Catholics and Protestants have different versions of the Lord’s Prayer primarily due to variations in biblical manuscripts, historical translation choices, and liturgical traditions. The key difference centers on the inclusion or omission of the doxology phrase: “For thine is the kingdom, and the power, and the glory, forever. Amen.” This phrase appears in many Protestant versions but is generally absent from Catholic textual translations and prayers.

The Lord’s Prayer is recorded twice in the New Testament: once in the Gospel of Matthew (6:9-13) and once in the Gospel of Luke (11:2-4). Matthew’s version is considered the most common form used in Christian liturgy. However, Matthew’s manuscripts themselves show two versions of the prayer—one shorter without the doxology and one longer including it.

The doxology at the end is not found in the earliest and most reliable Greek manuscripts, such as the Codex Vaticanus and Codex Sinaiticus from the 4th century, which are part of the Alexandrian text-type. These older manuscripts reflect a version of the Lord’s Prayer without the concluding phrase. Catholic biblical translations, such as the Douay-Rheims, the Revised Standard Version Catholic Edition, and the New American Bible, follow these earlier texts. This is why Catholic prayers often omit the doxology in the Lord’s Prayer itself, though the Catholic Mass includes this phrase as a separate doxology after the prayer.

In contrast, many Protestant Bibles are based on the Textus Receptus, a Greek New Testament compilation from the early 16th century. This text included the doxology phrase, and it was consequently incorporated into Protestant translations like the King James Version (1611). The inclusion of the doxology became standard in English-speaking Protestant liturgy, especially through the Anglican Book of Common Prayer (from 1662 onward). Protestants, therefore, commonly recite the longer version ending with the doxology.

This difference partly arises from the historical contexts of translation. Jerome’s Latin Vulgate, used by Catholics since the 4th century, reflects the shorter form without the doxology. Protestant reformers in the 16th century preferred translations using the Textus Receptus, which contained the doxology, aligning their version with popular vernacular Bibles of the time.

The history of manuscript copying helps explain how differences arose. Before printing, all biblical texts were copied by hand. Scribal notes or marginal additions sometimes found their way into the main text during successive copies. The doxology may have begun as a marginal doxology from early Christian documents, like the Didache, and eventually was adopted into some manuscripts as a formal ending. Over time, these versions gained prominence in specific manuscript traditions, influencing translations and liturgical practices.

Liturgical tradition also affects usage. Eastern Christian rites, including Eastern Orthodox and Eastern Catholic Churches, maintain the doxology in their liturgies. Western liturgies followed the shorter form but reintroduced the doxology in Mass prayers after the Second Vatican Council, likely influenced by Eastern Fathers. Thus, the doxology is present in Catholic worship but not embedded in the standard textual prayer itself.

- The Lord’s Prayer exists in two scriptural versions: Matthew and Luke.

- The doxology “For thine is the kingdom…” appears in some manuscripts, not in the earliest or most reliable ones.

- Catholics rely on older manuscripts (Alexandrian text-type) omitting the doxology in scripture.

- Protestants often use the Textus Receptus (Byzantine text-type), which includes the doxology.

- Translation history shows Jerome’s Vulgate with the shorter prayer and Protestant Bibles with the longer one.

- Liturgical traditions differ: Catholics include the doxology in Mass but not in the basic prayer form.

- Manuscript copying errors and traditions led to textual variations over centuries.

In summary, the difference between Catholic and Protestant versions of the Lord’s Prayer stems from textual variations in manuscript traditions, translation choices influenced by historical contexts, and established liturgical customs. The doxology’s presence or absence marks the key distinction, reflecting deep-rooted scholarly and ecclesiastical decisions rather than doctrinal disputes over the prayer’s core meaning.

Why Do Catholics and Protestants Have a Different Version of the Lord’s Prayer?

In short: Catholics and Protestants have different versions of the Lord’s Prayer mainly because of variations in ancient manuscripts, translating traditions, and the presence or absence of a certain doxology at the end of the prayer. The story is a fascinating tangle of history, textual scholarship, and liturgical evolution. Let’s unravel it!

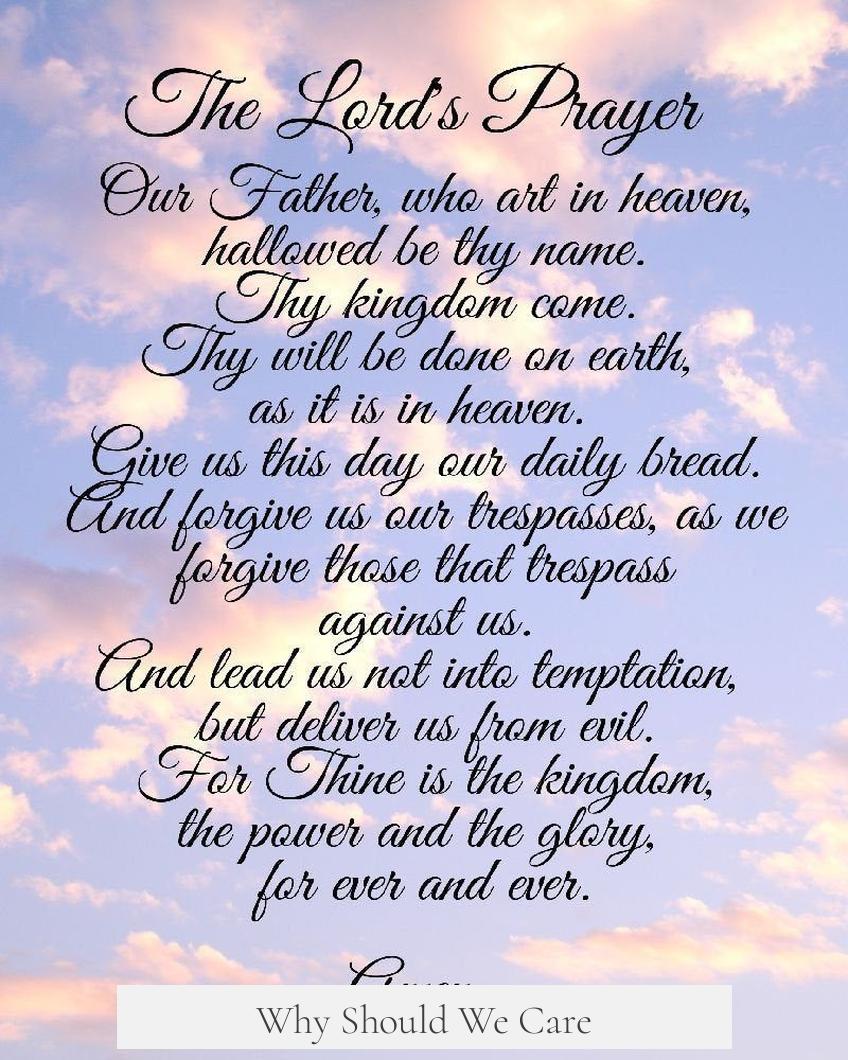

Most people can rattle off the Lord’s Prayer — “Our Father who art in heaven…” — without missing a beat. But if you’ve ever compared the Catholic and Protestant versions side-by-side, you might notice a subtle difference: the Protestants often include the phrase, “For thine is the kingdom, and the power, and the glory, for ever. Amen.” Catholics typically don’t include this in the prayer itself but do say it liturgically. What’s going on?

Two Versions of the Lord’s Prayer in the Bible

The Bible itself offers two versions of the Lord’s Prayer. The longer one is found in Matthew 6:9-13, while a shorter one appears in Luke 11:2-4. Conveniently, the doxology—the “For thine is the kingdom…” phrase—is absent in Luke’s shorter version.

Interestingly, the “Matthew version” has two manuscript variants: an earlier short form and a later expanded form that added the doxology. That little ending is the crux of the difference between Catholic and Protestant usage.

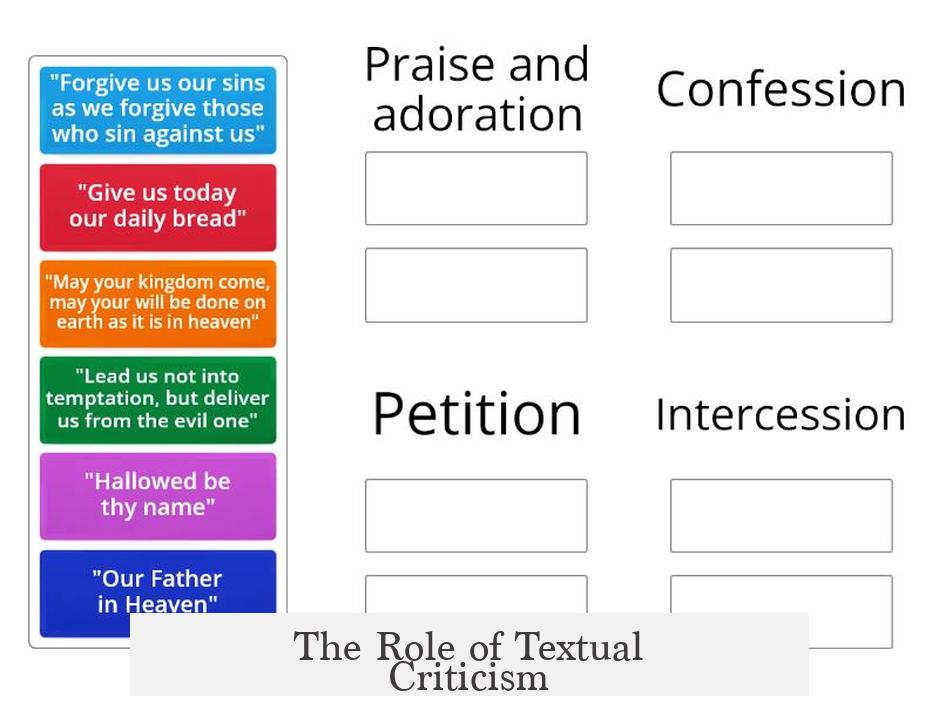

The Mighty Doxology

So, what exactly is a doxology? It’s a short praise to God that often finishes prayers and hymns. The doxology in the Lord’s Prayer—“For thine is the kingdom, and the power, and the glory, for ever. Amen.”—is one of the most famous.

Among English-speaking Protestants, this doxology became standard, mainly because it’s in the King James Version (KJV) of the Bible, which was hugely influential. The Anglican Church included it in their Book of Common Prayer, specifically in the 1662 edition, cementing its place in Protestant tradition.

Meanwhile, Catholic Bible translations—like the Douay Rheims, the Revised Standard Version Catholic Edition, and the New American Bible—don’t include the doxology in the prayer text. The Catholic liturgy, however, does say it aloud during Mass to round off the prayer.

The Manuscript Game: Alexandrian vs. Byzantine

Here’s where it gets a bit like detective work. Ancient biblical manuscripts come in families or “text-types.” Two major ones are Alexandrian and Byzantine.

Catholics have traditionally used older, Alexandrian manuscripts, such as the 4th-century Codex Vaticanus. These texts usually have the shorter version of the Lord’s Prayer without the doxology. St. Jerome’s Latin Vulgate, a cornerstone of Catholic Scripture dating from the 4th/5th century, follows these older manuscripts and doesn’t include the doxology in the prayer proper.

Protestants, in contrast, often trace their Bible translations back to the Byzantine text-type, which includes the longer version with the doxology. A famous example is the 5th-century Codex Washingtonianus. The early 16th-century Greek edition called the Textus Receptus, formed mostly from Byzantine texts, included the doxology and thus shaped Protestant translations like the Tyndale Bible (1534) and the KJV (1611).

The Role of Textual Criticism

As scholars examined manuscripts over centuries, they developed textual criticism—a science of comparing copies to find the earliest and most trustworthy original text.

This process revealed that the earliest manuscripts, including Codex Sinaiticus and Codex Vaticanus, contain the shorter Lord’s Prayer without the doxology. The doxology likely appeared later, possibly as a scribal addition or a liturgical flourish that was mistakenly inserted into some manuscripts as part of the prayer.

Given this, most modern Catholic Bible translations follow these older manuscripts and leave the doxology out of the prayer itself. Protestants face a mixed picture but often retain the doxology because of its historical usage in popular translations and worship traditions.

Historical Translation Context

The Catholic Bible’s backbone—the Vulgate—is a late 4th-century Latin translation. Jerome, who made the Vulgate, worked from Greek texts aligned with the Alexandrian tradition, hence the short version of the prayer.

The Reformation turned the Bible into a vernacular weapon for Protestant leaders eager to make Scripture accessible. Erasmus’ 1516 Greek New Testament, based on Byzantine manuscripts, included the longer form. His work became the foundation for key Protestant translations like the KJV. So, for Protestants, the doxology was inherited from the textual sources they prioritized.

Liturgical and Traditional Influence

This isn’t just a matter of ancient manuscripts on a shelf. The Lord’s Prayer has been a staple of Christian worship and catechesis since at least the 1st century. Early Christian documents like the Didache contain evidence of doxological endings to the prayer, indicating early liturgical use that shapes our modern traditions.

Eastern Orthodox and Eastern Catholic Churches preserve the doxology in their liturgies, reflecting continuity with ancient Christian practice. Western Catholics generally avoided it in the liturgical prayer until the Second Vatican Council (1962-1965), when Eastern influence helped reintroduce the doxology into the Mass’s ordinary form, though still not in the prayer said privately.

In contrast, the Anglican 1662 Book of Common Prayer made the longer version official, deeply embedding it in Protestant worship. For many Protestants, suddenly dropping the doxology feels like an incomplete prayer—a bit like leaving the finale out of a symphony.

How Scribal Habits Changed the Text

It sounds a bit hilarious, but some of this boils down to ancient copyists misinterpreting notes at the bottom of manuscripts. Imagine a scribe seeing a side note praising God, then mistakenly copying it into the main text of the Lord’s Prayer. By the time multiple copies of this version existed, it spread like wildfire, becoming standard in certain traditions.

This human error reminds us that the Bible’s transmission is a living history, shaped by the people who treasured it and, sometimes, goofed a bit along the way.

Why Should We Care?

You might wonder why it matters if one tradition says, “…for thine is the kingdom, and the power, and the glory…” and the other doesn’t. Does it change the prayer or faith? Not really.

Both versions honor God and offer a pathway to spiritual connection. The differences highlight how communities develop side-by-side, guided by faith, history, and culture.

Knowing these differences enriches our understanding of Christian heritage and shows how sacred texts evolve in human hands. Plus, it can be a fun trivia point at church picnics.

Practical Tips for Readers and Worshipers

- If you’re new to either tradition: Expect some variation in the Lord’s Prayer text—it’s a normal part of Christian diversity.

- Want to compare versions? Look up Matthew 6:9-13 in different Bible translations to spot differences.

- Feel weird about skipping the doxology? Remember Catholics include it in the Mass, just not always in private prayers.

- Interested in textual history? Explore resources on biblical manuscripts like Codex Vaticanus or Textus Receptus for a deep dive.

At its heart, the Lord’s Prayer reminds all Christians of their shared relationship with God. Whether you end yours with or without the doxology, you’re joining millions of voices echoing the prayer Jesus himself taught.

Final Thought

Isn’t it fascinating that a few words written or omitted centuries ago can shape centuries of worship? The story of the Lord’s Prayer differences reveals the amazing journey of the Christian Bible across languages, lands, and lives.

So the next time you recite the Lord’s Prayer—Catholic or Protestant—know you’re part of a rich historical epic. And, maybe, give a little nod to those scribes who, no doubt with good intentions, added flavor to a timeless prayer.

1. Why do Catholics and Protestants include or omit the doxology in the Lord’s Prayer?

The doxology (“For thine is the kingdom…”) is included by most Protestants because it appears in later Greek manuscripts and the King James Bible. Catholics follow earlier manuscripts and Jerome’s Latin Vulgate, which omit it in the prayer itself but include it in Mass.

2. How do manuscript differences impact the versions of the Lord’s Prayer?

Catholics rely on earlier Alexandrian manuscripts that lack the doxology. Protestants often use later Byzantine texts containing it. These textual traditions affected Bible translations and thus the prayer’s wording in each tradition.

3. Did historical Bible translations influence the prayer’s variations?

Yes. Jerome’s 4th-century Vulgate used the short prayer without the doxology. Later Protestant Bibles, like Erasmus’s Greek New Testament and the King James Version, included the doxology, shaping Protestant tradition.

4. Is the doxology part of Catholic liturgy though not in their Bible versions?

Yes. While Catholic Bible translations omit the doxology within the Lord’s Prayer, it is said aloud during Mass after the prayer, maintaining its traditional place in worship.

5. Why do Eastern Orthodox Christians have a unique stance on the Lord’s Prayer’s doxology?

The Greek Orthodox liturgy includes the doxology, but their scriptural translations vary. This reflects the mixture of textual traditions and liturgical practices preserved in Eastern Christianity.