The British treated Hong Kong as a colony much better than India or Ireland primarily because of strategic, geopolitical, and pragmatic reasons rather than benevolence. Post-World War II constraints, proximity to Communist China, and the need to maintain local support shaped a unique approach towards Hong Kong’s governance, which differed markedly from the treatment of India or Ireland.

Hong Kong’s situation after WWII was unlike most British colonies. The British faced a weakened empire amid Cold War tensions. Crucially, they governed a tiny territory directly adjacent to Communist China, whose People’s Liberation Army could take Hong Kong rapidly if it chose. This made Hong Kong geopolitically vulnerable and practically indefensible without local cooperation.

To retain control, Britain recognized it needed two essential factors: first, the support of Hong Kong’s local population; second, to develop a strong, distinct Hong Kong identity separate from mainland China. Unlike in India or Ireland, where nationalist movements aimed for independence, Hong Kong’s identity was nurtured to bolster allegiance to colonial rule.

- Postwar colonial governments organized events like the Hong Kong Festival and Clean Up Hong Kong campaign to promote communal pride.

- They advanced social welfare through major initiatives, notably the Ten-year Housing Plan initiated during Governor Murray Maclehose’s term, which dramatically improved housing and hygiene standards.

- Efforts also included stamping out corruption using bodies like the Independent Commission Against Corruption.

This social stability and distinct identity fostered popular support for the colonial government. Such support was tactical. The British acted not out of much kindness but to create local buy-in essential for retaining their hold next to a hostile Communist regime.

The 1967 leftist riots, inspired by the Chinese Communist Party, underscored this necessity. The violent uprising challenged colonial rule, and although Hong Kong suppressed it, the nearby Portuguese colony of Macau faced defeat in similar 1966 unrest. There, the governor had to make humiliating concessions, effectively ceding sovereignty to China. The British feared such a fate and thus sought to avoid alienating Hong Kong’s population.

Historical events heavily influenced British policies. The Communist Revolution in China shaped Cold War geopolitics. Sino-British power dynamics made Hong Kong a vital bargaining chip. The British had to maintain Hong Kong’s stability to preserve their international standing during tense negotiations before the 1997 handover.

Postwar reforms reflected this pragmatism. Governor Mark Young resumed power in 1946 and proposed increasing Chinese participation in colonial governance to generate goodwill. However, this faced opposition from some officials and business interests fearing loss of control. Meanwhile, Beijing, particularly Premier Zhou Enlai, warned Britain against making Hong Kong a self-governing dominion like Singapore. These interactions complicated British attempts to balance reform and control.

Hong Kong’s booming economy also played a part in better treatment. The colony adopted a non-interference policy fostering a free market on China’s doorstep. By the late 20th century, Hong Kong’s economy was worth nearly 20% of all China’s GDP. This economic dynamism offered Britain significant advantages and incentives to maintain a stable, well-governed colony.

In contrast, British rule in India and Ireland involved large populations with strong nationalist and independence movements. Both were geographically vast and difficult to govern directly through local elites without conflict. British policies in India often prioritized extractive economic goals over social welfare. Meanwhile, Ireland’s political and religious conflicts fueled deep resistance to colonial rule.

The British government managed Hong Kong differently because of its size, lack of nationalist independence aspirations compared to India and Ireland, and the critical geopolitical context of the Cold War. This unique cocktail of factors compelled Britain to provide a measure of social welfare, foster local identity, and maintain political accommodation to secure its fragile grip.

| Aspect | Hong Kong | India and Ireland |

|---|---|---|

| Geopolitical Context | Bordered Communist China; Cold War tensions | Colonies with internal nationalist independence movements |

| Local Identity | Fostered a distinct “Hongkonger” identity | Nationalist identities opposed British rule |

| British Strategy | Build local support to maintain control | Suppress nationalist movements; more direct control |

| Economic Policy | Free market boost; economic growth encouraged | Extractive economy; resources mainly benefitted Britain |

| Social Welfare | Major social programs; housing and anti-corruption efforts | Limited welfare; focus on control and resource extraction |

Britain’s relatively better treatment of Hong Kong emerges as a calculated survival strategy. The colony’s small size and proximity to Communist China meant that fostering local loyalty was the only effective way to maintain power. This contrasted deeply with the British approach in larger, more rebellious colonies like India and Ireland, where authoritarian policies, economic exploitation, and political suppression were common.

- Hong Kong’s colonial governance was shaped by post-WWII constraints and Cold War pressures.

- Local identity and social welfare programs were developed to secure popular support.

- The 1967 leftist riots highlighted the threat from Communist China, reinforcing British caution.

- Economic growth and non-interference policies differentiated Hong Kong’s experience.

- Geopolitical realities—proximity to China and Cold War dynamics—drove Britain’s pragmatic approach.

Why Did the British Treat Hong Kong as a Colony Much Better Than They Treated India or Ireland?

Simply put, the British treated Hong Kong better because they needed to keep it—no funny business—near a fierce Communist giant and avoid its fate as an easy ground lost to China. Unlike India or Ireland, Hong Kong’s geopolitical position forced Britain to pursue a pragmatic, people-friendly approach, rather than sheer domination or exploitation.

Sounds a bit like babysitting a cranky kid next to a sleeping dragon—handle with care, or face chaos.

An Empire Under Pressure: Post-WWII Hong Kong

Right after WWII, British colonial rule in Hong Kong was far from comfortable. The empire was crumbling globally. Hong Kong was basically indefensible, hunted from all sides by a growing Communist China. As one historian puts it, if the People’s Liberation Army (PLA) wanted Hong Kong, they could take it in a few days without breaking much sweat.

So what’s a colonizer to do when your prized possession is practically sitting on the edge of a lion’s den?

Build local goodwill. Britain realized it needed two things to cling to power: strong support from locals and to make Hong Kong *look and feel* totally different from mainland China. Distinctiveness was a survival tactic. You don’t just hold a colony by force; you win hearts.

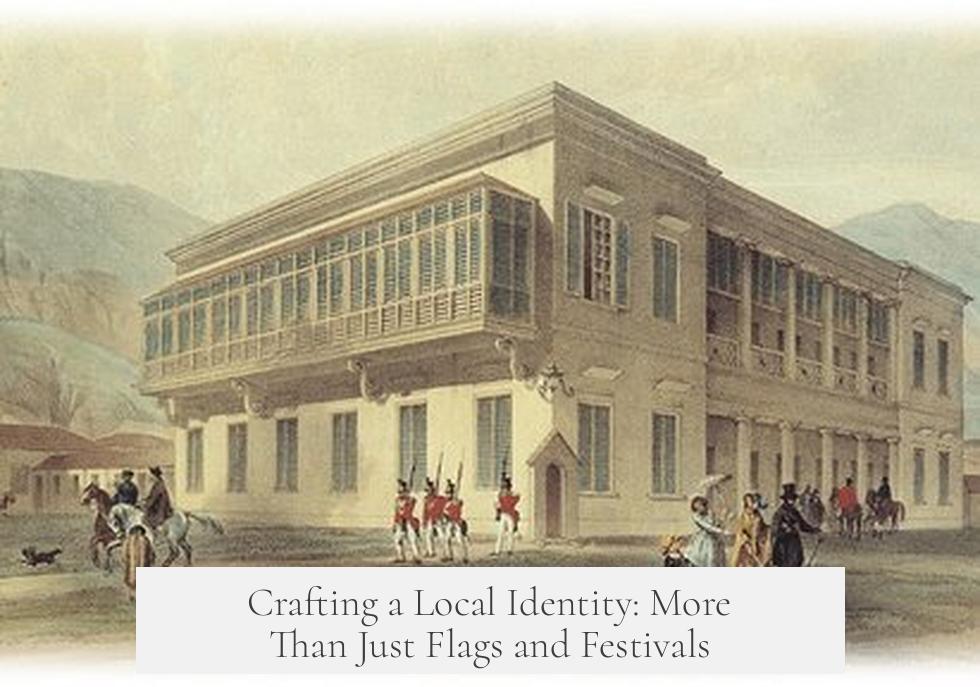

Crafting a Local Identity: More Than Just Flags and Festivals

Unlike the heavy-handed British rule in India or Ireland that bred resentment and rebellion, Hong Kong saw efforts to foster a sense of local pride. The government, post-WWII, launched events like the Hong Kong Festival and the Clean Up Hong Kong campaign. These initiatives weren’t just feel-good publicity—they helped build a communal identity separate from China’s shadow.

Remarkably, this worked. Today, many Hongkongers under 60 identify as Hongkongers *first*, not Chinese. Now, that’s quite the achievement in colonial management.

Alongside identity-building, social welfare programs blossomed. Under Governor Murray Maclehose, the Ten-year Housing Plan brought massive improvements. Public facilities, hygiene, and anti-corruption drives (hello, Independent Commission Against Corruption!) raised living standards.

Contrast this with India and Ireland, where exploitation and neglect often marked British rule. Making Hong Kong a *better place* was a strategic move to keep locals on the British side.

The 1967 Riots: A Wake-up Call and a Warning

When pro-Communist riots erupted in Hong Kong in 1967, backed by CCP agitators, the British authorities cracked down—but they also took a hard lesson. Nearby Macau, under Portuguese rule, had suffered a similar uprising in 1966 which ended disastrously for the colonizers. The Macanese governor had to publicly apologize under Mao’s portrait, effectively handing sovereignty to China.

The British were determined not to repeat that mistake in Hong Kong. It was a clear signal: without local support, colonial rule was doomed.

Political Reforms: Walking the Tightrope

Governor Mark Young’s post-war push for reform was ahead of its time. He wanted to increase Chinese representation in government and replace European officials with local Chinese officials. But surprise, surprise—the notion wasn’t warmly welcomed. Business leaders, Foreign Office officials, and some colonial staff saw it as a threat to authority.

Meanwhile, there’s an intriguing twist: Chinese Premier Zhou Enlai allegedly warned the British against turning Hong Kong into a self-governing dominion like Singapore. Declassified memos hint the British might have genuinely feared provoking Beijing’s wrath.

This delicate dance of politics kept Hong Kong’s regime cautious but more inclusive compared to India’s rigidly exploitative system or Ireland’s harsh military rule.

Cold War Chessboard and Geopolitical Realities

During the Cold War, Hong Kong became a significant piece on the chessboard between East and West. Sino-British negotiations and events like the 1989 Tiananmen Square massacre shook British confidence but didn’t push them to tighten the grip ruthlessly.

Why? Because any heavy-handedness risked pushing locals into China’s arms. Maintaining a cosmopolitan, thriving Hong Kong with decent living standards became the British play.

Economics: The Magic Wand

Hong Kong’s economic boom was no accident. Its free-market policies and legal framework positioned it as a lucrative entrepôt at China’s doorstep. By 1997, Hong Kong’s economy was worth 20% of all China’s GDP. That’s no small potatoes.

This starkly contrasts with the economic exploitation and famines experienced in India and Ireland under British rule.

The British strategy emphasized non-interference in business and fostering conditions for economic growth. In return, locals got jobs, rising incomes, and overall better life quality.

Lessons from History: Why Not Repeat the Old Mistakes?

Look at India and Ireland. The British approach involved extracting resources, suppressing local culture, and implementing policies that often starved people or fueled rebellion. The fallout was decades of conflict, resistance, and eventually, independence through sometimes violent means.

Hong Kong’s case is different

. The British knew if they ruled like old-school colonizers, Hong Kong would rival their lost colonies and slip fast. So, pragmatism over harsh measures.

So, What Can We Take Away?

- Geopolitical Pressure Shapes Colonial Policy. Hong Kong’s proximity to Communist China forced Britain to innovate colonial governance.

- Local Identity Matters. Creating a “Hongkonger” consciousness was a clever tool to resist reunification pressures.

- Economic Opportunity Spurs Cooperation. A booming economy gave locals a stake in the colonial system.

- Fear of Losing Control Leads to Welfare Improvements. Social programs and anti-corruption efforts were not acts of kindness but pragmatic investments to retain loyalty.

- Political Reforms, though limited, Differ from Earlier Colonies. Efforts to include local Chinese in governance contrast starkly with India and Ireland.

In short, the British treated Hong Kong better not because they suddenly became benevolent rulers but because they had no other choice. The stakes were entirely different from those in India or Ireland.

Would India or Ireland have appreciated such a strategy? Maybe. But the British Empire’s collapse left scars filled with misplaced arrogance and neglect there. In Hong Kong, the threat looming from just across the border rewrote the colonial playbook.

Next time someone asks why the British seemed nicer in Hong Kong, remember: when you’re holding a colony next to a looming dragon, it’s wiser to be a smart neighbor than a brutal landlord.

“The British were trying to create popular support for colonial rule — not because they were benevolent, but because it was their only way to hold onto power near a hostile Communist power.”

Now, isn’t that a history lesson packed with irony? Treat people decently—because you *can’t* afford not to. A bit of pragmatic kindness that ironically created one of the world’s most dynamic cities by the end of the 20th century.

Why did the British focus on building a distinct Hong Kong identity post-WWII?

Hong Kong was next to Communist China and indefensible. Britain needed local support to keep control. Creating a unique Hong Kong identity helped separate it from China and build loyalty among residents.

How did economic policies shape the British approach to governing Hong Kong?

The British adopted a non-interference policy that boosted Hong Kong’s economy. By 1997, its economy was 20% the size of mainland China’s. Economic success helped gain local support and justified colonial rule.

What lessons did Britain learn from the 1967 riots in Hong Kong?

The 1967 CCP-backed riots showed the threat of Communist influence. After Macau’s defeat in 1966, Britain realized it must secure local backing and crack down on unrest to avoid losing Hong Kong.

Why was British rule in Hong Kong more reform-oriented after WWII compared to India or Ireland?

Hong Kong was geopolitically sensitive, surrounded by Communist forces. To maintain control, Britain introduced reforms giving more local representation and improved welfare, unlike the harsher approach in India and Ireland.

Did geopolitical factors influence British policies toward Hong Kong differently than other colonies?

Yes. The Cold War, Communist China’s rise, and Sino-British negotiations created unique pressures. Britain saw Hong Kong as a strategic outpost requiring careful management, unlike colonies more distant from global power struggles.