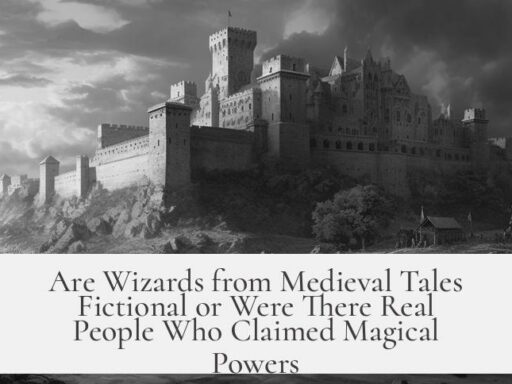

Severed heads on pikes and sticks were indeed used historically and across many cultures as a means of displaying power, deterring enemies, signaling prestige, or exacting punishment. This practice was widespread, appearing from ancient Rome to indigenous North American tribes, and persisted into early modern Europe and colonial America. The contexts and methods varied, but all involved public display in prominent sites to communicate messages of authority or spiritual significance.

In the Late Roman Republic and early Imperial periods, figures such as Gaius Marius and Lucius Cornelius Cinna introduced the gruesome display of severed heads during political purges. These heads were mounted on the Rostra, the public speaking platform in Rome’s Forum. The practice served as a brutal warning to enemies and as a demonstration of control after violent takeovers.

Lucius Cornelius Sulla adopted the measure during his proscriptions, an organized campaign of political executions and confiscations. After him, the Second Triumvirate—Mark Antony, Marcus Aemilius Lepidus, and Gaius Octavian—revived the tradition. They publicly displayed heads on the Rostra to mark the victims of their purge. One notable example was the statesman Cicero. His head and hand were exhibited because of his vocal opposition to Mark Antony, symbolizing punishment for political dissent.

Among indigenous peoples of the Northwest Coast of North America, such as the Nu-cha-nulth (Nootka), Haida, and Tsimshian, heads and skulls held spiritual and social importance. These groups modified heads through cranial deformation and adornment with jewelry while individuals were alive, underscoring the head’s role as a vessel of identity and status.

In warfare, defeated enemies’ heads were taken and displayed as trophies to assert dominance and ensure spiritual control. The skull was often seen as the seat of the soul. Practitioners preserved chiefs’ skulls in special containers, sometimes even sleeping upon them to absorb power. Such displays were part of long-standing prestige maintenance, dating back more than three millennia.

In Britain, the practice of displaying severed heads continued into the 18th century, particularly in London. London Bridge was a notorious site for exposing the heads of executed criminals. Such displays served as deterrents to crime and rebellion, making authority visible and feared by the public.

In 17th-century Bohemia, after the Habsburg suppression of a noble revolt, 12 prisoners’ heads were placed in iron cages and hung from the Old Town Bridge Tower in Prague. This occurred after the Battle of White Mountain in 1620. The heads remained displayed prominently for years as a grim warning to others. This brutal message helped secure long-lasting submission to Habsburg rule for centuries.

In colonial New England, during King Philip’s War of the late 17th century, a similar practice appears. Metacom (known as King Philip), leader of the Native American resistance, was killed and dismembered by Anglo colonists. His head was set on a pike above Fort Plymouth’s gates, where it was left on public view for about twenty years. This served as both a practical and symbolic act of dominance over Native resistance.

| Culture / Period | Purpose of Display | Method & Location | Notable Example |

|---|---|---|---|

| Late Roman Republic & Empire | Political purge and deterrence | Heads mounted on Rostra platform in Rome | Cicero’s head and hand |

| Northwest Coast Native Tribes | Prestige, spiritual power, and war trophies | Heads/skulls adorned, displayed in ritual buildings and poles | Nu-cha-nulth, Haida, Tsimshian traditions |

| Britain (16th–18th century) | Crime deterrence and authority demonstration | Heads placed on London Bridge | Executed criminals |

| Bohemia (17th century, Habsburg Empire) | Political deterrence after rebellion | Heads in iron cages on Old Town Bridge Tower, Prague | Revolt leaders after Battle of White Mountain |

| Colonial New England (Late 17th century) | Suppress Native resistance | Head on pike at Fort Plymouth gate | Metacom (King Philip) |

The use of severed heads on public display served multiple overlapping functions:

- Power Assertion: Governments, victors, or dominant groups used this to project strength and control.

- Deterrence: Public horror induced by the display warned potential challengers or criminals.

- Prestige and Spiritual Symbolism: Especially in indigenous cultures, heads carried meanings about the soul, status, and power acquisition.

- Judicial Punishment: Display served as an extension of execution—marking the fate of condemned individuals and enforcing social order.

While the exact contexts and symbolism could differ, the practice’s persistence across time and geography highlights its effectiveness in communication by fear and respect in human societies.

- Severed heads on sticks were widely used across ancient to early modern societies.

- Rome’s political leaders used this during violent purges on the Forum’s rostra.

- Northwest Coast Native Americans displayed heads as war trophies and spiritual objects.

- British authorities displayed criminals’ heads on London Bridge into the 1700s.

- Bohemian Habsburg rulers exhibited revolt leaders’ heads for decades as deterrence.

- Colonial New England used head displays during King Philip’s War to quash rebellion.

- Methods included mounting heads on poles, poles with spikes, iron cages, often in prominent public locations.

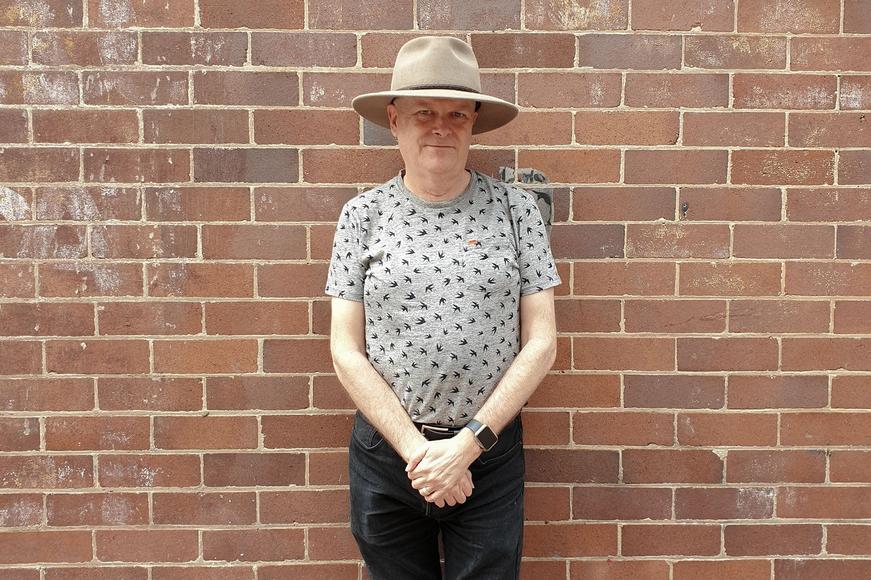

Were severed heads on pikes and sticks actually used? A deep dive into history’s chilling displays

Yes, severed heads on pikes and sticks were undeniably used throughout history. This grisly practice served many purposes—from terrifying enemies and asserting political dominance to displaying prestige and even spiritual beliefs.

How wide was this practice? It stretched across continents, centuries, and civilizations. From the late Roman Republic to Native North American tribes, from the streets of London to the bridges of Bohemia, the bare, bloody truth is that impaled heads were a very real part of human culture.

But what drives societies to take this gruesome route? And which cultures made a habit of it? Buckle up; here is a detailed journey through this macabre tradition.

The Roman Republic’s brutal political theater

Let’s start with ancient Rome—a city known for gladiators, emperors, and wild political power plays.

During the Late Roman Republic, generals like Gaius Marius and Lucius Cornelius Cinna ignited bloody purges after successful marches on Rome. Their signature move? Displaying severed heads on the Rostra, the public speaker’s platform.

This gruesome exhibit was more than an act of brutality. It was a savage warning to enemies and a chilling political statement. Lucius Cornelius Sulla, known for his ruthless purges called proscriptions, adopted this practice and expanded it.

Then came the Second Triumvirate—Mark Antony, Marcus Aemilius Lepidus, and young Octavian (later Augustus). They revived this tradition after forming their alliance. The most famous victim was the orator Cicero, whose head and hand were displayed for his vocal opposition.

Romans used severed heads on pikes not just to punish but to terrify and control. A public spectacle of power where dissent meant death and humiliation.

Northwest Coast Native Americans: heads as markers of status and soul connection

It might sound surprising, but severed heads also carried deep spiritual and social weight among certain Native American societies on the Northwest Coast.

Groups like the Kwakwaka’wakw, Nu-cha-nulth (Nootka), Haida, and Tsimshian used skulls and heads as powerful prestige symbols. Heads were often taken from enemies as war trophies and displayed prominently on poles.

But here’s the twist: the skull was sometimes considered the home of the soul. Owning and displaying an enemy’s skull wasn’t just about victory; it was about claiming spiritual power and status.

“[We] saw two human heads impaled upon the points of two poles… part of the skin and chin hanging down but the rest of the face, teeth & long black hair intact…” — Eyewitness account, Newcombe, 1928.

These ancient traditions extended back nearly 4000 years. Chiefs kept skulls in special buildings or even slept on beds of skulls, seeking strength and prestige from them.

Britain’s long tradition: London Bridge’s grim gallery

Jumping forward to 18th century Britain, severed heads on spikes lingered on London Bridge as a form of public intimidation.

The heads of criminals, traitors, and political enemies were displayed prominently. This gruesome showcase served as a warning about the fate awaiting lawbreakers and those who challenged royal authority.

Think of it as an early, morbid form of “wanted” advertising—only far less subtle.

The Habsburgs’ ironfisted warnings in Bohemia

The 17th century offers a dramatic example during the Thirty Years’ War, after the Bohemian nobility rebelled against the Habsburg Empire.

Following their defeat at the Battle of White Mountain, 27 rebel leaders faced execution in Prague’s Old Town Square. Twelve of their heads were encased in metal cages and hung from the Charles Bridge’s famed towers.

This was no mere act of cruelty. The heads dangled for nearly a decade, visible to anyone crossing this vital trade artery. The message was clear: defy the Habsburgs, and death with public disgrace awaits.

Remarkably, Bohemia never again rebelled for 300 years. Sometimes, harsh lessons do stick.

New England colonists and the aftermath of King Philip’s War

In colonial America, after King Philip (Metacom) died in battle in the late 1600s, his body was dismembered.

His head went to the gates of Fort Plymouth, mounted on a pike, staying there for twenty years as a stark message to the Native Americans and colonists alike.

The man who shot Metacom kept his hands—gruesome souvenirs reflecting the era’s brutal conflict dynamics.

Why did societies globally adopt this practice?

Public humiliation and deterrence are the obvious answers. Displaying severed heads was a visceral way to enforce power, quash dissent, or celebrate military victories.

But there were other layers. For some Native groups, skulls were more than trophies; they connected the living to the spiritual realm, conferring authority and prestige.

In political spheres like Rome or Bohemia, this practice was part of calculated state terror and control. It combined justice with spectacle.

So, how widespread was it, really?

The use of severed heads on sticks or pikes appeared on several continents: Europe, North America, and even among indigenous cultures of the Pacific Northwest.

Though the methods and meanings differed, the core function remained—communicating power through fear, status, or spiritual ownership.

What lessons emerge from this morbid tradition?

- Power displays can take many forms. Sometimes the message is subtle; other times, it’s brutally literal—like displaying a severed head.

- Culture shapes the meaning. A skull can be a warning sign, a trophy, or a sacred relic depending on the society.

- Humans have long harnessed imagery of death and dismemberment to assert control. It’s a stark reminder that symbols matter as much as actions.

Practical takeaway: When it comes to displays of power, less bloody is usually more effective—and more humane.

Today’s societies thankfully rely on law, rhetoric, and institutions—not severed heads—to maintain order. But knowing the past helps us appreciate peaceful progress.

Would today’s leaders dare use such gruesome displays? Probably not. But the echoes of those bloody pikes remind us how raw and visceral human politics can be.

References and further reading

- Chacon and Dye, 2007. The Taking and Displaying of Human Body Parts as Trophies by Amerindians. Springer.

- Toulky Českou Minulostí Volume 4, Petr Hora-Hořejš, Baronet, 1995.

- Královská Cesta, Jiří Všetečka, Panorama, 1998.

In summary, severed heads on pikes have served as a vivid, if gruesome, medium for communicating power—from Roman political purges to Native American spiritual traditions, from Old World justice to colonial warfare propaganda.

It’s one of history’s darker chapters, but it reveals a lot about human nature, culture, and the lengths societies have gone to enforce authority.

Were severed heads on pikes a common practice in ancient Rome?

Yes, during the Late Roman Republic, leaders like Gaius Marius, Sulla, and the Second Triumvirate used severed heads on the Rostra as political tools. Victims of purges, including Cicero, had their heads displayed to signal power and warn enemies.

Which Native American cultures displayed severed heads and why?

Tribes such as the Nu-cha-nulth, Haida, and Tsimshian on the Northwest Coast displayed human heads as war trophies. The skulls symbolized ownership, prestige, and spiritual power, often linked to beliefs about the soul residing in the head.

How long did Britain maintain the practice of displaying heads on pikes?

Heads were displayed on structures like London Bridge well into the 18th century. The practice served to deter crime and demonstrate authority, typically using heads of prominent criminals to send a public message.

What role did severed heads play after the Bohemian revolt in the 17th century?

After the revolt at the Battle of White Mountain, the Habsburgs displayed 12 rebel leaders’ heads in cages on Charles Bridge. This served as a warning to the population, helping maintain Habsburg control over Bohemia for centuries.

Did colonial Americans use severed heads for public display?

Yes, during King Philip’s War, Metacom’s head was placed on a pike over Plymouth’s fort gates for about 20 years. This act aimed to intimidate and demonstrate colonial dominance over Native peoples.