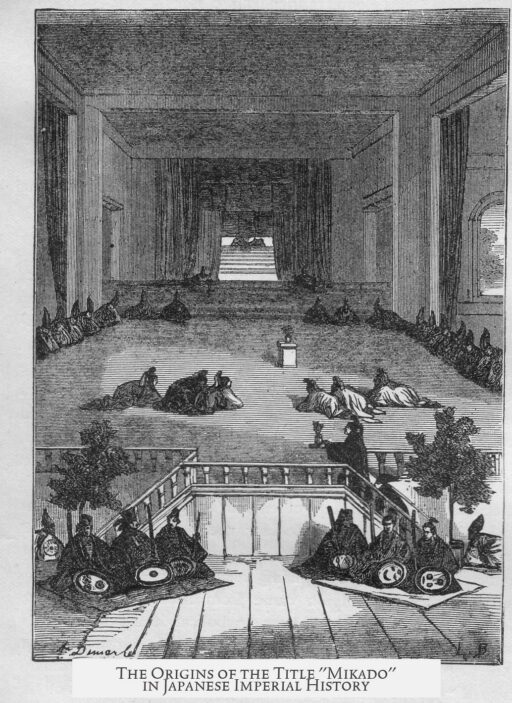

The Emperor of Japan first started to be referred to by the word “Mikado” in an explicit, personal sense around the 11th century, with the term becoming common in literary texts such as the “Hamamatsu Chūnagon Monogatari” by 1062. Prior to this, “Mikado” was mainly used in a toponymical or metaphorical way, often designating the gate to the palace or the imperial court as a whole, rather than a direct personal title for the Emperor.

The term mikado is not an official title but a respectful word used to indirectly denote the Tennō (Emperor). Its etymology includes the honorific prefix mi- and kanji characters that emphasize reverence. Two main kanji representations exist: 帝, linked to the meaning “Son of Heaven,” and 御門, combining mi- with “gate,” symbolizing the palace or the imperial court.

Early occurrences of the kanji 帝 can be traced to the 8th century, such as in the Fūdōki records from 713. However, the reading or usage as the term “mikado” referring to the person of the Emperor at this time remains uncertain. The word appears in the Man’yōshū poetry anthology compiled around 812, but these usages mostly represent the “gate” or act metaphorically to signify the imperial court or government rather than a direct appellation of the Emperor himself.

One notable exception is Man’yōshū poem No. 4480, where “mikado” clearly functions as a direct personal reference to the Emperor:

Fearful, when recalling my revered Lord of Heaven [=Tennō], I cry ceaselessly, day and night.

Despite this early exception, widespread and unambiguous use of “mikado” to mean the Emperor did not emerge until the 11th century. Literary works from this period show a transition in usage. For example, the early 11th century classic Genji Monogatari continues to use “mikado” mostly in the traditional, toponymical sense associated with the palace gate or court. By contrast, the later 11th century tale Hamamatsu Chūnagon Monogatari (circa 1062) frequently uses “mikado” explicitly to denote the Tennō personally, reflecting clear development in the term’s semantic application.

| Period | Usage of “Mikado” | Notes |

|---|---|---|

| Early 8th century (713) | Kanji 帝 appears, no confirmed reading as “mikado” | Uncertain personal reference to Emperor |

| Early 9th century (812) | Present in Man’yōshū poems, mainly toponymical/metaphorical | One poem (No. 4480) likely personal reference |

| Early 11th century | Toponymical usage continues (e.g., Genji Monogatari) | Not yet common as personal reference |

| Mid 11th century (1062) | Frequent explicit usage for Tennō | Hamamatsu Chūnagon Monogatari solidifies personal meaning |

The dual nature of the term complicates tracing its exact personal use. Given that “mikado” can mean “gate,” and that kanji usage was not standardized in early texts, scholars face challenges in isolating unequivocal instances where it refers directly to the Emperor. The term’s toponymical origin means it was often used figuratively for the imperial court or palace location, indirectly signifying the sovereign.

The gradual shift from a metaphorical or place-related reference to a personal appellation corresponds to changes in Japanese literature and court culture during the Heian period. Texts began to use “mikado” more as a respectful synonym for the Emperor in narratives and poetry, a practice reflected in the later literature of the 11th century.

Overall, “mikado” started as a respectful, indirect reference connected to imperial architecture or institution. Early kanji uses dating back to 713 do not clearly confirm personal application, but by the mid-11th century, the word regularly identified the Emperor himself in written works. This evolution shows how language adapts from metaphorical terms to defined personal designations over time.

- “Mikado” is not an official imperial title but a respectful indirect term.

- Its earliest kanji use in 713 does not confirm personal imperial reference.

- 9th century poetry mostly uses it metaphorically, except one notable personal use.

- 11th century literature shows the term increasingly refers explicitly to the Emperor.

- By 1062, in texts like “Hamamatsu Chūnagon Monogatari,” “mikado” is commonly used for the Tennō.

When Did the Emperor of Japan First Start to Use the Title “Mikado”?

The Emperor of Japan first began to be clearly referred to as “Mikado” in a personal sense around the mid-11th century, notably by 1062 in texts like the Hamamatsu chūnagon monogatari. However, the term itself has a long and complicated history that does not involve it being an official title.

Now, let’s unpack why this is both fascinating and a bit confusing. If you’ve been wondering whether “Mikado” was officially stamped on the Emperor’s business card centuries ago, the answer is no. Mikado isn’t a traditional title like “Emperor” or “Tennō” (the Japanese term for Emperor). It’s more like a respectful nickname or poetic way to refer to the monarch without naming him directly.

What is “Mikado”? The Word Behind the Word

The word mikado is a compound. It carries the prefix mi-, which shows respect, somewhat like saying “honorable” before a name. Its kanji (Chinese characters adapted by Japan) are interesting: two common ones are 帝 (teiji, meaning something like “Son of Heaven,” a grand imperial term) and 御門 (mi + “gate”). The “gate” symbolizes the palace or the Emperor’s abode.

This points to an original toponymical meaning. Rather than calling the Emperor by name, people often referenced the place associated with him—for example, the palace gates. Over time, “Mikado” transformed from meaning “gate” to meaning the Imperial Court or government. Think of it as calling a president “The White House” to refer to the person without mentioning them directly.

This usage makes tracing when exactly mikado meant the Emperor personal is tricky. Old texts often use the word mikado ambiguously, sometimes literally meaning “gate” or metaphorically “court.” The kanji choice wasn’t always consistent, adding to the confusion.

The Historical Timeline: Tracing “Mikado”

Let’s stroll through history with some solid milestones to clarify when the term morphs from metaphor to direct imperial reference.

| Period | Usage | Notes |

|---|---|---|

| Early 8th century (713) | Kanji 帝 found in texts like Fūdōki | Unclear if it directly referred to Emperor; no recorded reading as “Mikado” |

| Early 9th century (812) | Multiple uses in Man’yōshū poems, mostly toponymical/metaphorical | One outstanding poem (#4480) uses mikado personally |

| Early 11th century | Continues to be mostly toponymical/metaphorical (e.g., Genji monogatari) | Does not usually mean Emperor directly |

| Mid 11th century (1062) | Explicit personal references to Emperor in texts like Hamamatsu chūnagon monogatari | Term used regularly as a synonym for the Emperor |

Early Traces: The 8th and 9th Centuries

Some of the earliest instances of the kanji 帝, which relates to the idea of an emperor as “Son of Heaven,” appear around 713 in Fūdōki documents. But textual evidence leaves us hanging because we don’t know how those kanji were read aloud. Was “Mikado” even said then? Maybe, maybe not.

Later, in the Man’yōshū (circa 812), a collection famous for its rich poetry, the word mikado shows up multiple times. Most usages stick to “gate” or symbolize the government metaphorically. But one poem (No. 4480) offers a twist: it likely points directly to the Emperor himself. It reads—roughly—”Remembering my revered Lord of Heaven, I cry ceaselessly, day and night.” This is one of the rare early personal references hidden in poetic language.

The Transition Through Literature: 11th Century Shift

The eleventh century ups the ante. Publications like the early part of Genji monogatari still lean on the metaphorical angle. For them, “mikado” might be a poetic way to talk about the palace gate or court. But the shift becomes undeniable in the mid-11th century.

Enter the Hamamatsu chūnagon monogatari, dated 1062. This work liberally uses mikado to refer directly to the Emperor himself, treating it as a stand-in for the sovereign’s personal name. Picture it like this: before this era, calling someone “the gate” or “the palace” was a polite indirect way of talking about the Emperor’s office or residence. Afterward, “Mikado” is basically the Emperor’s nickname in stories and common speech—without formal proclamation.

Why Was “Mikado” Never an Official Title?

Here’s the kicker: mikado isn’t in the Emperor’s official title toolkit. Unlike “Tennō,” which means Emperor, or the Westernized “Emperor of Japan,” it’s a respectful, indirect reference. Somewhat like how in English one might say “the Crown” instead of the monarch. The precise meaning hinges on context and time period.

This indirectness reflects Japanese cultural norms about respect, formality, and even secrecy surrounding the Emperor’s person. Using “Mikado” skirted the social taboos of naming the Emperor directly in some contexts.

Lessons From the Linguistic Journey

So, what does all this historical and linguistic journey teach us?

- Respect speaks volumes. The prefix “mi-” isn’t decoration; it’s reverence dripping from every syllable.

- Toponymy matters. Places can stand for people, especially in hierarchical societies. The Emperor and his palace blur into a single symbol.

- Language evolves. Words can start abstract, become metaphorical, and finally go literal. With mikado, this stretched across centuries.

- Literature is a mirror. Texts from different eras reflect changing perceptions of the Emperor and his representation.

Can We Find Practical Insight Today?

If modern readers or students of Japanese history want to get “under the hood” of imperial terminology, recognizing the journey of mikado offers rich insight into Japan’s cultural respect for its monarch. It shows how language shapes and is shaped by politics, social structure, and poetic tradition.

Also, if you’re diving into classical Japanese literature, spotting the word mikado can give clues about the text’s dating and the author’s intent. Is it the gate? The court? Or the Emperor himself? Context is king—or should we say, Emperor!

Final Thoughts: The Emperor and the “Mikado”

While “Mikado” may sound like an official title from the outside, it isn’t. It’s a layered word, steeped in respect and symbolism, that slowly morphed into a common personal shorthand for the Emperor in the 11th century. The path runs from 8th-century kanji marks and poetic allusions, through metaphorical palace gates, to 1062 literary clarity.

Next time you hear “Mikado,” remember you’re hearing centuries of linguistic evolution designed to revere but not name, to hint but not declare, to respect but avoid direct address. And that’s a story that outshines many official titles combined.

When did the Emperor of Japan first start to be called “Mikado”?

The term “Mikado” began appearing in texts by the 8th century, but mostly as a metaphor for the palace or court. Clear personal reference to the Emperor as “Mikado” emerged around the 11th century, especially by 1062.

Was “Mikado” originally an official title for the Emperor?

No, “Mikado” is not an official title. It was a respectful word used indirectly to refer to the Emperor, often meaning “gate” or the palace rather than the person himself.

What is the origin and meaning of the word “Mikado”?

“Mikado” combines the respectful prefix “mi-” and a character for “gate.” It figuratively referred to the Emperor’s palace or court. Kanji for “Mikado” also linked to “Son of Heaven,” showing its symbolic nature.

Are there early examples where “Mikado” clearly meant the Emperor personally?

Yes, one poem from the 9th century Man’yōshū (poem 4480) seems to use “Mikado” as a direct personal reference to the Emperor, but such clear usage was rare before the 11th century.

When did “Mikado” become commonly used to mean the Emperor himself?

By the mid-11th century, texts like the Hamamatsu chūnagon monogatari (1062) frequently used “Mikado” clearly to mean the Emperor, marking its common personal use in literature.