“Monday Methods: The past is a foreign country” explores how history differs fundamentally from our present, emphasizing that understanding the past requires stepping into an entirely different world. This perspective challenges common views by underscoring the sensory, social, and cultural distance between then and now.

The past feels unfamiliar because people lived in vastly different environments. For example, a medieval peasant experienced minimal sounds aside from nature and work-related noises. Approaching footsteps or the clanking of armor stood out sharply. This contrasts strongly with today’s constant urban noise. Such sensory details highlight how everyday life shaped perceptions and responses. Heavy armor meant status and authority; the sound itself was a signal, unlike modern urban anonymity.

Architecture further defines this foreignness. In medieval cities like Cologne, towering stone cathedrals dominated the skyline. They served as monuments of power and faith, visible miles away. Since most buildings were modest wood structures, these cathedrals announced control and influence before one even entered the city. Castles reinforced this, symbolizing Norman conquest and authority. These landmarks communicated dominance uniquely tied to their era’s social order and technological limits.

The idea that “the past is a foreign country” extends beyond sensory and material culture. It also challenges historical narratives, particularly Eurocentric views. Scholars working on African history stress the importance of indigenous agency. Colonial sources often frame history through the colonizers’ lens, obscuring internal dynamics and downplaying African political complexity. Events were rarely all about European settlers; African kingdoms engaged in their politics independent of colonial influence.

This reexamination revisits conflicts considered simple “brutal attacks” in colonial texts. Indigenous leaders’ actions sometimes reflect strategic consolidation during succession disputes, not erratic violence. Europeans often played incidental roles as observers or opportunistic participants rather than central actors. This perspective reveals the limits of colonial records and urges caution when interpreting history solely from colonizers’ viewpoints.

Moreover, surviving historical sources offer narrow vantage points. Actors in the past cared about their immediate realities, not modern concerns or current historical interests. Their records reflect specific contexts, leaving much unknown or misunderstood. Historians work to expand these perspectives but can only partially reconstruct the broader human experience. The result is an often circumstantial and fragmented view requiring thoughtful analysis.

Understanding historical attitudes also demands avoiding presentism—judging past figures by today’s moral standards. Consider H.P. Lovecraft, who supported aspects of Hitler’s rise due to opposition to Bolshevism and personal biases. By today’s standards, his views appear unacceptable, but they aligned with some prevailing beliefs of his era. His partial support did not equate to unqualified endorsement, and he did not live to see the full extent of Nazi atrocities. Recognizing this nuance highlights the complexity of historical figures’ motivations and contexts.

This insight reminds researchers to engage deeply with primary sources, such as Lovecraft’s extensive letters, to understand how views evolved over time. Surface-level judgments overlook factors shaping opinions and limit richer comprehension of history’s complexities.

Mythology represents another dimension of the past as a foreign country. Myths communicate values through metaphor and allegory, making extraordinary experiences relatable. Ancient stories personify virtues and vices in symbolic characters. Gods and heroes represent ideals or fears, not literal beings, reflecting how early cultures framed their understanding of existence and morality.

Language and metaphor in mythology serve as universal tools for communication, embedding cultural norms and lessons in engaging narratives. These symbolic systems allowed societies to express difficult concepts and transmit knowledge across generations. Recognizing mythology as a layered, symbolic language helps modern readers grasp how past peoples made sense of their worlds.

- The past differs significantly in sensory experience, social structure, and environment.

- Medieval architecture symbolized power uniquely unlike today’s urban landscape.

- Historical narratives must include indigenous perspectives, challenging Eurocentric biases.

- Sources provide limited views; actors in the past operated under different concerns.

- Avoid presentism to understand historical figures’ views in their time.

- Mythology conveys values through metaphor, shaping cultural understanding.

Monday Methods: The Past Is a Foreign Country

What does it mean when we say “the past is a foreign country”? Simply put, it means the past operates by different rules, senses, and contexts than our present day. Life centuries ago or decades ago isn’t just old; it’s alien—in sights, sounds, and social structures. Dive into history like you’re a tourist exploring an exotic land, not like flipping through a dated photo album. Understanding this mindset helps us make sense of historical events, people, and cultures without forcing our modern views on them.

Let’s unpack this idea together. It’s more than a clever phrase. It’s a conceptual key that opens up a world often misunderstood because we view it through today’s lens.

The Sensory Landscape of the Past

Imagine a medieval village. It’s not exactly buzzing with car horns or smartphone notifications. In fact, the sounds are simple: the clatter of tools, animals stirring nearby, and the wind whispering through open fields. If a rider armed with heavy armor approaches, their metallic steps and clanking armor announce their arrival far before their shadow meets the village gate.

Now, contrast this with a modern city. You likely don’t notice individual footsteps, let alone a single person approaching from miles away amid the urban hum. Back then, sensory experiences framed daily life and social awareness. The lack of noise pollution made every sound a meaningful signal, a message. A stone cathedral seen on a distant hill could dominate your approach to a city, telling any traveler who held power. This architectural dominance shaped social order—no need for tweets or news alerts.

Architecture as Silent Authority

Walk through the streets of Cologne today and admire its giant cathedral. It’s beautiful, no doubt. But in medieval times, the mere sight of such a stone structure from miles away told you who was boss without a single word.

Stone buildings were rare. Most houses were wood and single-story. That cathedral or the imposing Norman castles in England were a visible mark of power — towering symbols that literally and figuratively overshadowed the rest. The past’s landscape was a stage, where stone and timber said, “Respect this place.”

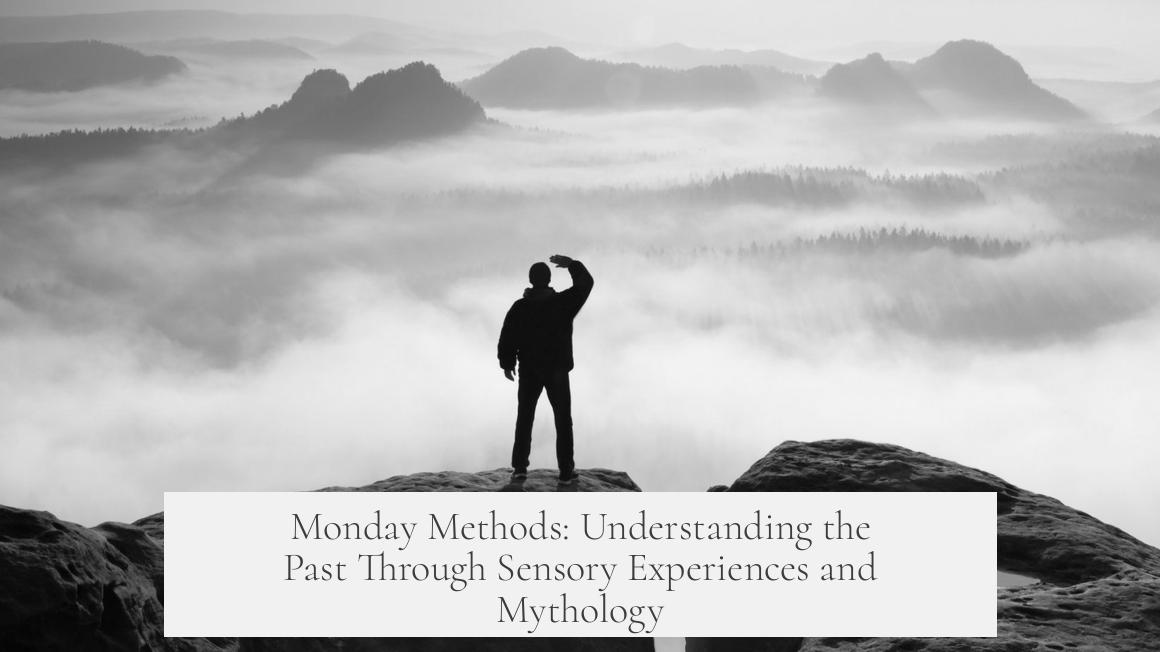

Challenging Eurocentrism: The Past Isn’t Always About Us

Now, here’s where history gets tricky. Too often, historians have focused on European colonizers like they’re the stars of every show. But African history, particularly South Africa’s, reveals a different story. Many historic events weren’t about Europeans at all.

Think about it: most colonial records come from settlers’ perspectives, often biased or incomplete. For instance, what colonialists called “violent brutes” were actually leaders trying to maintain power amid complex rivalries.

One Venda historian points out that European and Boer interpretations missed internal African politics’ nuances. Europeans sometimes played minor roles, not central ones. They were watchers more than actors, peripheral not pivotal.

It’s a reminder: the past doesn’t revolve solely around the colonizers. It’s a bigger, more complicated world. History’s narratives shift when we acknowledge that not all past actions or conflicts centered around Europeans.

Brushing Aside Presentism: Judging by Today’s Standards

We face a common trap in history—judging figures by today’s morals. Take H.P. Lovecraft, the early 20th-century writer. He expressed views that aligned partially with fascist ideals and even supported Hitler’s rise due to opposition to Bolshevism and other reasons. This sounds awful today, and rightly so.

But Lovecraft’s context matters. He lived before the Holocaust’s horrors were known. His prejudices were debated during his lifetime. While today those views are indefensible, back then, they were regrettably common. Ignoring context leads to shallow, unfair critiques. Truly understanding requires digging into all his letters and writings, which span over two dozen volumes.

Learning this is like adjusting a lens to see history in focus—not blurred by our biases.

The Role of Mythology: More than Fairy Tales

Why did ancient cultures create myths? Mythology is more than fanciful stories. It’s a communication tool, using metaphors and symbols to explain the unexplainable.

When something seems impossible, people attribute it to gods or supernatural forces. For example, a fearless warrior might be described as blessed by the god of war. This wasn’t mere fantasy. These stories carried virtues, vices, and social values encoded in tales everyone could understand.

Myths weave together culture and belief, telling us not just what happened, but what people thought about events and characters. They provide clues about societies’ laws, religion, and values—all essential to interpreting their world.

Practical Monday Methods for Exploring the Past

Feeling ready to dive into this “foreign country” called history? Here are some practical tips to start your journey:

- Tune Your Senses: Listen carefully to the descriptions of places and times in historical sources. What did people see, hear, and feel? Imagine their environment and its sensory details rather than imposing modern noise and visuals.

- Look Up, Literally: When reading about medieval cities or ancient towns, think about their architecture. What buildings stood tallest? What materials were common? Remember, stone wasn’t just building; it was power.

- Challenge Whose Story You’re Hearing: Who wrote the record? Europeans? Indigenous peoples? Consider possible biases and missing voices. Seek alternative accounts, like oral histories or local narratives, to balance perspectives.

- Hold Back Modern Judgments: Instead of instantly criticizing historical figures for beliefs now considered wrong, try to understand their context. What did they know? What cultural or political forces shaped them?

- Use Mythology Wisely: Recognize myths as windows into values and beliefs rather than literal truth. This aids understanding cultures on their own terms.

A Personal Voyage: Why This Perspective Matters

Embracing the idea that the past is a foreign country changes how we connect with history. Instead of feeling alienated or overwhelmed by old customs and events, it turns into a vibrant adventure. You become a traveler with curiosity and respect.

For instance, understanding indigenous agency in African history reshapes Western-centric narratives. It highlights how African political landscapes evolved independently. This shift corrects distorted “colonial” stories that once dominated textbooks.

Similarly, acknowledging the sensory world of medieval peasants helps us appreciate their lived realities. It’s not just dusty old facts—it’s life, rich and vivid in its own right.

Wrapping It Up

Monday Methods asks us to reset how we approach history. Forget that history is just dusty dates and distant rulers. Instead, understand that the past operates by its own rules. Smell the air of that medieval village. Feel the authority radiating from a stone cathedral miles away. Hear the different echoes in African political struggles untouched by European drama.

The past is indeed a foreign country—strange, profound, and full of lessons—if only we learn its language.

So next Monday, when you pick up a history book or watch a documentary, ask yourself: Am I a tourist with a guide or just someone looking for familiar landmarks? Approaching history with humility brings a richer, more truthful experience. And who knows? You might even enjoy the trip.

What sounds might a medieval villager hear compared to today?

A medieval villager hears mainly work noises, animals, and natural sounds like the wind. Loud or heavy sounds, like armored riders, signal important visitors early, unlike today’s constant surrounding noise.

How did architecture signal power in medieval cities?

Large stone cathedrals or castles stood out sharply among smaller buildings. Seeing a massive cathedral from miles away showed who held authority in the city before modern architecture existed.

Why is it important to reconsider colonial narratives in African history?

Colonial records often reflect the colonizers’ viewpoint. African political events sometimes occurred independently of European influence, revealing a fuller, less Eurocentric history.

How should we view Lovecraft’s political views in their historical context?

Lovecraft’s partial support for Hitler must be understood in his era’s context and his anti-Bolshevik stance. These views were debated then but do not align with today’s moral standards.

What role did mythology play in ancient societies?

Myths used metaphor and symbolism to explain impossible or awe-inspiring events. Gods and heroes symbolized traits and virtues important for communication and understanding in early cultures.