The capital of China is called Beijing instead of Peking because of a shift in transliteration systems from older methods to the modern pinyin system. “Peking” originates from older transliteration systems, mainly the Postal Map system and Wade-Giles, used in the 19th and early 20th centuries. In contrast, “Beijing” is derived from pinyin, a standardized system introduced by the People’s Republic of China (PRC) in the 1950s.

The older Wade-Giles and Postal systems rendered the capital’s name as “Peking.” This spelling reflects historical attempts to approximate Chinese sounds using the English alphabet. However, these systems did not represent Mandarin pronunciation accurately and often caused confusion.

The PRC developed pinyin to provide a simpler and more consistent way to write Chinese words in the Latin alphabet. It helped unify Chinese language education and improved pronunciation learning for both native speakers and foreigners. Pinyin aligns more closely with the modern standard Mandarin pronunciation. For example, the Mandarin pronunciation begins with a “B” sound, not a “P.”

As China began to open to the world in the 1970s through the 1990s, the government promoted pinyin as the official romanization system. This adoption helped foreign governments, media, and educators standardize place names and personal names across the globe.

Both “Peking” and “Beijing” represent the same Chinese characters 北京, meaning “Northern Capital.” The difference lies purely in the transliteration method. Today, almost all Chinese people and official documents use pinyin exclusively, making “Beijing” the accepted global name.

- “Peking” comes from older postal and Wade-Giles transliteration systems.

- “Beijing” uses pinyin, created by the PRC in the 1950s.

- Pinyin is easier to learn and more phonetically accurate.

- China officially adopted pinyin to standardize spelling and pronunciation.

- “Beijing” and “Peking” are different romanizations of the same Chinese name.

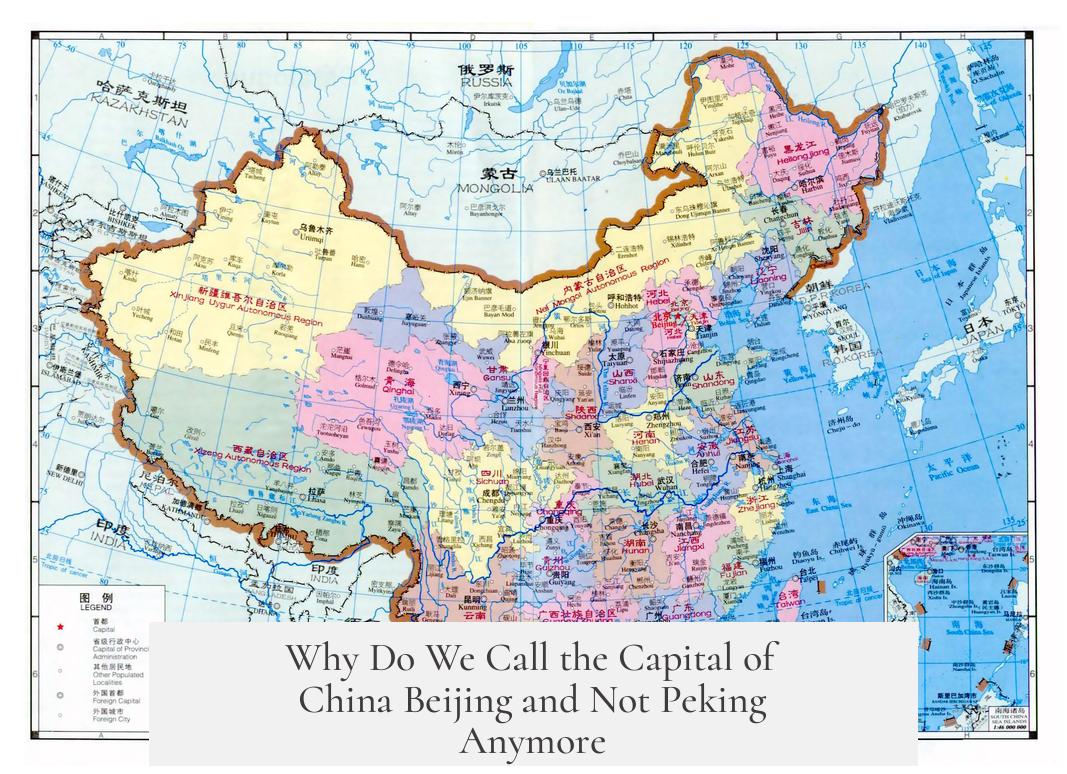

Why Do We Call the Capital of China Beijing and Not Peking Anymore?

The answer is both simple and tied deeply to language evolution and politics: Beijing and Peking are the same name, just rendered through different transliteration systems. But why the shift? Let’s break it down.

People often get confused when they hear both “Beijing” and “Peking” referring to China’s capital. The key lies in how Chinese characters get converted into the English alphabet, a process called transliteration. It turns out, the system used to do this has changed over the years.

The Tale of Two Transliteration Systems

To understand why we moved from Peking to Beijing, we need a short dose of history. The name Peking comes from a system called the Postal Map transliteration, which was popular in the 19th and early 20th centuries. This system pulled from earlier methods like the Wade-Giles transliteration. Wade-Giles was developed in the 19th century by British scholars who were among the first Westerners to seriously study Chinese. Sounds fancy, right?

Under Wade-Giles and Postal Map systems, the Chinese name 北京 (which literally means “Northern Capital”) was rendered as “Peking.” It became the international standard for many decades. So, when early Western travelers, diplomats, or cartographers wrote about China’s capital, they used “Peking.”

Enter the Modern Hero: Pinyin

But in the 1950s, the newly formed People’s Republic of China rolled out a fresh new system called pinyin. Now, pinyin was no ordinary alphabet soup; it was designed to be easier to learn, pronounce, and use for modern education. Basically, it was a fresh coat of paint on how Chinese sounds hit the English ears. Compared to those clunky older systems, pinyin is like switching from Morse code to a smooth Spotify playlist.

With pinyin, 北京 turned into Beijing — which, for the record, is much closer to how local Mandarin speakers pronounce it today. Pronunciation drift and regional accents had made older transliterations less accurate. Pinyin helps everyone speak it the way locals do.

Was this just a fancy linguistic update? Not quite. Pinyin also became a symbol of China’s push to unify language education across the vast country. It’s no surprise then, that almost all Chinese people and the official government media exclusively use pinyin now.

Why Stop Using Peking? Why Not Both?

Good question. The shift from Peking to Beijing wasn’t immediate, and older names don’t disappear overnight. The “Peking” label still appears in places like “Peking University” or “Peking duck,” relics of history that refuse to vanish.

However, as China opened its doors to the world in the 1970s through the 1990s, embracing modernization and global trade, clarity became king. Using pinyin made more sense internationally—it’s the spelling taught in schools, found on road signs, in passports, and government documents.

Imagine the chaos if official documents said “Peking” but everyone else called it “Beijing.” Consistency helps with diplomacy, trade, and education—even for things as routine as flight tickets.

Same Name, Different Spelling

The crux: Beijing and Peking are two transliterations of the exact same name. Like spelling “color” vs. “colour,” the divergence happens because of who did the spelling and when.

This means, linguistically speaking, no one is “wrong” when referencing Peking with historical context. But “Beijing” reigns supreme as the modern and officially recognized spelling worldwide.

What Does This Mean for Travelers and Learners?

- If you’re booking flights, using “Beijing” will get you there safely.

- “Peking” still shows up in historical texts, older directories, and some traditional businesses—you might visit Peking University or savor Peking duck, and that’s absolutely normal.

- When learning Mandarin, focus on pinyin—it’s the key to connecting with modern Chinese language learning and culture.

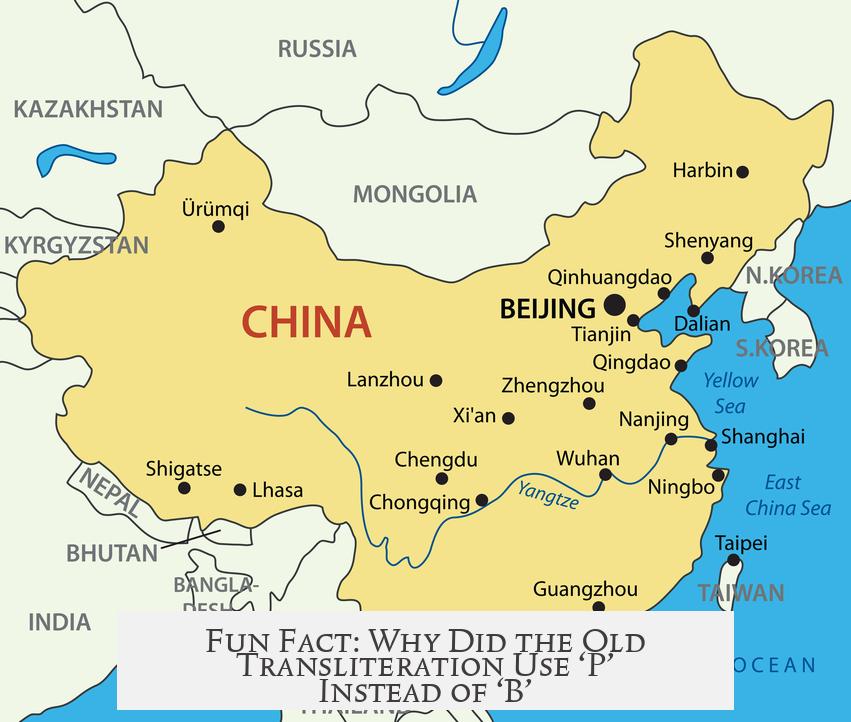

Fun Fact: Why Did the Old Transliteration Use ‘P’ Instead of ‘B’?

This is less about mispronunciation and more to do with how the older systems captured aspirated sounds. The Chinese “B” sound in Beijing is unvoiced and slightly aspirated, which Wade-Giles often marked with a “P.” Confusing? Sure. But pinyin simplifies this by matching the current Mandarin pronunciation more closely.

Conclusion: The Name Change Reflects More Than Just Letters

This seemingly small shift from Peking to Beijing tells a layered story. It’s about linguistic evolution, cultural pride, and China stepping confidently onto the world stage with a standardized, easy-to-learn language system. It also highlights how language standards can shift over time, bringing clarity and consistency but sometimes leaving old habits lingering in conversation, cuisine, and university names.

So next time someone wonders why we call the Chinese capital Beijing instead of Peking, you’ll know it’s all about embracing the modern way—a standardized, clearer, and more accurate representation of the city’s name, anchored in political and educational reforms.

Language isn’t static. Neither is history. Names evolve, and Beijing’s story proves it.