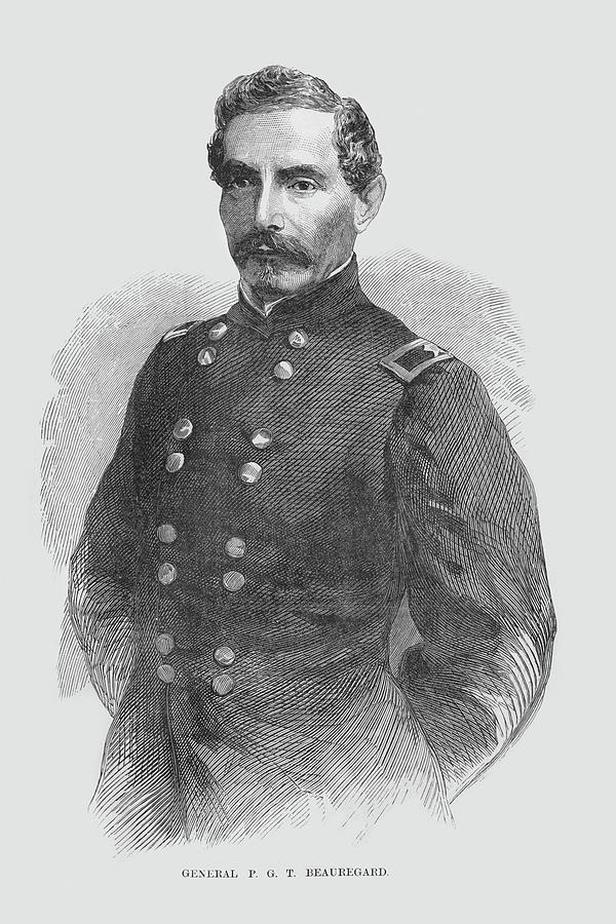

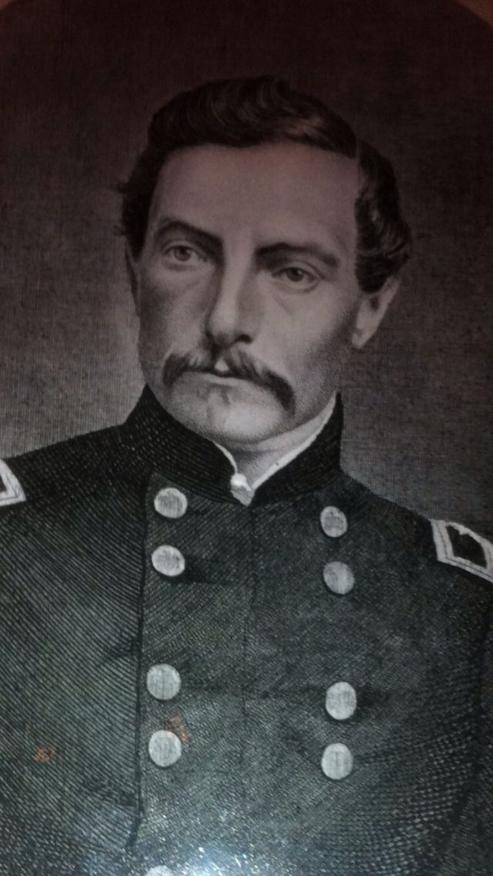

Confederate General P.G.T. Beauregard harbored deep animosity toward Jefferson Davis due to clashes rooted in personality, military disagreements, and political sidelining throughout the Civil War.

Beauregard and Davis shared strong egos and viewed themselves as military experts. Both men lacked humility, but Beauregard arguably had more justification for his confidence. Their backgrounds also set them apart; Beauregard’s Catholic faith and French-Creole heritage distinguished him from the predominantly Protestant, Anglo-Saxon Confederate leadership, fueling cultural and social friction within the high command.

Their hostility began early, notably after the First Battle of Bull Run in 1861. Beauregard blamed Davis for the failure to pursue the retreating Union forces, believing this missed chance cost the Confederacy an early end to the war. Beauregard also took the unprecedented step of offering military advice to Davis, who rejected it and responded by marginalizing Beauregard. To reduce any influence Beauregard wielded, Davis reassigned him westward as second-in-command under Albert Sidney Johnston, diminishing Beauregard’s standing.

The Battle of Shiloh in 1862 exacerbated tensions. Johnston, a close friend of Davis and considered the Confederacy’s leading general, died in the battle. Davis publicly blamed Beauregard for the defeat, portraying Johnston as the cause of potential victory had he survived. This scapegoating stripped Beauregard of field command. Subsequently, Beauregard was relegated to less influential commands in Charleston and Petersburg. Despite performing competently there, the stain of Shiloh and Davis’s criticism lingered.

Later, after the pivotal fall of Atlanta in 1864, Davis sent Beauregard back to the Western theater to halt Sherman’s march. However, Davis withheld real operational command authority from Beauregard over the Confederate forces in the region. The task was virtually impossible, given Sherman’s overwhelming strength and momentum. When Sherman advanced largely unopposed through Georgia and the Carolinas, Beauregard bore the brunt of the blame.

Additionally, Beauregard was technically in command during General John Bell Hood’s disastrous campaigns at Franklin and Nashville, adding to his association with strategic failures in the Western theater. These defeats further intensified Beauregard’s bitterness toward Davis’s leadership decisions and judgment.

After the war, Beauregard’s reputation suffered. His involvement with the Louisiana Lottery and public endorsement of African-American suffrage alienated many Southern contemporaries. The Lost Cause mythology gained traction and portrayed Beauregard unfavorably—focusing on his responsibility for Shiloh’s defeat while minimizing his other achievements. This narrative cemented his status as a controversial and sidelined figure in postwar Southern history.

| Aspect | Cause of Hate |

|---|---|

| Personality Differences | Egos clashed; Beauregard’s unique background set him apart |

| First Battle of Bull Run | Beauregard blamed Davis for missed opportunity; advice rejected |

| Battle of Shiloh | Davis scapegoated Beauregard, favored Johnston; Beauregard removed from command |

| Western Theater and Sherman’s March | Davis assigned impossible task with limited authority; Beauregard blamed for failures |

| Post-War Legacy | Unpopular political views; Lost Cause myth damaged reputation |

- Beauregard and Davis had conflicting egos and cultural differences.

- Beauregard blamed Davis for missed tactical chances early in the war.

- Davis publicly blamed Beauregard for Shiloh defeat, favoring friends.

- Davis gave Beauregard impossible military tasks with no sufficient authority.

- Post-war perceptions hurt Beauregard’s legacy in the South.

Why Did Confederate General P.G.T. Beauregard Hate Jefferson Davis?

Confederate General P.G.T. Beauregard’s hatred for Jefferson Davis boils down to clashing egos, bruised pride, and a cascade of blame-shifting that made Beauregard feel undervalued and unfairly targeted throughout the Civil War. Let’s unravel the tale behind one of the Confederacy’s most famous grudges. It involves big personalities, missed opportunities, and a tumultuous relationship marked by mutual disdain masked as respect.

First, it’s essential to know that both men were convinced geniuses of the military world, never shuttering their mouths or egos. But—here’s the kicker—Beauregard had more on-field victories to back up his confidence than Davis did, who was, after all, running the Confederate show. Also, Beauregard wasn’t your typical Confederate general. His French-Creole heritage and Catholic faith made him stand out in a sea of mostly white Anglo-Saxon Protestant officers. That cultural difference may have added to the tension simmering beneath their professional clashes.

The Clash Begins: First Bull Run and Early Tensions

Remember the First Battle of Bull Run? It was the Confederates’ debutante ball in war, a messy but surprisingly victorious outing. Beauregard believed the Confederacy could have sealed the deal that day by chasing the retreating Union forces and ending the war quickly. Instead, Davis—who was in charge—ordered restraint.

Here’s where the fireworks start: Beauregard didn’t hold back expressing his frustration. He openly blamed Davis for the failure to pursue the Union army and end the conflict swiftly. Imagine telling your boss what he did wrong during the biggest event of the year. Davis wasn’t thrilled. In fact, he started sidelining Beauregard, sending him west as a second-in-command to Albert Sidney Johnston, another top Confederate general and one of Davis’s personal friends. It was a clear demotion in Beauregard’s eyes.

Shiloh and Scapegoats: The Blame Game Gets Worse

The Battle of Shiloh in 1862 was a tragedy for the Confederates, especially with Johnston’s death early in the fight. Davis had massive respect for Johnston, who was both a great general and his buddy. When things went south, Davis did something classic: he shifted the blame onto Beauregard.

According to Davis, if Johnston had lived, the Confederates would have won at Shiloh. Now, that’s an opinion packed with bias. Beauregard was stripped of significant command responsibilities and shuffled off to quieter theaters like Charleston and Petersburg. While Beauregard still fought well, he was essentially put out to pasture, which festered his hatred for Davis. Being scapegoated for a defeat while sidelined cuts deep—even for a man with his ego.

Sherman’s March and A No-Win Assignment

In the later stages of the war, after Atlanta fell, Davis gave Beauregard an impossible job: stop General Sherman’s march through Georgia and the Carolinas. Sounds straightforward, right? Wrong. Davis assigned Beauregard to the Western theater but didn’t give him any real power over the Confederate armies unless he was right there with them. That’s like giving someone the job of stopping a freight train with a feather.

Unsurprisingly, Sherman tore through the South with ease. Beauregard was blamed for the disasters at Franklin and Nashville, even though his control was limited and compromised. Being held responsible for failures yet stripped of authority deepened Beauregard’s loathing of Davis.

Post-War Fallout and Lost Cause Mythos

When the war ended, Beauregard’s troubles didn’t stop. He involved himself in the controversial Louisiana Lottery and even supported African-American suffrage—two moves that soured many Southern whites who idolized Confederate leaders but embraced the Lost Cause myth. This myth conveniently overlooked Beauregard’s successes and fixated on his supposed failings.

His support for rights for Black Americans was a courageous stance in a place and time where such views were frowned upon. But it didn’t win him any popularity contests, especially among the white Southern elite who controlled the narrative.

The Lost Cause movement painted Beauregard as a figure responsible for Confederate setbacks rather than a brilliant tactician with a flawed, complicated history. Davis’s narrative dominated, overshadowing Beauregard’s record and fueling the long-standing bitterness between the two.

A Tale of Egos, Power, and Politics

So, what’s the unique takeaway here? Beauregard hated Jefferson Davis because of personal slights, professional clashes, and political rivalries rooted deeply in their contrasting backgrounds and styles. Beauregard’s legitimate military talent and outspokenness clashed with Davis’s leadership style, which often involved protecting allies like Johnston and blaming those he distrusted.

Is this just a tale of two egos colliding? Yes, but it also highlights how personal dynamics and politics can shape—and sometimes sabotage—the fate of nations. Can you imagine how different Civil War history might have been if these two had found common ground?

For anyone intrigued by military history and leadership, Beauregard’s story offers a lesson: half the battle is winning over your peers and superiors, not just the enemy. And sometimes, cultural differences and policy decisions matter as much as battlefield tactics.

In the end, Beauregard and Davis’s feud is a textbook example of how personal animosities and political gamesmanship can influence history’s course—sometimes with deadly consequences.