The average Roman citizen was generally functionally illiterate by modern standards, with literacy rates varying from approximately 10 to 15 percent during the Empire’s peak. Literacy was not binary but existed along a spectrum. Most Romans possessed limited reading or writing skills, often restricted to simple, formulaic texts, and professional necessity frequently dictated literacy levels.

Literacy in ancient Rome was complex and differed significantly from today’s concept of fluency. Definitions of literacy include functional literacy—the ability to read and write simple texts—and specialized literacy, which applied to specific professions requiring the understanding of particular documents. Writing often preceded reading instruction, and many learners copied texts without comprehending their meaning. This suggests that many individuals could write without fully understanding what they wrote, a practice distinct from modern literacy.

The Roman world was filled with visible texts, a fact that may imply a higher literacy level than existed. Milestones displayed emperors’ titles and travel distances. Tombstones included names, biographies, and sometimes poetry. Temples used altars and tablets to record vows. Public spaces boasted inscriptions on monuments, calendars, and political advertisements. Markets featured stamps on amphorae indicating contents and origins. Legionaries maintained rosters and wrote letters. Even bricks bore producers’ marks.

This widespread presence of text, particularly the inscription boom in the first three centuries of the Empire, requires assuming some level of literacy. Historian Harold MacMullen introduced the notion of a “sense of audience,” where creators expected their inscriptions to be read and understood by the public. Tombstones, advertisements, and legal inscriptions actively invited audiences to engage by reading texts, indicating that a segment of the population could interpret written language.

Despite this textual ubiquity, assessing the actual literacy rate is challenging due to conflicting evidence. Some scholars argue that literacy was confined to an elite minority and served as a tool for control. This perspective is notably supported by W. Harris, who defines literacy as reading and writing simple sentences with comprehension, setting a high bar for ancient contexts. Harris’s view has shaped modern understanding but may not fit the functional realities of antiquity, where being able to read long texts was not essential for daily life.

Professional requirements influenced literacy significantly. Many Roman citizens learned to read or write mainly to meet vocational needs, such as clerks, slaves managing estates, or legionaries maintaining records. This practical literacy level was often sufficient for operating within Roman society but remained limited in scope and complexity. Stonemasons and scribes, responsible for inscriptions, frequently made spelling errors, implying a lack of comprehensive literacy. These mistakes point to a basic or imperfect understanding of written language rather than full literacy.

Following the fall of Rome, differences in literacy among the common people did not dramatically improve. The breakdown of centralized education and the decline of administrative complexity contributed to maintaining low literacy levels in much of Europe. The transition period preserved many functional literacies centered on local or professional needs, without widespread public education to raise literacy rates substantially. Thus, the common man’s literacy after Rome’s fall remained similar in its limitations, showing continuity rather than dramatic change.

| Aspect | Roman Empire | Post-Rome (Early Medieval) |

|---|---|---|

| General Literacy Rate | 10-15% literate, mostly elites and professionals | Low, limited mainly to clergy and some elites |

| Functional Literacy | Common for vocational purposes, not general education | Similar, focused on local, practical skills |

| Access to Education | No public education, elite or vocational training only | Mostly religious institutions provided learning |

| Written Text Presence | Ubiquitous public inscriptions, graffiti, documents | Declined in volume but preserved in religious texts |

The population’s literacy level depended greatly on social status, occupation, and geographic location. Cities and administrative centers had more literate inhabitants than rural areas. The elite wielded reading and writing as a form of knowledge control and cultural capital.

In summary:

- Most Romans were functionally illiterate by today’s standards, with literacy rates around 10-15%.

- Literacy was a spectrum, often specialized for professions or limited practical use.

- The Roman world featured abundant texts, implying some literacy among the population, but errors in inscriptions indicate basic skills.

- After Rome’s fall, literacy levels among common people remained low, sustained mostly by religious institutions.

- Elite dominance over literacy presented it as a tool for social control rather than widespread education.

How Literate Was the Average Roman Citizen? Exploring Literacy Across Rome’s Rise and Fall

Simply put: the average Roman citizen was, by modern standards, mostly illiterate, with only about 10 to 15 percent meeting what we would consider literate. But that answer alone doesn’t tell the whole story. Literacy in ancient Rome was a complex, layered phenomenon, varying based on time, place, class, and purpose.

So, what was it like to read or write in Rome? How did literacy shift as the empire rose and eventually stumbled into the so-called Dark Ages? And did common folks lose more reading skills than just the empire itself? Let’s unpack these questions.

The Spectrum of Literacy: More Than Just Literate or Illiterate

Unlike today’s black-or-white definitions, literacy in the Roman world wasn’t a simple “can read and write” or “can’t.” Instead, literacy was a continuum.

- Some Romans could sign their names and read simple signs. Others understood specialized texts tied to their occupation.

- Then there were elites fluent in complex literature, legal documents, and philosophical texts—true scholars of the written word.

Think of it like this: If today’s modern literacy requirement includes reading news articles and emails, a Roman might have survived with the equivalent of a postcard-level literacy.

Writing itself was often taught before reading. Students practiced scribbling verses or statements without fully grasping the words—more rote repetition than understanding.

Text Everywhere: The Ubiquity of Writing in the Roman Empire

If you were to stroll through ancient Rome during its peak, you’d be swimming in text. Streets and walls were plastered with writing like social media feeds but in stone or ink.

- Milestones handed out distances and emperor’s fancy titles.

- Tombstones lined roads, telling stories, sometimes urging passers-by to pause and reflect: “Stop, traveller, and read!”

- Triumphal arches boasted victories and generosity.

- Markets buzzed with labels, stamps on amphorae, and graffiti—some quite raunchy.

Even everyday objects bore inscriptions. Bricks carried maker’s marks. Legionaries jotted duty rosters and inventory lists. Private homes labeled possessions. The amount of surviving texts—from papyri in Egypt to wooden tablets in Britain—showcases how deeply writing permeated life.

This boom in inscriptions, especially in the first three centuries of the empire, suggests that literacy, or at least some reading awareness, must have been widespread enough to justify such efforts.

Audience Expectation: Romans Expected People to Read

Historian MacMullen coined the idea of a “sense of audience.” Romans didn’t just carve words randomly. They expected someone to read and understand those inscriptions.

Why else would an epitaph recall a deceased’s virtues or a political announcement broadcast campaign promises? The texts actively engaged readers—indicating some literate or semi-literate population.

On the flipside, some scholars argue that the elite controlled literacy tightly, using it as a secret tool of power to confine knowledge and preserve social hierarchy.

Challenges in Pinning Down Roman Literacy

Despite all these texts, how many Romans truly read and understood them? The evidence often conflicts.

W. Harris, a major figure in ancient literacy studies, defines literacy as the ability to read and write a simple sentence with comprehension—already a high bar for the Roman world.

Modern literacy assumes reading lengthy books or newspapers. Rome didn’t require that standard.

Even those carving inscriptions often lacked full literacy. Frequent spelling errors—like swapping letters or doubling them—show not all stoneworkers grasped the meanings of their texts.

Functional Literacy: Just Enough to Get By

Most Romans learned to read and write only as much as their job demanded.

- Legionaries kept duty rosters.

- Slaves working on aristocratic estates learned simple record-keeping.

- Merchants and craftsmen used labels and receipts regularly.

This kind of rudimentary, or specialized, literacy helped people operate in their world without fully mastering the written language.

It’s like knowing social media shorthand instead of reading a novel—enough to communicate and survive but not to dive deep into literature.

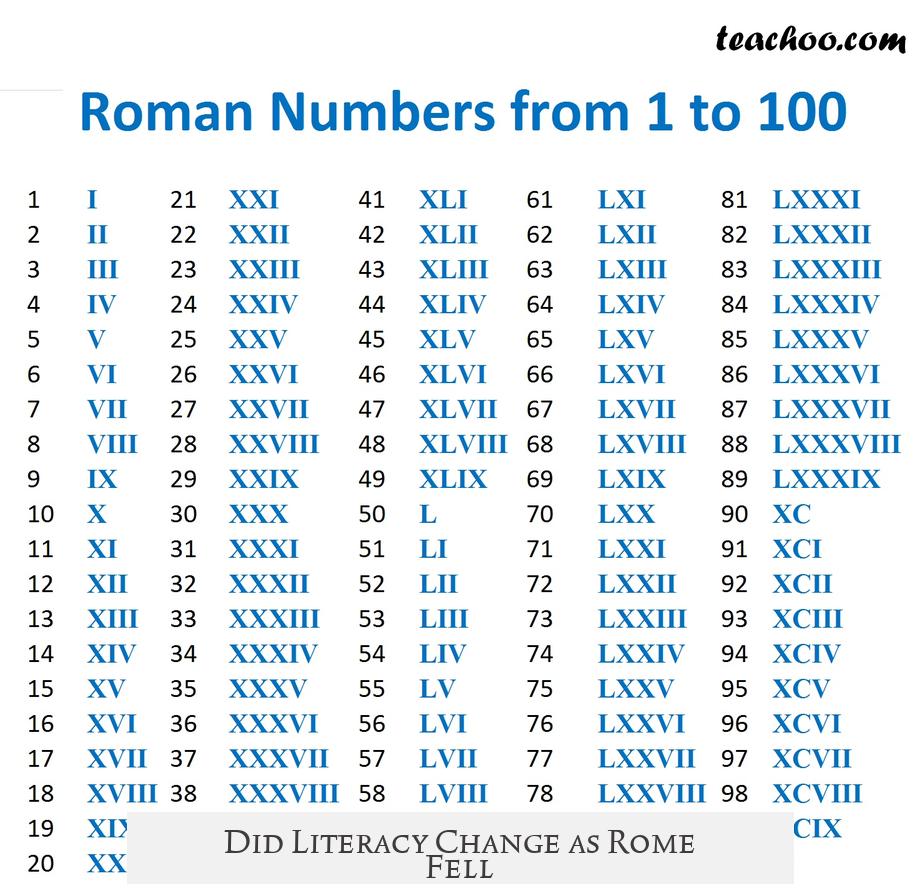

Did Literacy Change as Rome Fell?

What about after Rome’s fall, the transition into the Middle Ages? Did common folk suddenly become illiterate? The story gets fuzzy here.

Some assume literacy dramatically declined after the empire crumbled. However, the reality is more nuanced:

- Continuity with disruption: Literacy likely dipped among cities due to political chaos and the breakdown of formal education systems.

- Barbarian rule and Christian monasteries: New rulers often lacked urban sophistication, but Christian monks preserved and sometimes spread literacy through scriptoria (copying manuscripts).

- Rural literacy: Most “common” people remained functionally illiterate before, during, and after Rome’s fall—reading was never widespread in rural areas.

Thus, **the big jump down in literacy wasn’t necessarily a cliff—more a slow fade, intertwined with social and economic shifts.** It’s a mistake to imagine every peasant was suddenly illiterate post-Rome when in fact, many never had reading skills to begin with.

Why Does This Matter? Lessons from Roman Literacy

The Roman case teaches us about literacy’s many faces—not a binary but a spectrum shaped by need, status, and context.

- Texts won’t be effective if no one understands them; so some audience had basic literacy.

- Specialized literacy shows how education can be vocational and limited—not everyone must read Shakespeare to be “literate.”

- The presence of graffiti and public notices shows literacy at all social levels, though uneven and limited.

- Social hierarchies can affect who learns to read and write, and who doesn’t.

Imagine if you only needed to recognize a few words or symbols to navigate your town, work, and social life. That’s pretty much the ancient Roman scenario for the average citizen.

In Summary

| Aspect | Roman Reality |

|---|---|

| Average literacy rate | 10-15% by modern standards |

| Literacy type | Functional, specialized; complex literacy limited |

| Text presence | Ubiquitous in public and private life |

| Audience | Expected to read inscriptions, advertisements, official texts |

| Post-Rome literacy | Declined but not collapsed; rural illiteracy remained high |

So, next time you wonder about ancient Romans reading their graffiti or tombstones, remember: many could read enough to make sense of their world, but few mastered the art of full literacy as we understand it today. Their literacy suited the needs of their time—simple, practical, and diverse.

In the great story of Rome, literacy wasn’t a privilege of the elite alone. It was a patchwork quilt of skill levels, intended for everyday urban life as much as for administration or philosophy.

Now, wouldn’t it be fun to imagine a Roman citizen puzzling over how to read your latest social media status? They’d probably manage a hashtag or two—but diving into your whole feed? That might take more than their ancient “functional literacy.”