Ladino (Judeo-Spanish) was not a commonly spoken language in North African Jewish communities that identified as Sephardic because the Judeo-Spanish dialect spoken there, known as Haketia, was regionally distinct and less widespread. These communities experienced different historical, political, and linguistic developments compared to the Ladino-speaking Sephardim of the Ottoman Empire. This resulted in less literary tradition, weaker intercommunity linguistic cohesion, and limited use of Ladino as a lingua franca.

North African Sephardic Jews primarily spoke a dialect called Haketia. This variant blended Spanish with local influences, especially from Moroccan Arabic (Darija) and Hebrew. Haketia remained in use until fairly recently but did not develop the same status or wide recognition as classical Ladino spoken in Ottoman lands.

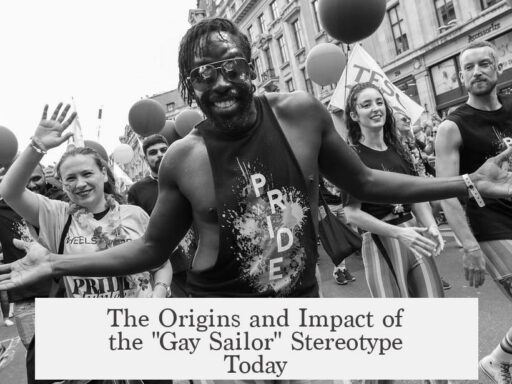

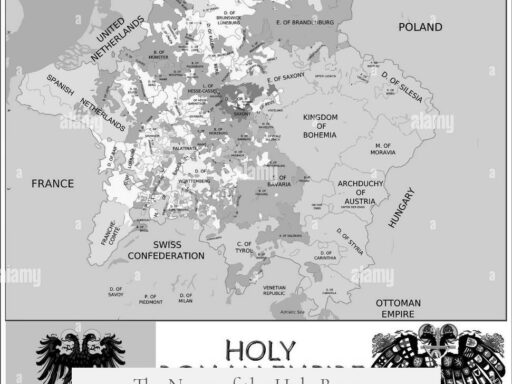

The divergence between these dialects relates to the distinct political and social contexts of the respective Jewish communities. Ladino speakers mostly resided within the Ottoman Empire’s territories—in cities across Greece, the Balkans, and Anatolia. Here, Jews enjoyed a relatively hands-off governance by the Ottomans, who generally allowed minority groups autonomy in internal affairs. This autonomy fostered cultural and linguistic preservation. Ottoman policy rarely pressured minorities to adopt Turkish, encouraging stable use of Ladino.

In contrast, North African Sephardic communities lived under different political regimes, mainly the French colonial presence in the 19th and 20th centuries. The influence of French, promoted by institutions like the Alliance Israélite Universelle, imposed new linguistic pressures. The communities were encouraged to learn French, which shifted linguistic dynamics away from local Judeo-Spanish variants. Mutual intelligibility existed locally between Moroccan and Algerian Jewish dialects, but no widespread, standardized written dialect functioned as a lingua franca across the Maghreb’s Sephardic Jews.

| Aspect | Ladino in Ottoman Sephardic Communities | Haketia in North African Sephardic Communities |

|---|---|---|

| Political Context | Ottoman Empire’s hands-off minority approach | French colonial influence and local political shifts |

| Language Pressure | Little pressure to abandon Ladino; Turkish not enforced | French introduced, pressured learning; local Arabic influences |

| Literary Tradition | Strong early written and printed tradition; literature and translations since 1500s | Limited written corpus and standardized literature |

| Lingua Franca | Ladino acted as shared lingua franca among dispersed communities | No shared written lingua franca; local dialects varied regionally |

| Community Interaction | Multilingual urban centers with Greek, Slavic, and Turkish populations | Mostly regional interactions with limited external linguistic influence |

The Ottoman environment facilitated Ladino’s survival and growth. Jews in Ottoman lands benefited from relative political autonomy and involved themselves in lucrative trade networks, maintaining linguistic and cultural stability. The robust literary output in Ladino, including translations and religious texts since the 1500s, strengthened the language as a tool of communication and identity.

North African Sephardic Jews retained strong ties to their Spanish heritage, including their identity and language roots. However, the local Judeo-Spanish dialects evolved differently due to geographical separation, lack of centralized written communication, and colonial language pressures. Moroccan Jews spoke hybrid forms combining Spanish and Arabic elements, differing from Judeo-Algerian and other North African variants.

Ladino’s limited presence among North African Sephardic Jews does not mean the absence of Judeo-Spanish influence. Instead, it reflects distinct trajectories shaped by political histories, social contexts, and regional language environments.

- Haketia, a regional Judeo-Spanish dialect, was common in North African Sephardic communities, not classical Ladino.

- The Ottoman Empire’s tolerant policy on minorities allowed Ladino to thrive in its territories.

- Ladino had a strong written tradition and served as a lingua franca across Ottoman Jewish communities.

- North African Sephardic dialects remained regionally diverse with limited standardized written use.

- French colonial influence and local Arabic dialects shaped language use in North African Jewish communities.

Why Was Ladino (Judeo-Spanish) Not a Commonly Spoken Language in North African Jewish Communities That Also Identified as Sephardic?

Here’s the straight scoop: Ladino, the Judeo-Spanish language famously spoken by Sephardic Jews, didn’t take firm root in North African Jewish communities because those communities developed their own local dialects like Haketia, experienced very different historical influences, and lacked the strong written and cultural infrastructure Ladino enjoyed under the Ottoman Empire.

Sounds simple enough, right? But the story is richer and worth unpacking.

The Maghreb Has Its Own Unique Judeo-Spanish Flavor: Haketia

In North Africa, especially Morocco and parts of the Maghreb, Jewish communities didn’t speak “classic” Ladino as understood on the eastern side of the Mediterranean. Instead, they spoke Haketia. This Judeo-Spanish dialect blended old Spanish with Arabic and Hebrew. While Haketia shares roots with Ladino, it remained far less famous and spoken by fewer people.

Haketia survived until comparatively recently, but its speakers never reached the wide dispersion or cultural prominence Ladino speakers had. The mere existence of this dialect highlights that North African Jews preserved their Sephardic identity but tailored their language to local linguistic and cultural realities.

Distinct Political and Historical Contexts Shape Language Use

One major reason Ladino thrived elsewhere is the environment of the Ottoman Empire. Ladino speakers lived in cities where Turkish was rarely the dominant tongue and minority cultures faced little pressure to assimilate linguistically. The Ottomans took a “hands-off” approach, allowing Jewish communities to manage their own affairs, especially in trade.

Because the Ottoman Empire fostered this cultural autonomy, Ladino could develop robust written traditions, trading networks, and communal ties. This meant Ladino wasn’t just a spoken language; it was a bridge for communication across countries and a medium for literature, religion, and commerce.

Conversely, North African Jews faced different sociopolitical pressures. When French colonizers arrived, language shifts came quickly and intensely, diminishing the space for local Judeo-Spanish dialects. French became the language of education and upward mobility, superseding Haketia and any spoken form of Ladino.

Ladino’s Strength: A Rich Literary and Printed Tradition

Unlike Haketia or regional Judeo-Spanish dialects, Ladino benefited from an early literary flowering. By the 1500s, figures like Moses Almosnino were translating religious and secular texts into Ladino, giving it a foothold in print culture. This didn’t just preserve the language; it amplified it.

With newspapers, books, and religious writings in Ladino, the language became a unifying force across diverse Sephardic communities scattered from Istanbul to the Balkans. It was a true lingua franca, knitting together multi-ethnic neighborhoods.

The Maghreb’s Fragmented Linguistic Landscape

North African Jewish communities were linguistically more fragmented. Moroccan Jews spoke a Darija-Spanish hybrid; Algerian Jews had their own Judeo-Arabic blends. There wasn’t a strong written lingua franca linking these dialects. Commerce and communication more often relied on local Arabic dialects, Hebrew, or French, not Haketia or any form of Ladino.

This limited the reach and endurance of a singular Judeo-Spanish language. While these communities did maintain their Spanish-infused identities, the absence of a unified literary tradition meant their dialects didn’t gain the cultural prestige or lasting power Ladino did.

Ottoman Empire’s Non-Interference Boosted Ladino’s Resilience

The Ottoman Empire’s laissez-faire posture was crucial. By letting Jews in their trading cities thrive culturally and linguistically, Ladino speakers kept their language vibrant. The empire recognized the economic benefits of tolerating distinct communities, even nurturing their languages.

This wasn’t the case in the Maghreb, where colonial powers imposed new languages and social structures fairly quickly. French replaced Arabic variants and Judeo-Spanish hybrids in schools and public life, undermining local dialects.

So, What’s the Takeaway?

North African Jewish communities, despite identifying as Sephardic, didn’t widely speak Ladino because they developed their own distinct Judeo-Spanish dialect, Haketia, shaped by local language contact, politics, and trade relationships. Unlike Ladino speakers in the Ottoman domains, these communities lacked:

- A unified written standard or literary tradition.

- A socio-political environment that encouraged language preservation.

- Intercommunity networks to sustain one lingua franca.

Instead, they lived in linguistic mosaics, balancing Spanish influences with Arabic dialects, Hebrew, and later French. This mosaic shaped their languages and identities in ways that diverged significantly from the familiar Ladino story of the Balkans and eastern Mediterranean.

Curious About Lingering Traces?

Today, you can still hear echoes of Haketia in some Moroccan and North African Jewish diasporic communities, particularly in Israel. But it’s increasingly rare, overshadowed by Hebrew, French, and modern Spanish. Its survival depends on cultural revival efforts and the recounting of this rich but lesser-known chapter of Sephardic history.

Isn’t it fascinating to see how geography and politics play a huge role in shaping what language a community speaks? Languages aren’t just about words—they’re about history, power, and identity all woven together.

For anyone looking to explore Sephardic culture, remember: Ladino isn’t the entire story. Exploring Haketia and other Judeo-Spanish dialects opens doors to the vibrant diversity within Sephardic traditions.