The ATF and DEA exist as separate agencies from the FBI due to their distinct historical origins, specialized missions, and the need to maintain a balance of power within the federal law enforcement system.

The ATF, originally established in 1886 within the Treasury Department’s Bureau of Internal Revenue, evolved through various governmental reorganizations. During Prohibition, it served as the federal agency overseeing alcohol control and later became part of the FBI in 1933. However, after Prohibition ended and with the passage of the Volstead Act, it transferred to the Justice Department as the Alcohol Tax Unit. Its role expanded significantly when the Gun Control Act of 1968 designated the ATF to enforce federal firearms laws. The Homeland Security Act of 2002 reaffirmed its position under the Justice Department, solidifying its role distinct from the FBI.

The DEA, on the other hand, was created in 1973 by President Nixon in response to escalating drug-related issues. Its establishment consolidated various federal drug enforcement efforts into a single agency focusing exclusively on combating drug trafficking and abuse. The DEA has consistently operated under the Justice Department’s jurisdiction but remains separate from the FBI, emphasizing its specialized drug enforcement mission.

Both agencies’ separation from the FBI reflects the need for specialized focus. The ATF’s responsibilities span alcohol, tobacco, firearms, and explosives regulation, while the DEA targets drug law enforcement. This division allows each agency to develop expertise and resources tailored to their unique challenges. Such specialization enhances enforcement effectiveness and judicial outcomes.

Additionally, the principle of checks and balances strongly influences their independence. Combining these agencies under the FBI could concentrate excessive investigative power within a single entity. By maintaining them as separate agencies, the federal system prevents undue power accumulation, promoting oversight and accountability across law enforcement bodies.

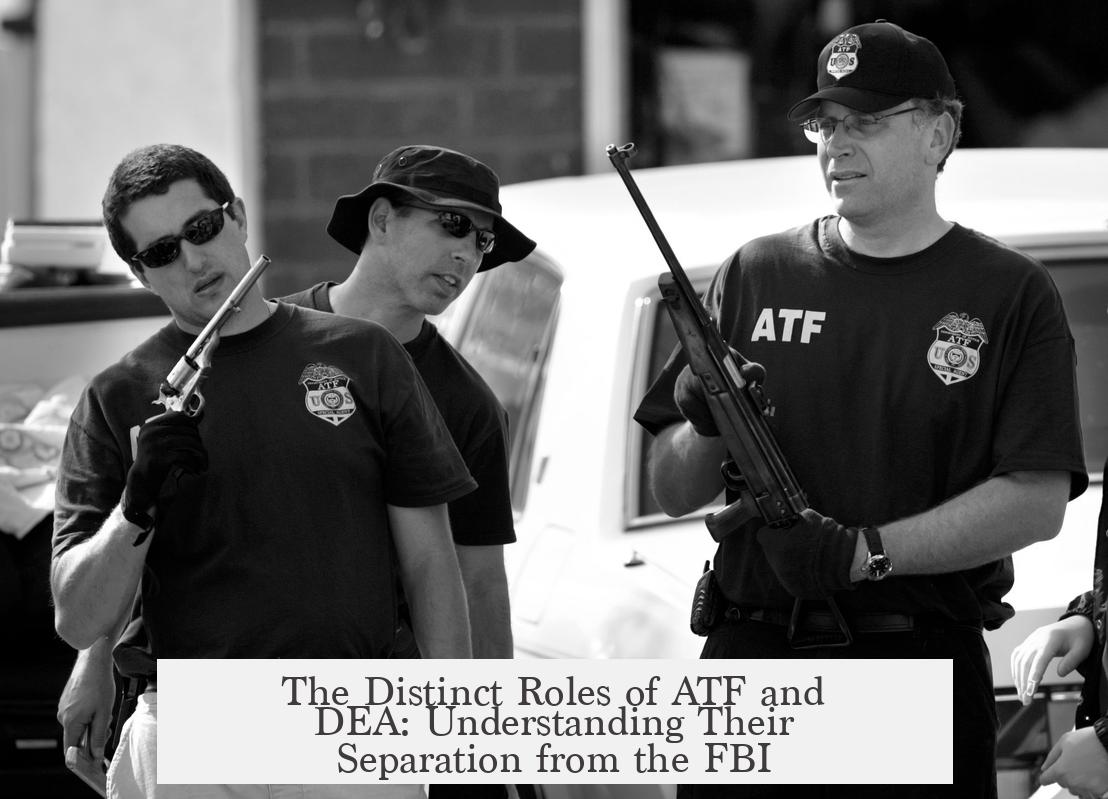

| Agency | Primary Role | Parent Department | Reason for Separation |

|---|---|---|---|

| ATF | Enforce laws on alcohol, tobacco, firearms, explosives | Justice Department | Specialized enforcement; historical evolution; checks and balances |

| DEA | Enforce federal drug laws | Justice Department | Specialized drug enforcement; organizational focus; checks and balances |

| FBI | Broad federal investigations, counterterrorism, intelligence | Justice Department | Broad investigative scope, no overlap with ATF/DEA specialization |

- The ATF’s roots trace back to the Treasury Department and Prohibition era regulations.

- The DEA was established in 1973 to unify federal drug enforcement efforts.

- Specialized missions require independent agencies for focused law enforcement.

- Separation supports the government’s system of checks and balances.

- Each agency operates under the Justice Department but maintains distinct responsibilities.

Why Does the ATF and DEA Exist as Separate Agencies From the FBI?

Simply put, the ATF and DEA operate as separate agencies from the FBI due to their highly specialized missions, historical developments, and the U.S. government’s principle of checks and balances, which prevents any one agency from becoming too powerful.

At first glance, it might seem easier to lump all federal law enforcement under one massive umbrella—the FBI, renowned for tackling everything from national security to violent crime. But the reality is more nuanced. The ATF and DEA trace unique paths and exact roles that justify their standalone status, ensuring that federal enforcement is sharper, focused, and balanced.

The Tangled Roots of the ATF

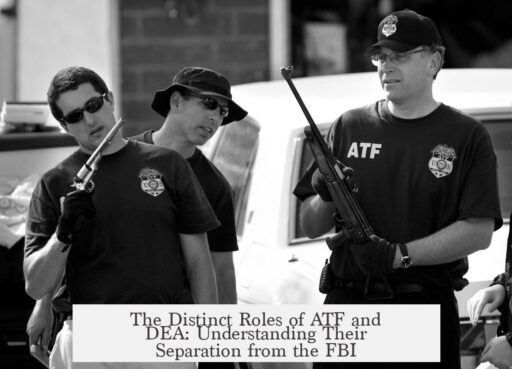

Let’s rewind to 1886, when an agency now known as the Bureau of Alcohol, Tobacco, Firearms and Explosives (ATF) first emerged—not as a law enforcement powerhouse, but as a tax collection unit within the Treasury Department’s Bureau of Internal Revenue. Its early life focused on alcohol taxes, which made sense because taxing booze was big business even before Prohibition struck in the 1920s.

During Prohibition, the ATF played a starring role in enforcing alcohol bans. But here’s a twist: in 1933, the ATF was shoehorned into the FBI, creating a period where gun and alcohol enforcement fell under J. Edgar Hoover’s sprawling FBI umbrella. However, when the Volstead Act repealed Prohibition, the ATF bounced back to the Justice Department and was renamed the Alcohol Tax Unit (ATU). This move made it clear that its primary job wasn’t every crime imaginable but something more focused: alcohol and later, firearms regulation.

In fact, the spotlight brightened on the agency’s firearms duties after the Gun Control Act of 1968 gave birth to the ATF’s current name. Suddenly, the agency wasn’t just about booze taxes. It became the prime enforcer of federal gun laws. The Homeland Security Act of 2002 shuffled the ATF again within the Justice Department, but by then, the agency had firmly established its specialized mission distinct from the FBI’s general criminal investigations.

The Birth and Rise of the DEA

Meanwhile, drugs became a growing national concern in the post-1960s era. Enter Richard Nixon and his 1973 “War on Drugs,” which birthed the DEA. This agency was designed from day one to be laser-focused on one thing: enforcing federal drug regulations. Unlike the ATF’s winding bureaucratic history, the DEA’s origins weren’t piecemeal or merged with other agencies. It was created under the Justice Department as a specialized drug law enforcer, consolidating functions that had previously been scattered across multiple agencies.

Drug trafficking, usage, and sale present complex, multi-jurisdictional challenges that require dedicated resources and expertise. The DEA’s standalone status allows it to focus smartly and aggressively on this mission without being bogged down by the broader investigations the FBI handles.

Why Not Just Put Them All Under the FBI?

Couldn’t the FBI just absorb the ATF and DEA and manage all federal crimes together? Sure, but that’s where specialization and checks and balances come into play. Combining these agencies under the FBI could dilute the expertise each has developed, making enforcement less effective overall.

Both the ATF and DEA focus on niches requiring technical knowledge and specialized enforcement practices. The ATF handles firearms identification, tracing, and enforcement law, while the DEA tackles drug cartels and narcotics trafficking. Mixing these operations under the FBI risks blurring focus and priorities.

There’s also a constitutional angle. The U.S. government functions on a principle ensuring no single body becomes too omnipotent. Giving the FBI control over all criminal investigations—guns, drugs, violent crime, terrorism—would centralize excessive power in one agency. This setup would flip the delicate balance the Founders envisioned.

Instead, maintaining these agencies independently safeguards against abuse, promotes a system of internal checks, and encourages cross-agency collaboration rather than monopolization. The FBI, DEA, and ATF often cooperate but maintain distinct mandates and jurisdictions.

Real World Benefits of Separate Agencies

- Expertise Built Over Time: The ATF’s long history in firearms regulation means it understands gun laws and tracing better than a general investigator ever could.

- Nimble Responses: DEA agents are trained to dismantle drug trafficking networks with specialized strategies that differ wildly from other criminal probes.

- Checks and Accountability: Separate oversight and administration limit bureaucracy from turning into unchecked authority.

Imagine if you were baking a cake but had to mix every ingredient at once with no distinct measuring spoons. You’d end up with a mess. Federal law enforcement works similarly: specific agencies keep order and precision in their tasks.

Quick Tips on Understanding Federal Law Enforcement Agencies

- Think of the FBI as the “jack of all trades” investigator, tackling broad crime categories and national security.

- The ATF specializes in alcohol, tobacco, firearms, and explosives—sometimes called the “go-to” for gun law enforcement.

- The DEA zeroes in on drug laws, working to stop narcotics trafficking and abuse nationwide.

Each agency is a vital cog in the law enforcement machine, tailored to ensure our justice system works efficiently and fairly.

So, Why Does This Matter to You?

Knowing these distinctions helps citizens appreciate how complicated federal law enforcement really is. It also clarifies which agency handles which issues—important if you’re ever involved in legal matters or just want to make sense of news headlines involving drugs, guns, or federal crimes.

Next time you see those acronyms—ATF, DEA, FBI—remember, they’re not just letters. They represent decades of history, clear missions, and a careful balance of power designed to keep America safe and fair.

Why is the ATF separate from the FBI despite its historical ties?

The ATF started in the Treasury Department and later moved around. Its focus on alcohol, tobacco, firearms, and explosives enforcement required specialized attention. Keeping it separate helps maintain clear roles and expertise.

What was the main reason for creating the DEA as its own agency?

The DEA was created to focus solely on drug enforcement. Consolidating drug law enforcement into one agency made efforts more coordinated and effective, distinct from the broader FBI responsibilities.

How does specialization affect the separation of ATF, DEA, and FBI?

Each agency targets specific crimes. The ATF handles firearms and explosives; the DEA focuses on drug crimes. This specialization improves the effectiveness of law enforcement practices.

Does separating these agencies relate to the US principle of checks and balances?

Yes. Separating agencies prevents any one from gaining too much power. Having the ATF and DEA outside the FBI helps balance federal investigative authorities.

Could combining the ATF and DEA with the FBI reduce effectiveness?

Combining them could blur their focused missions. Each agency pursues distinct goals, and combining could dilute their ability to address complex, specialized crimes.