We know Confucius was a real historical figure, supported by multiple independent sources from the Warring States period. These sources consistently affirm his existence and allow scholars to attribute his teachings with confidence. Unlike some other ancient figures, Confucius’s historicity is widely accepted in academic circles.

His main ideas come from the Analects, a collection of sayings and discussions recorded by his disciples. These texts, however, were compiled over many centuries, not written directly by Confucius himself. This complicates the authenticity of the exact words and ideas attributed to him. Scholars doubt that the Analects represent a verbatim account of Confucius’s sayings. Instead, they likely reflect interpretive layers added by later Confucian scholars.

Transmission of these teachings was oral for a significant period. This means the original content passed through many retellings before being compiled. Due to this, it is impossible to establish a fully reliable chain of narration tracing back to Confucius directly. This issue mirrors concerns in other traditions about oral transmission reliability.

Comparing Confucius to other historical or semi-mythical figures helps clarify what we know. For example, the Tao Te Ching, attributed to Lao-Tsu, lacks evidence that it originated from a single person. Similarly, the Art of War is attributed to Sun Tzu without conclusive proof he was a single historical general. Confucius thus stands apart as a confirmed individual with clear historical evidence.

- Confucius’s existence is well-documented by independent historical sources.

- The Analects are later compilations by disciples, not direct writings of Confucius.

- Oral transmission before compilation limits certainty about original sayings.

- Confucius’s historicity is stronger than that of Lao-Tsu or Sun Tzu.

This understanding shapes modern views on Confucianism and ancient Chinese philosophy. It highlights how ancient texts often blend direct teachings with later interpretations.

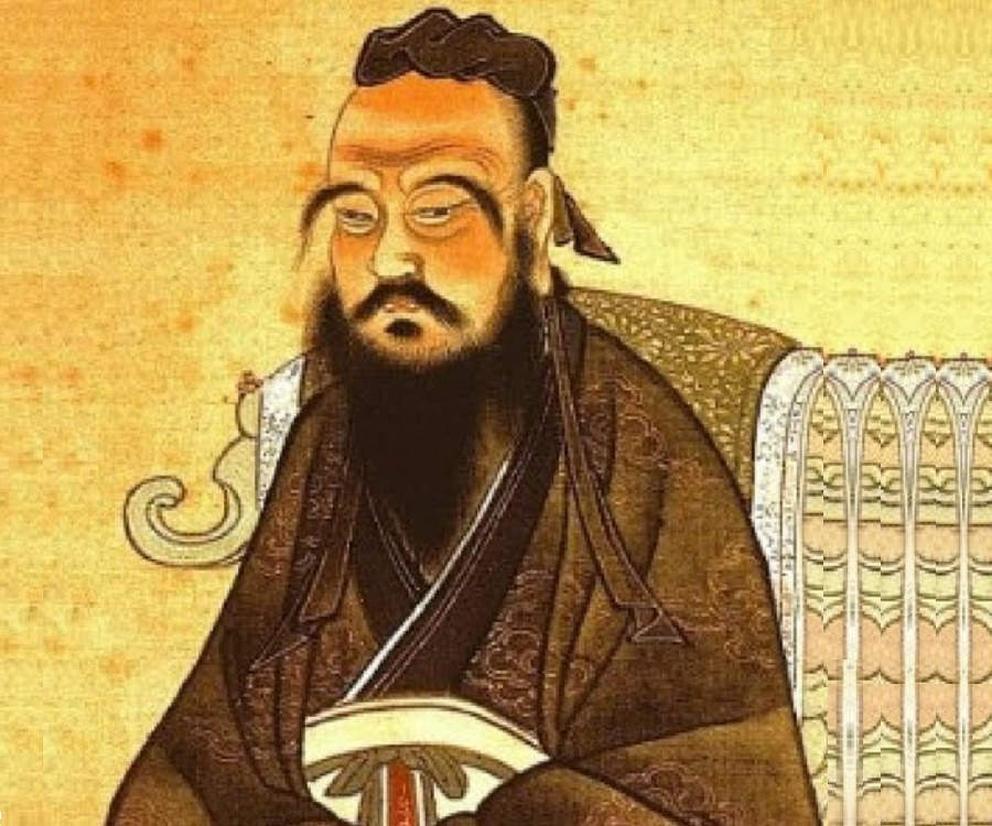

How Much Do We Really Know About Confucius?

Confucius—heralded as one of the greatest ancient Chinese sages—has cast a long shadow across history. But the burning question remains: how much do we really know about him? Is he a simple historical figure, or more myth than man? Let’s peel back the layers and dive into what the evidence says.

The Man Behind the Legend: Confirming Confucius’s Existence

First things first: Confucius definitely existed. Multiple independent sources from the Warring States period (roughly 475–221 BCE) corroborate his existence. These documents, coming from different places and times, offer enough consistency for historians to confidently say Confucius was a real person, not just a legend cooked up later.

Compare this to some other famous Chinese figures like Lao-Tsu or Sun Tzu, where the waters get murky. For Lao-Tsu, the Tao Te Ching is traditionally attributed to him, but evidence suggests it might be a patchwork of works by multiple authors rather than a single mind. Similarly, Sun Tzu, credited with “The Art of War,” is more a shadowy, possibly composite figure without solid proof there was one general behind the entire text.

For Confucius, however, scholars align: he’s a documented historical individual, which means the stories and teachings tied to his name can at least get off the ground factually.

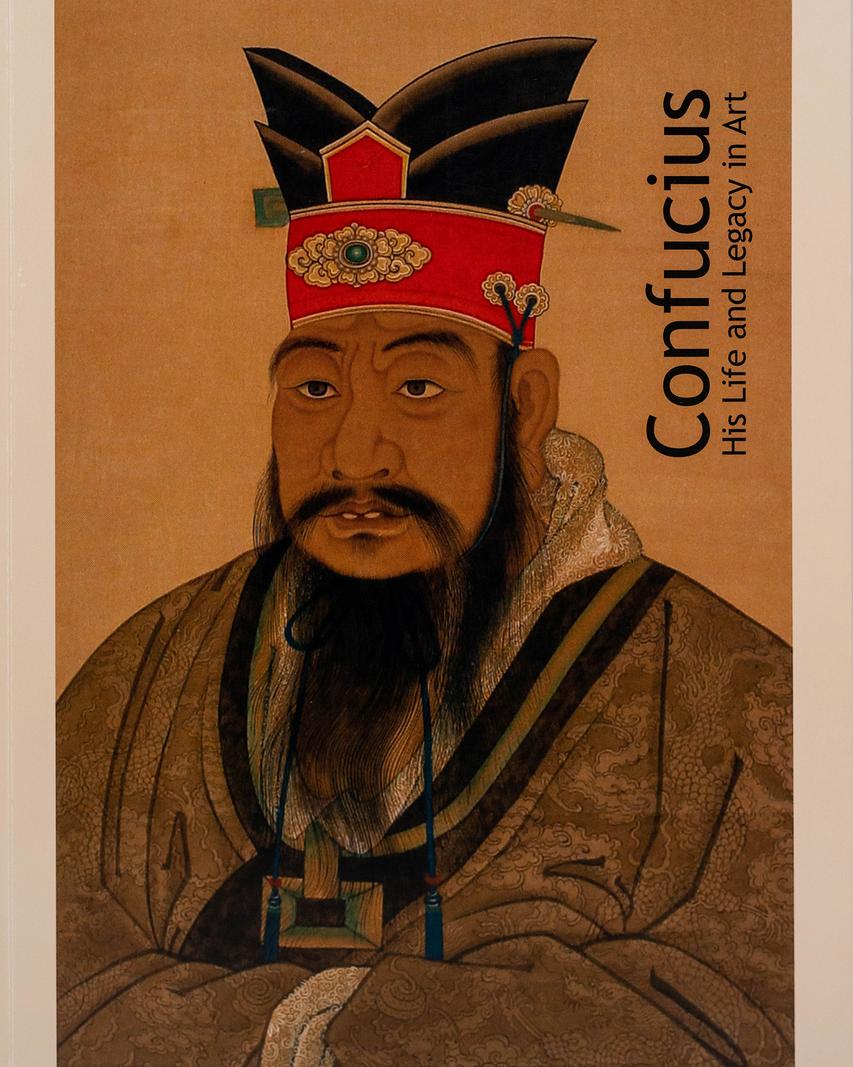

What About the Analects? Authentic Sayings or Later Interpretations?

Now, hold your horses before declaring victory! While Confucius certainly lived, his famous sayings aren’t direct quotations scribbled by his own hand. The Analects—arguably his most famous work—weren’t penned by Confucius himself. They are collections of his disciples’ teachings and thoughts gathered over centuries.

Think of the Analects like a group scrapbook made by fans after the concert. It captures the spirit but might include some overzealous embellishments.

Chinese scholars past and present haven’t seriously claimed these texts to be exact transcripts of Confucius’s words. Instead, these sayings are more like interpretations filtered through generations of Confucian academics who influenced their tone and content. So, if you’re looking for Confucius’s verbatim thoughts, you might be chasing shadows.

The Challenges of Oral Transmission Over Time

Before someone says “Well, let’s verify by tracing the chain of narrations!” be warned: that’s a tall order and, frankly, unacademic here.

Oral traditions played a huge role in passing down Confucius’s teachings before they were written. Unfortunately, no reliable chain of narration exists from that period onward—unlike in other religious or philosophical traditions where meticulous oral tracing occurs. Rebuilding such a chain backward in time is called reverse chronological engineering, which modern scholars frown upon because it relies on assumptions rather than solid proof.

This means the Analects and other Confucian texts, being “word of mouth” legacies, are inherently filters of cultural memory rather than pure, direct transmissions. Over the centuries, the teachings probably evolved to suit changing values, political needs, and educational goals.

So, How Does Confucius Stack Up Against Other Ancient Figures?

Interestingly, Confucius’s historical footprint is clearer than that of some of his contemporaries or near contemporaries. While Lao-Tsu’s authorship of the Tao Te Ching is murky, and Sun Tzu’s precise historical identity remains debated, there is a scholarly consensus on Confucius’s real-life identity. That alone sets him apart.

In fact, this consensus is helpful because it anchors Confucianism in a genuine human life, allowing us to explore his philosophy with the knowledge that it’s not myth but rooted in at least one authentic voice.

What Does This Mean for Modern Readers?

If you’re a fan of wisdom from the East, or you’re studying Confucius’s legacy, here’s a quick takeaway: Confucius lived and shaped ideas directly or indirectly influencing billions. But his “voice” that we hear today is a chorus of disciples, editors, and centuries of thinkers who embellished and adapted his core teachings.

This nuance doesn’t diminish the value of Confucius’s ideas. Instead, it invites a richer engagement. When you read the Analects, you’re hearing a tradition—not a pure personal diary.

Want to get closer to the “real Confucius”? Consider cross-referencing texts from that era, examining various historical records from the Warring States period, and understanding the broader sociopolitical context that shaped his teachings.

Final Thoughts: The Mystery and the Man

Confucius remains one of the best-documented ancient figures in Chinese philosophy, but the exact contours of his voice and thoughts are obscured by time. That’s common for all figures living over 2,500 years ago, but the surviving evidence is stronger here than for many others.

Given the complexities, isn’t it fascinating that Confucius is still *so* relevant? His teachings on ethics, governance, and personal conduct resonate even if we can’t chalk them up word-for-word to him. In a way, the mystery adds to the magic. It invites us not just to study history but to join a tradition of interpretation and reflection.

So next time you read a Confucian quote, smile knowingly. You’re reading wisdom shaped by a collective memory—a centuries-old conversation that started with a man who truly walked the earth. And that, in itself, is pretty remarkable.