The Nazi salute originated from the Fascist salute popularized by Benito Mussolini’s Italian Fascist Party, not directly from ancient Rome. This gesture, known as the Roman salute, was later adopted by the Nazis to symbolize loyalty and unity, borrowing from Italian Fascism’s imagery and political style.

The salute involves raising the arm straight outwards with fingers together and palm down. Mussolini embraced this gesture to evoke the authority of ancient Rome, aligning it with his vision of a new Italian empire. The Fascist name itself is derived from the Latin “fasces,” an ancient Roman symbol representing power and jurisdiction.

Sources state that the Italian Fascist salute was influenced by earlier nationalist uses, particularly the proto-Fascist Gabriele D’Annunzio. D’Annunzio employed the salute during his brief control of the city of Fiume in the early 20th century. His adoption of the gesture helped embed it into the nationalist and Fascist lexicon before Mussolini officially implemented it.

However, the claim that the salute was authentically Roman is debatable. Archaeological and artistic evidence does not support the existence of this specific gesture in Roman antiquity. No known Roman texts or artworks depict the modern Fascist salute accurately.

Some Roman artworks show raised hand gestures but differ in finger positioning or arm posture. For example, Trajan’s Column shows salutes with splayed fingers, not the tight fingers seen in the Fascist salute. The statues often misidentified with the salute, such as Augustus of Prima Porta and Marcus Aurelius on the Campidoglio, do not actually present this specific gesture. The arm position in Augustus of Prima Porta is a restoration, originally holding a spear, while Marcus Aurelius’ gesture is best understood as a benediction.

The strongest candidate for the modern salute’s origin is the 18th-century painting The Oath of the Horatii by Jacques-Louis David. In this neoclassical work, three brothers raise straight arms with fists tightly clenched fingers to their father while swearing an oath. This gesture is stylized and does not reflect genuine Roman customs but was designed by David to symbolize loyalty and unity powerfully.

The painting’s salute conveys civic and filial devotion forcibly and dramatically. It diverged from earlier, more restrained depictions of Roman subjects and oath-taking scenes. Contemporary critics admired the emotional force and symbolism in the gesture, which influenced later artworks, including David’s The Tennis Court Oath and Jean-Léon Gérôme’s The Death of Caesar.

Napoleon further adapted this gesture in his artworks. For instance, in The Distribution of the Eagle Standards (1810), commanders raise their hands similarly to the Horatii, pledging loyalty to the Emperor. This use subtly shifted the gesture’s meaning towards imperial authority, extending its legacy from neoclassical art into political symbolism.

The Fascists, then, revived a stylistic invention from art history as a political tool. The Nazis followed this pattern, taking the Italian Fascist salute and embedding it into their own identity to project strength, unity, and reverence for hierarchical loyalty. While called the “Roman salute,” it stands as a modern invention rooted more in political imagery than historical fact.

| Source | Contribution |

|---|---|

| Italian Fascists | Popularized the salute as a symbol of Fascist loyalty based on Roman imagery. |

| Gabriele D’Annunzio | Proto-Fascist who used the salute in nationalist demonstrations. |

| Jacques-Louis David | Created the artistic model for the salute in The Oath of the Horatii. |

| Napoleon | Amplified the gesture’s imperial symbolism in military oath artworks. |

| Nazis | Adopted the Italian Fascist salute as part of their propaganda and identity. |

- The Nazi salute derives from the Italian Fascist salute, not ancient Rome.

- The salute’s “Roman” character is an 18th-century artistic invention, popularized by Jacques-Louis David.

- Mussolini used the salute to evoke Roman imperial power and unity.

- Art and history show no evidence the exact salute existed in Roman times.

- The gesture evolved as a political symbol linked to loyalty and nationalism.

Where Did the Nazi Salute Come From?

The Nazi salute did not just burst onto the scene from the twisted mind of Hitler’s regime. It was borrowed, adapted, and evolved from previous gestures—most notably the Italian Fascist salute under Mussolini.

So, why is the Nazi salute shaped the way it is? And how did it become such a powerful symbol? Let’s unravel the origins, debunk some myths, and reveal its artistic and political roots.

The Italian Fascist Connection: Borrowing a Gesture

The Nazi salute wasn’t a spontaneous invention. The Nazis adopted what was known as the “Fascist Salute,” popularized by Italy’s Mussolini and his Fascist Party well before Hitler’s time.

Mussolini was obsessed with linking modern Italy to the grandeur of the Roman Empire. Fascism, after all, gets its name from the Latin word fasces—those iconic bundles of rods symbolizing power and unity in Ancient Rome.

The salute itself mirrors what is often called the Roman Salute: the arm extended outward, fingers together, palm down. It was meant to evoke an aura of strength and unity as the “New Rome” brand of Fascism was being crafted.

This salute was not unique to Italy; other Fascist-aligned groups like the Spanish Falangists also adopted it. It was shared symbolism among early 20th century European authoritarian movements.

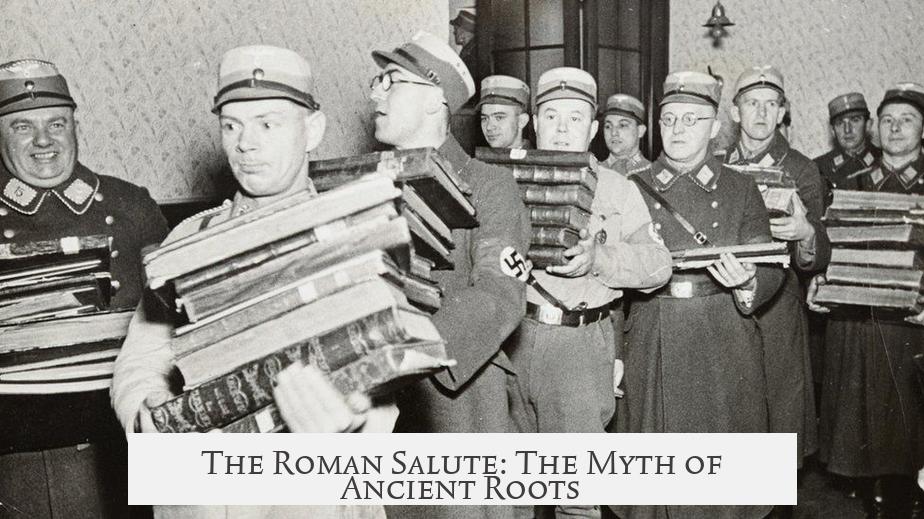

The Roman Salute: The Myth of Ancient Roots

Here is the kicker: the so-called Roman Salute is not authentically Roman.

Careful examination of ancient Roman art and texts reveals no evidence of the outstretched, palm-down arm gesture we associate today with Fascism or Nazism.

Trajan’s Column, one of the richest sources of Roman military imagery, shows raised arms—but with fingers spread, not tightly together.

The iconic statue Augustus of Prima Porta, sometimes mistaken as giving the Roman Salute, doesn’t actually do so. The raised arm is a later restoration holding a spear, not a salute.

Even the Equestrian Statue of Marcus Aurelius, once claimed by Fascists as offering the Roman Salute, is more likely showing a gesture of blessing or peace—if you catch it from just the right angle.

The Real Origin: An 18th Century Painting

If it’s not Roman, then where?

The gesture’s true, documented origin lies in the late 18th century, with the neoclassical painting The Oath of the Horatii by Jacques-Louis David. It depicts three brothers swearing an oath to their father—a dramatic moment of loyalty and sacrifice.

David painted the brothers with their arms stretched straight out, fingers together and palms down—creating a powerful visual symbol of unity and commitment.

Of course, this scene is a dramatic invention. The story itself is based on semi-mythical Roman lore, and David used this salute to evoke a sense of civic devotion and moral purpose.

Before David, depictions of Roman oaths appeared far less dramatic. His rendering injected a new level of intensity and style into classical virtue. It became a template for “heroic” gestures in art.

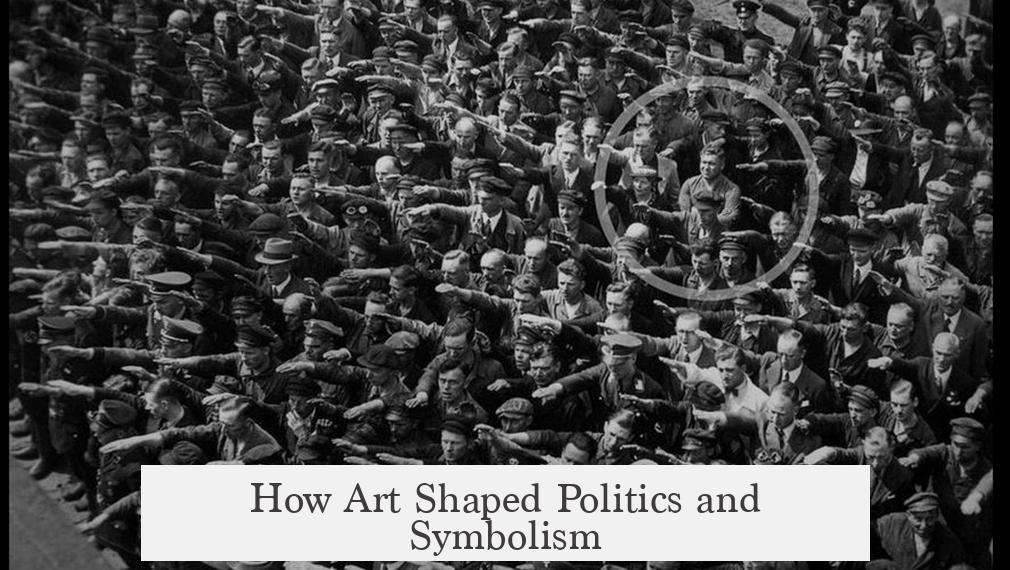

How Art Shaped Politics and Symbolism

Critics in David’s time marveled at his bold composition. The artistic choice of the salute captured a new way to show allegiance—a visual shorthand for loyalty and unity that resonated deeply.

This influence extended beyond painting. Artists like Jean-Léon Gérôme echoed it in later works such as The Death of Caesar. The upward stretched arms with weapons raised could be traced back to David’s powerful style.

David himself reused the gesture in his depiction of the French Revolution’s Tennis Court Oath—linking ancient and modern political loyalty in one dramatic image.

The Gesture Becomes Political Propaganda

By the early 19th century, under Napoleon, the gesture appears again but with a new message of imperial obedience. In The Distribution of the Eagle Standards (1810), military commanders pledge loyalty using that same extended arm, now framed as an oath to an empire rather than a republic.

National symbolism was shifting. The gesture came to symbolize not just unity but centralized power and authority.

Seeing Blackshirts or Nazi soldiers performing this salute in the 20th century, you can recognize the lineage—from David’s neoclassical art to Mussolini’s fascism, and then into a dark chapter of history with Nazi Germany.

Why Does This Matter?

Understanding the origin of the Nazi salute exposes some uncomfortable truths:

- It wasn’t a spontaneous or “ancient” Roman tradition as claimed by Fascists and Nazis.

- It was a carefully crafted symbol designed to evoke power, unity, and loyalty.

- Art and political propaganda intertwine in complex ways.

Knowing the history strips some of the mythic power the salute tries to wield. It reminds us to question symbols and their origins instead of accepting them at face value.

Practical Takeaway: Recognizing Power in Simple Gestures

Next time you see someone impersonate this salute or reference it in films or politics, you can recognize its layered history. It’s not just a stiff-armed wave but a symbol packed with centuries of artistic invention and political messaging.

This salute teaches us how culture, art, and political ideology can blend to create symbols that influence masses—sometimes for good, often for terrible ends.

Whether in classrooms, museums, or cafes, bring up this story to challenge simplistic notions about history, art, and power. Not every tradition is as old or authentic as it looks.

In Conclusion

The Nazi salute has roots far removed from ancient Rome. It travels through Italian Fascism and neoclassical art before being adopted by Nazi Germany. Its journey is a reminder that symbols aren’t always what they seem.

The salute’s potency comes not from age-old tradition but from deliberate invention and adaptation. By exposing this, we take a critical step toward understanding how history and art shape our political realities.

So, next time you see that stiff-armed greeting, remember: it’s a gesture born in a painting, molded by imperial ambition, and twisted into a symbol of totalitarian rule.

Who knew art class and history lessons could be so relevant to understanding one of the 20th century’s darkest symbols?