Edo-era Japan was not entirely isolated despite strict maritime restrictions implemented from 1633. These laws prohibited Japanese from traveling abroad under penalty of death to prevent piracy, control population movement, and block foreign influences like Christianity. However, Japan maintained selective international contact that allowed it to stay informed and engaged with the world.

Japan upheld formal diplomatic relations with neighboring countries including Korea, the Ryukyu Kingdom (modern Okinawa), and the Ainu of Hokkaido. Nagasaki served as a unique gateway where the Dutch East India Company operated and Chinese traders maintained informal contacts, although there were no direct ties with Ming China.

The Dutch presence was crucial for channeling information from Europe to Japan. Officials received annual reports known as Oranda Fusetsugaki (Dutch News Letters). These newsletters initially focused on threats from Catholic Iberian powers like Spain and Portugal but eventually expanded coverage to broader European affairs such as Russian expansion in Siberia and the Great Northern War (1700-1721). This steady flow of intelligence helped Japan understand shifting geopolitical dynamics without direct participation.

By 1720, the Japanese government officially sanctioned Rangaku or Dutch Studies. This intellectual movement enabled scholars to learn Western sciences, literature, and technology while excluding Christianity. Figures like Katsuragawa Hoshu and Honda Toshiaki advanced these studies and influenced Japan’s understanding of Western knowledge. Although some scholars faced persecution for dissenting views, the studies continued and flourished.

This selective openness meant Japan, though restricted, was not cut off. When Commodore Perry arrived in 1853 demanding Japan open its ports, the country was somewhat prepared. The knowledge gained via the Dutch and Rangaku scholars laid a foundation for Japan’s swift modernization during the Meiji Restoration, accelerating its rise as a global power.

| Aspect | Details |

|---|---|

| Maritime Restrictions | Travel abroad banned to prevent piracy and foreign influence |

| Formal Relations | Korea, Ryukyu, Ainu, Dutch in Nagasaki |

| Information Flow | Dutch News Letters reporting European politics and science |

| Rangaku | Study of Western science and culture, excluding Christianity |

| Preparation for Perry | Existing knowledge enabled rapid adaptation and modernization |

- Maritime bans limited travel but did not block foreign contact.

- Japan maintained diplomatic and trade ties through specific channels.

- Dutch intermediaries provided critical updates on global affairs.

- Rangaku promoted Western learning despite official restrictions.

- Japan’s preparedness by 1853 influenced its rapid modernization path.

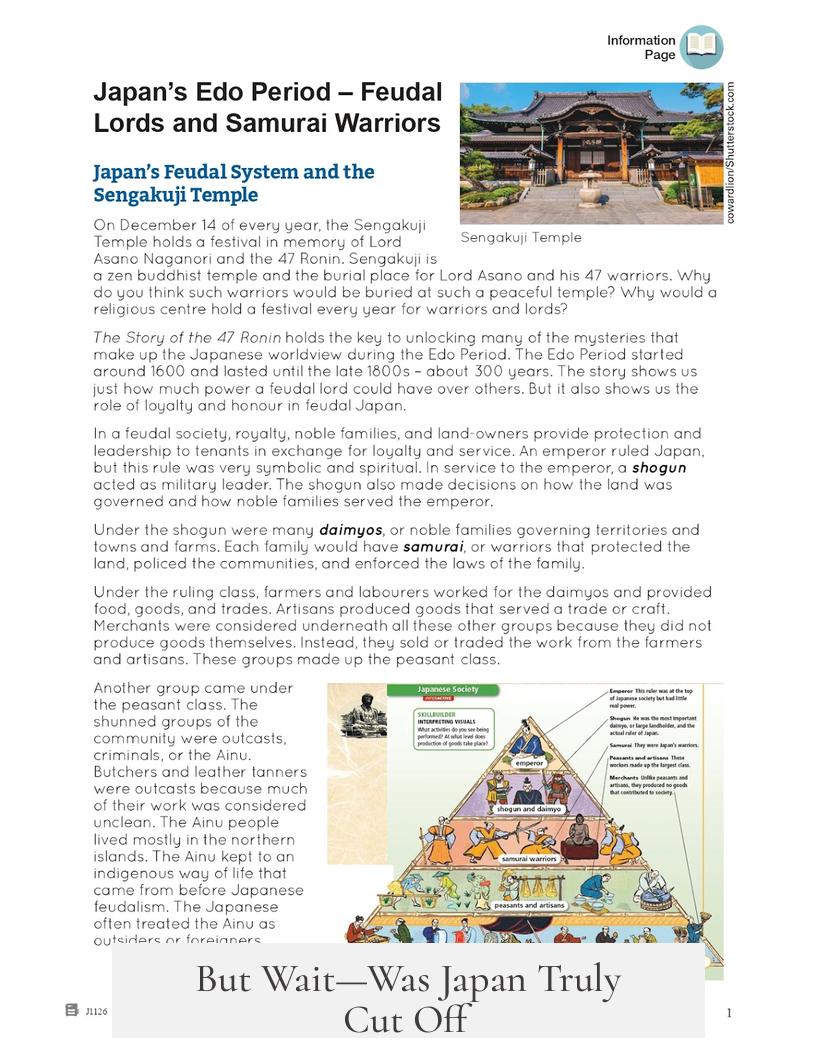

How Isolated Was Edo-era Japan Really?

Despite popular belief, Edo-era Japan (1603-1868) was not as isolated as many imagine. While the Tokugawa Shogunate imposed strict maritime restrictions designed to control movement and ideas, the country remained actively engaged with the world in surprising ways. The story of Japan’s isolation is more complex than a simple shuttering of doors and gates.

So, how isolated was Edo-era Japan? Far from a locked fortress, the period known as sakoku (“closed country”) was really a state of selective interaction. Let’s unpack that nuanced reality step by step.

Maritime Restrictions That Shaped Edo Japan

Starting in 1633, Japan enforced strict maritime restrictions prohibiting Japanese people from traveling abroad. This wasn’t just a whim—it was a hard rule backed by the harshest penalties, including death, for violators. Why so extreme? The Shogunate aimed to prevent:

- Population destabilization through mass emigration

- Maritime piracy

- The import of foreign ideas considered dangerous, like Christianity

- Japanese subjects becoming mercenaries or stirring conflicts overseas

Effectively, the government wanted to keep its people and its culture safe from outside turmoil. This created a sort of controlled quarantine on movement while tightening internal governance.

But Wait—Was Japan Truly Cut Off?

Not exactly. Japan never severed external diplomatic ties completely. It maintained official relations with Korea, the Ryukyu Kingdom (present-day Okinawa), and the Ainu peoples of Hokkaido. Japan also engaged actively with foreign traders and diplomats, notably the Dutch East India Company, stationed in Nagasaki.

Informal connections flourished too. The Chinese community in Nagasaki became a cultural and economic bridge. Yet, direct relations with Ming China were off the table—reflecting a highly selective foreign policy.

The Dutch as Japan’s Window to the Outside

The Dutch played a crucial role in keeping Japan informed. Tasked with delivering yearly Oranda Fusetsugaki (Dutch News Letters), they reported global developments back to the Shogunate.

What did these newsletters contain? In the early days, the focus was on Catholic Iberian powers—Spain and Portugal—whom Japan viewed as hardcore geopolitical threats. Think of it as intelligence gathering on “the undesirable neighbors.”

As time went on, news expanded to cover broader European affairs. This included updates on Russian expansion in eastern Siberia, an issue of direct concern to Japan’s northern borders. Surprisingly, the Shogun didn’t limit himself to what affected Japan immediately—the newsletters included coverage of the Great Northern War between Denmark, Poland, Russia, and Sweden (1700-1721). Yes, a kind of Edo-era global newsletter!

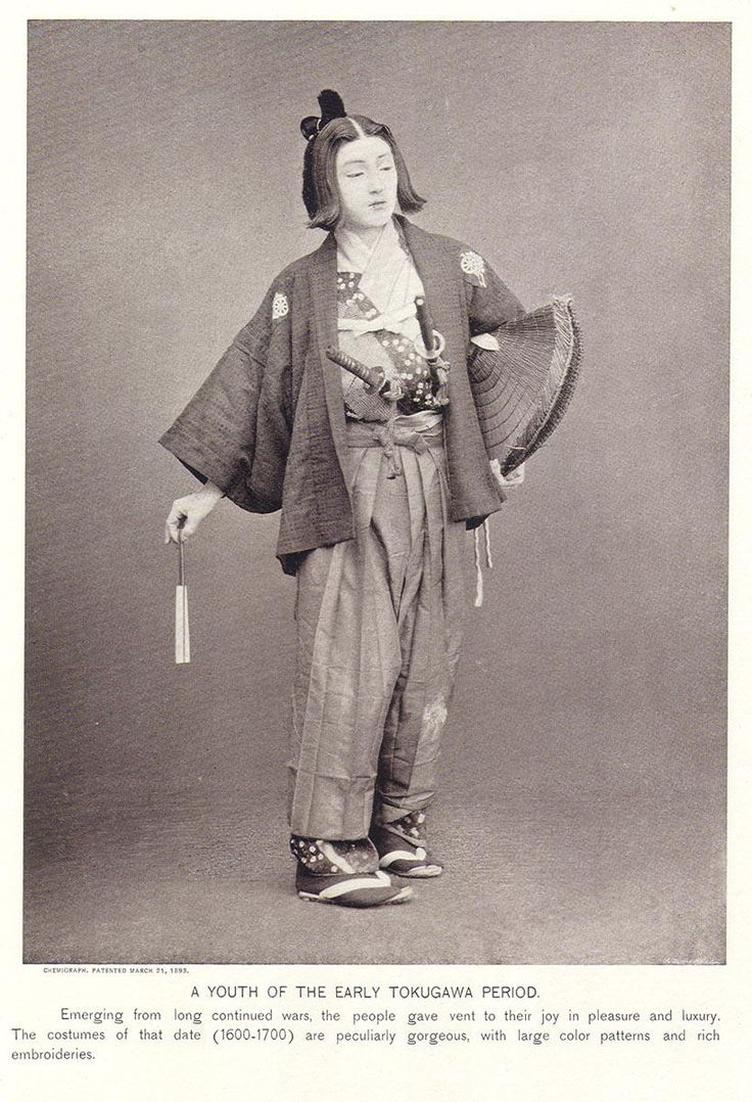

Rangaku: The Blossoming of Dutch Studies

Beyond news, Japan opened the door wider to European knowledge through Rangaku, or Dutch Studies, which gained official sanction around 1720. This intellectual pursuit wasn’t just about knowing who’s fighting whom. It sparked a genuine scientific and literary awakening.

Japanese scholars such as Katsuragawa Hoshu and Honda Toshiaki dove into Western medicine, astronomy, and engineering. They embraced new ideas cautiously—Christianity still remained banned. These intellectual adventures made Edo more plugged-in than previously thought.

Of course, pushing the boundaries sometimes stirred suspicion. Some scholars faced persecution for straying from the Shogunate’s narrative. Still, the overall trend was toward knowledge and curiosity, not strict isolation.

How This All Prepared Japan for Perry’s Ships

When Commodore Matthew Perry sailed into Edo Bay in 1853, Japan faced a shock. But it wasn’t the naive, unprepared shock one might expect. Thanks to the steady trickle of information and Rangaku studies, Japan understood the basics of Western technology and political moves.

The core group of Rangaku scholars became pioneers of rapid modernization after the Meiji Restoration. Japan’s transformation into a world power wasn’t blind—it was built on decades of careful observation and selective engagement.

The Reality of ‘Isolation’—More Like a Carefully Guarded Dialogue

It’s tempting to picture Edo Japan as an island fortress, cut off from the rest of the world. In reality, it’s more accurate to see it as a gardener pruning unwanted branches while nurturing select vines for their fruit.

Restrictions were rigid and security-minded, but diplomacy, trade, and intellectual curiosity flowed through designated channels. Japan wasn’t oblivious. It was choosy. That choice ultimately positioned Japan to leap into modernization with its eyes wide open.

So, What Can We Learn From Edo’s ‘Isolation’ Today?

- Isolation doesn’t have to mean ignorance. Smart gatekeeping can allow for engagement without overwhelm.

- A limited flow of ideas and trade can foster unique cultural development while scanning the horizon cautiously.

- Long-term knowledge-building pays off when rapid change arrives unexpectedly.

Next time you hear “Edo Japan was isolated,” remember this isn’t a story of complete blackout. It’s a tale of calculated contact and measured openness. These details offer a fresh lens—not just for historians, but for anyone balancing openness and protection in a fast-changing world.

How strict were Japan’s maritime restrictions during the Edo period?

Since 1633, Japanese subjects were banned on pain of death from traveling abroad. This policy aimed to control population movement, stop piracy, and prevent the return of banned ideas like Christianity.

Did Edo Japan maintain any foreign relations despite isolation?

Yes. Japan had active diplomatic ties with Korea, Ryukyu, the Ainu, and trade relations with the Dutch East India Company in Nagasaki. They also interacted informally with the Chinese community there.

How did Japan stay informed about the outside world during isolation?

The Dutch in Nagasaki relayed news from Europe through annual reports called Oranda Fusetsugaki. These newsletters covered political events and world affairs relevant to Japan’s interests.

What was Rangaku, and what role did it play in Edo Japan?

Rangaku, or Dutch Studies, was legalized in 1720, allowing scholars to study European science, literature, and history. Christianity remained banned, but Rangaku helped transfer Western knowledge to Japan.

Was Japan truly unprepared for Commodore Perry’s arrival in 1853?

No. Despite the shock, Japan had accumulated knowledge of Western countries and technologies through Rangaku. This groundwork aided rapid modernization after Perry’s visit.