. Prolonged inbreeding typically reduces fertility and increases health problems, as observed in other species facing bottlenecks, such as the black-footed ferret. Although detailed genetic data are lacking, similar patterns likely occurred in aurochs, lowering reproduction rates.

Population dynamics naturally depend on birth rates keeping up with deaths. Even with hunting restricted, the auroch’s reproduction rate diminished due to genetic decline. This imbalance caused a gradual population decrease that legal protections alone could not halt.

While royal laws from the 1200s protected aurochs from hunting, these regulations did not address broader issues. They failed to prevent habitat degradation or mitigate genetic bottlenecks. Proto-conservation focused narrowly on controlling human hunting but overlooked ecological management or genetic rescue.

| Factor | Effect on Aurochs Survival |

|---|---|

| Habitat Loss | Forced into unsuitable old growth forests |

| Genetic Isolation | Inbreeding reduced fertility and health |

| Population Dynamics | Low reproduction could not offset mortality |

| Royal Hunting Restrictions | Controlled hunting, but no broader conservation |

The aurochs’ extinction highlights that banning hunting alone cannot preserve species. Effective conservation requires habitat protection, genetic diversity maintenance, and population support. The aurochs case shows how exclusive focus on a single threat—hunting—fails when other factors threaten survival.

- Habitat compression forced aurochs into marginal environments.

- Genetic bottlenecks caused reproductive failures.

- Population decline continued despite hunting bans.

- Proto-conservation lacked integrated ecological strategies.

How Did 400 Years of Proto-Conservation Fail to Save the Auroch?

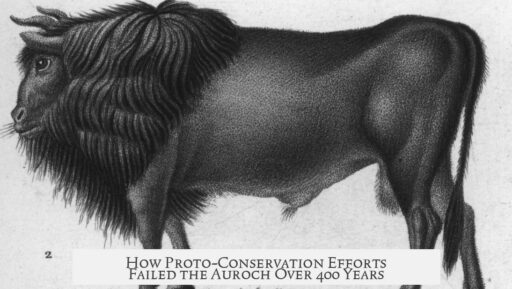

The last known auroch died in 1627 despite royal hunting restrictions dating back to the 1200s. How could centuries of “proto-conservation” fail to prevent extinction of such a majestic, high-status creature? At first glance, it seems baffling. After all, if kings were guarding the aurochs with legal decrees, how did it slip through the cracks? Let’s explore the tangled web of habitat, genetics, and biology that made royal laws helpless guardians.

The Aurochs’ Decline—More Than Just Hunting

To understand the failure, we must start by acknowledging that hunting bans alone weren’t enough. Kings might have claimed, “No hunting the aurochs!” but the creatures found themselves trapped in shrinking pockets of forest that weren’t their true home. The aurochs thrived on open plains and mixed landscapes—not dense old growth forests where the last populations eked out survival.

Forced retreat into marginal habitats cut deeply into their chances. Classic case of “home sweet home” ripped away. Imagine being a plains-loving buffalo shunted into a thick, gloomy forest where food is scarce and navigation tricky. Survival becomes an uphill battle.

Habitat—Not the Right Address for a Thriving Species

The last aurochs in Poland were *king of the forest* by default, not preference. By the 1600s, open mosaics of plains and scrub had given way to agricultural fields and human settlements. The remaining patches were dense forests—their final refuge. Unfortunately, these weren’t ideal ecosystems for a giant herbivore that preferred varied landscapes.

This habitat compression meant less food and fewer breeding territories. Restricted space also piled aurochs together, creating crowding that invited disease or stress.

Genetic Isolation—The Silent Killer

More insidious than habitat loss was genetic decay. Over centuries, aurochs became isolated in small populations, limited to those last forested refuges. This forced inbreeding—a genetic bottleneck that devastates species.

“We don’t have detailed genetic data from those ancient aurochs, but biology teaches us a harsh lesson: long-term inbreeding shrinks vitality and fertility.”

Compare to the black-footed ferret today, a species that suffered a similar bottleneck. Males showed low sperm motility and even missing testicles, making natural reproduction tough. Something similar likely happened with the aurochs. Low fertility means fewer calves, and fewer calves mean population shrinkage no hunting ban can stop.

Population Dynamics—Numbers Don’t Lie

Decline in numbers follows simple math: birth rate minus death rate. If auroch calves born each year don’t replace adults dying of age or disease, the population inevitably sinks. Their reduced fertility and squeezed habitats caused births to lag behind losses.

Even under royal protections, auroch numbers dwindled. Hunting restrictions preserved individuals from hunters’ arrows but couldn’t boost reproduction or restore lost habitat.

Proto-Conservation—Noble Intent, Limited Impact

It’s remarkable that medieval rulers cared enough to restrict auroch hunting around 1200, signaling an early awareness of conservation needs. But this “proto-conservation” is narrow in scope—focused solely on human killing of animals. It doesn’t consider habitat protection, genetic health, or ecological balance.

Royal laws were like installing a seatbelt but ignoring the faulty brakes and bald tires on a car headed for a cliff. The aurochs’ extinction was driven by complex forces beyond mere hunting.

Lessons from Auroch’s Fate

| Cause of Failure | Explanation | Modern Conservation Parallel |

|---|---|---|

| Habitat Loss and Degradation | Aurochs confined to old growth forests, unfavorable for survival. | Similar to many species today confined to fragmented habitats. |

| Genetic Isolation and Inbreeding | Bottleneck lowered fertility and health. | Seen in endangered species like Florida panther genetically rescued by gene flow. |

| Population Dynamics | Reproduction rates couldn’t keep up with natural mortality. | Modern population viability analyses monitor such trends. |

| Limited Focus of Conservation | Only hunting restricted; no habitat or genetic management. | Today’s holistic conservation addresses multiple factors. |

Why Does This Matter Today?

The aurochs’ tale is more than a medieval curiosity. It’s a cautionary story for modern conservationists. It shows why restricting just one threat—like hunting—is often insufficient. Without considering habitat, genetics, and population biology, species remain vulnerable.

It also highlights the limitations of early conservation efforts. The “proto-conservation” ethic of the Middle Ages was probably well-meaning, maybe even ahead of its time, but it lacked the scientific backing and comprehensive approach needed to save the aurochs.

So next time you hear about ancient royal hunting laws, remember: even kings cannot conserve nature with just rules against hunting. Real conservation demands understanding ecology, genetics, and the subtle balances life depends on.

Aurochs and Ambitions of De-Extinction

Interestingly, the aurochs saga continues today in efforts to recreate or “de-extinct” the species by breeding modern cattle with aurochs traits. These efforts underscore that understanding their past challenges—habitat needs, genetic diversity—is crucial if we ever hope to revive a living reminder of Europe’s wild megafauna.

Could human management and science finally succeed where kings failed? Only time will tell. But the lesson is clear: conservation must be holistic, scientific, and adaptable.

Wrapping it Up

In brief, centuries of royal restrictions failed because:

- They couldn’t stop habitat loss or forced habitat compression to poor areas.

- Genetic isolation led to inbreeding and reproductive failure.

- Population dynamics naturally favored decline despite protection from hunting.

- Legal protections were too narrow, ignoring ecological and genetic realities.

The aurochs’ extinction isn’t a simple story of overhunting. Rather, it’s a complex tale of habitat, genes, and biology slipping through medieval policy cracks. Kings tried to protect a symbol of power; nature demanded a more nuanced approach.

So, next time you hear about a “royal decree” as conservation, smile knowingly. Nature plays by tougher rules, needing more than good intentions and hunting laws.

Why didn’t royal hunting restrictions alone save the aurochs from extinction?

Hunting laws prevented killing but did not stop habitat loss or genetic decline. The aurochs lived in reduced, unsuitable habitats and faced inbreeding, which lowered reproduction. These issues continued despite legal protections.

How did habitat changes affect the aurochs population?

The aurochs were forced into old growth forests, a habitat they did not prefer. This marginal habitat limited food availability and breeding opportunities, reducing their population’s chance to recover.

What role did genetic isolation play in the aurochs’ extinction?

Isolation led to inbreeding and a genetic bottleneck. This caused lower fertility and health problems, similar to what is seen in modern endangered species. It hindered population growth despite conservation laws.

Could proto-conservation efforts have been improved to protect the aurochs?

Yes. Focusing only on hunting restrictions was not enough. Effective conservation would have needed habitat management and genetic diversity preservation to support a healthy, reproducing population.