Native American civilizations known as the Mound Builders were not a single culture but a broad grouping of diverse societies across eastern North America, spanning over 5,400 years. These groups built earthen mounds for varied purposes and evolved through multiple cultural phases rather than existing as one continuous entity.

The term “Mound Builders” broadly describes multiple cultural traditions rather than one. Mound construction waxed and waned through time. Different groups built mounds for burial, ceremonial, defensive, or residential purposes depending on the era and location.

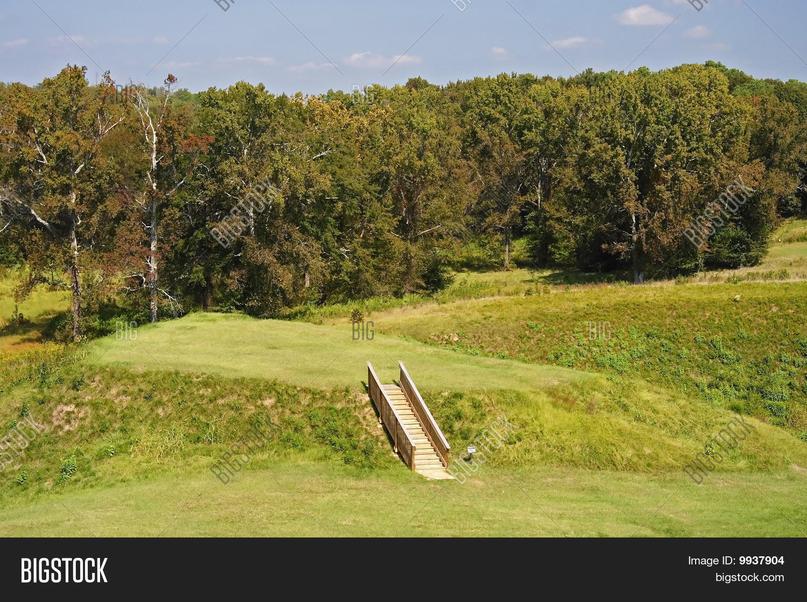

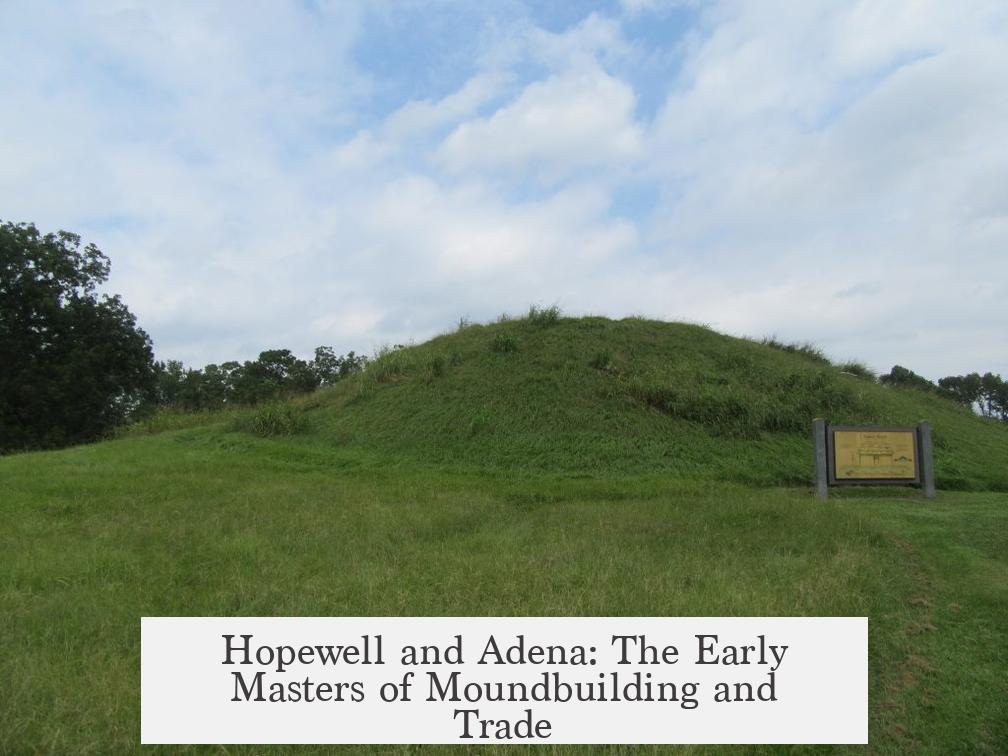

One of the earliest significant mound-building complexes were the Hopewell traditions, flourishing approximately 200 BCE to 400 CE in the Ohio and Mississippi River valleys. These were not a single nation but a network of related societies. The Hopewell culture developed extensive trade routes over hundreds of miles. Their society focused on peace, ritual mounds, and elaborate earthworks, reflecting complex social structures and cosmology.

The Hopewell period ended around 400 CE when social patterns shifted. People became more isolated and defensive structures appeared. Trade networks tightened to local goods, ceremonial activities declined, and the atlatl weapon was replaced by the bow and arrow. This change might relate to migrations by Algonquian groups moving southward into the region, though the exact causes remain uncertain.

Between roughly 600 and 900 CE, the Emergent Mississippian culture arose from post-Hopewell societies. Centered initially in the middle Mississippi Valley near present-day Missouri and Illinois, this culture intensified maize agriculture. Maize became the dominant crop, supplanting most of the previous Eastern Agricultural Complex, except squash and sunflowers.

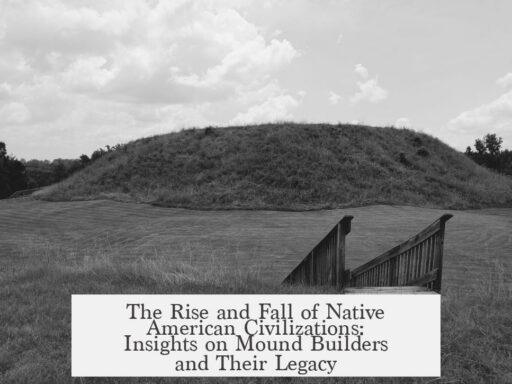

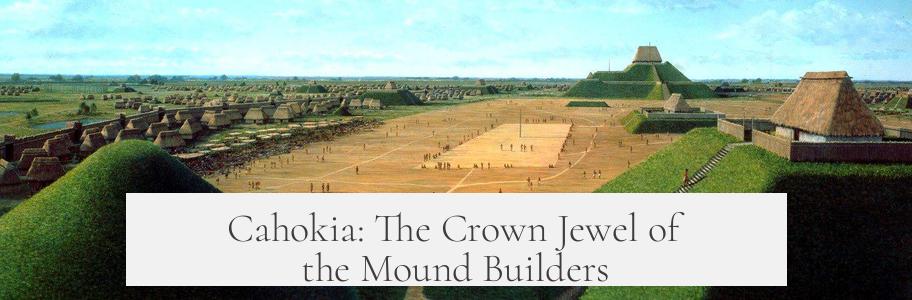

The pinnacle of Mississippian culture is represented by Cahokia, founded around 900 CE in the Mississippi River floodplain near today’s St. Louis. By 1050 CE, Cahokia boasted monumental construction, including Monks Mound, the largest pre-Columbian earthwork north of Mexico. It housed possibly 20,000 to 40,000 residents, making it one of North America’s largest urban centers at the time.

Cahokia’s influence extended widely, with smaller contemporaneous sites such as Etowah in Georgia and Spiro in Oklahoma. The civilization featured hierarchical leadership, extensive trade, and complex religious practices.

By around 1200 CE, Cahokia’s population declined. This collapse coincided with the Great Drought, a prolonged environmental crisis affecting large parts of North America. The drought likely stressed agriculture and resource availability.

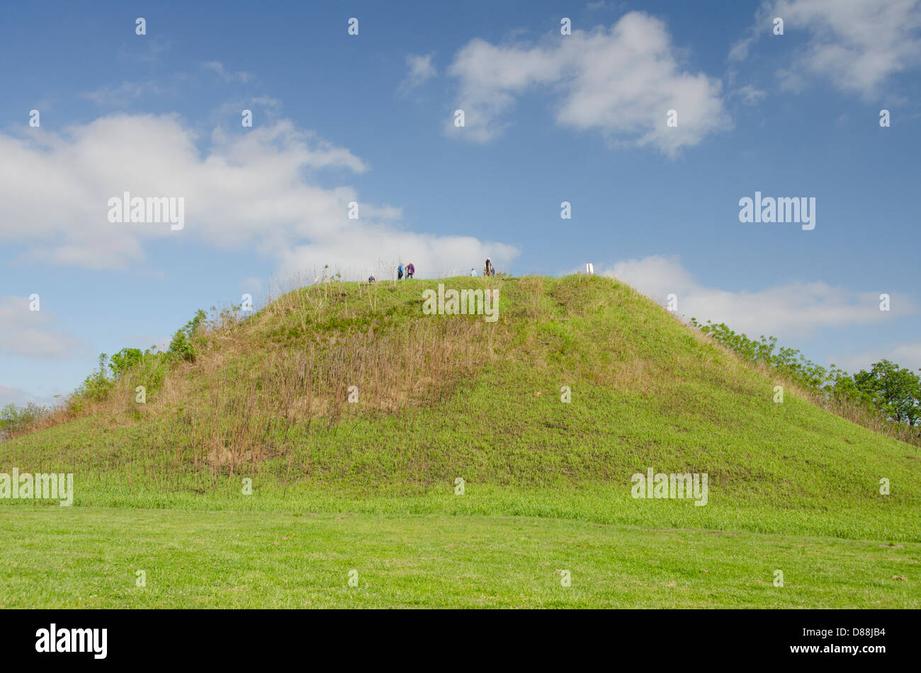

Rather than vanishing, Cahokia’s population gradually dispersed into smaller settlements spread across the region. Nearby sites like Angel Mound in Indiana grew in prominence as Cahokia waned. Angel Mound thrived until roughly 1450-1500 CE, when an earthquake led to its abandonment and transition into the Caborn-Welborn culture. This culture survived into early European contact times but left limited records.

Other Mississippian groups in the lower Mississippi Valley and the southeastern U.S. persisted well beyond Cahokia’s decline. These included the Plaquemine Mississippians and the South Appalachian Mississippians, communities that maintained complex social hierarchies, mound construction, and trade networks until European arrival.

- The Apalachee in northern Florida held significant cities such as Lake Jackson and later Anhaica and Ivitachuco, with populations estimated around 36,000 by 1500 CE. However, disease and raids devastated these populations during the 1600s.

- The Creek Confederacy, evolving from Mississippian chiefdoms such as Coosa, remained influential in northern Georgia and Alabama through the 18th century. Coosa was powerful when first contacted by Europeans during Hernando de Soto’s expedition in the 1540s.

Many historic tribes trace their origins to these Mississippian cultures. The Choctaw descend from the Tuscaluza/Atahachi, the Chickasaw from the Chicaza, and the Natchez maintained mound building and leadership traditions until the early 18th century. The Natchez Revolt against the French in 1729 marked one of the last prominent expressions of Mississippian culture before European domination reshaped indigenous societies.

The narrative that Mississippian civilizations disappeared abruptly is inaccurate. While population centers and political structures changed due to environmental, social, and colonial pressures, many of these peoples adapted. They dispersed, merged, or evolved into new political entities. Mississippian cultural traits like mound building, hierarchical chiefdoms, and trade networks endured in various forms.

| Culture / Period | Timeframe | Characteristics | Notable Sites |

|---|---|---|---|

| Hopewell Traditions | ~200 BCE – 400 CE | Peaceful trade networks, ceremonial mounds, diverse societies | Ohio and Mississippi River valleys |

| Mississippian Culture | 600 CE – European contact | Maize agriculture, mound building, hierarchical chiefdoms | Cahokia, Etowah, Spiro, Angel Mound |

| Caborn-Welborn Culture | Post-1450 CE | Continuation after Angel Mound, early European contact | Lower Ohio Valley |

| Historic Tribes (Creek, Choctaw, Chickasaw, Natchez) | Post-Contact – 18th Century | Mississippian descendant chiefdoms | Southeastern US |

Overall, Native American mound-building civilizations represent a complex archaeological and cultural tapestry. Different groups built mounds for centuries with varying goals. Their civilizations evolved in response to environment, migration, and contact pressures. During colonial intrusion, many Mississippian descendants persisted as key indigenous nations, preserving traditions and culture.

- “Mound Builders” refers to many distinct cultures, not one single group.

- Hopewell cultures (~200 BCE–400 CE) fostered trade and ceremonial mound-building in peace.

- Mississippian culture (~600 CE onward) emphasized maize agriculture and large mound complexes like Cahokia.

- Cahokia declined around 1200 CE due to megadrought; populations scattered into smaller settlements.

- Other Mississippian societies persisted into historic times, evolving into tribes like the Creek, Choctaw, Chickasaw, and Natchez.

- These groups adapted rather than disappeared, maintaining core Mississippian cultural elements.

What Happened to Native American Civilizations Like the Mound Builders and What Was Their Civilization Like?

Short answer: The so-called Mound Builders were not one single group but a tapestry of diverse, evolving Native American cultures who thrived for thousands of years—building mounds for different reasons, creating vast trade networks, and establishing complex societies—before gradual shifts, migrations, and environmental challenges changed their ways of life. Their civilizations didn’t just vanish; they adapted, dispersed, merged, and persisted in new forms well into European contact.

So, who exactly were the Mound Builders? And what became of their fascinating civilizations? Grab a comfy chair and keep reading—this story is as winding and rich as the mighty Mississippi itself.

The Myth of “The Mound Builders” – A Label That Lost Its Meaning

To get started, it’s important to bust a common misconception. The “Mound Builders” aren’t a single tribe or monolithic civilization. The term lumps together numerous indigenous cultures across eastern North America over a mind-boggling span of 5,400 years. Imagine using one label for all rock bands ever—Queen, Nirvana, Coldplay—it just doesn’t work.

Mound-building emerged, disappeared, and re-emerged multiple times. Its purpose was just as varied: some mounds were burial sites, others were ceremonial platforms, and some marked settlements or defensive areas.

- Different cultures with distinct languages and customs built mounds for different reasons.

- The practice waxed and waned across millennia, shifting according to social and environmental conditions.

- This diversity and adaptability is key to understanding their legacy.

Hopewell and Adena: The Early Masters of Moundbuilding and Trade

Zooming in around 200 BCE to 400 CE, the Hopewell traditions flourish mainly in the Ohio and Mississippi valleys. Yet, don’t mistake Hopewell for a single nation—it’s more like a family of related tribes with shared cultural threads.

Their society prizes peace, expansive trade routes, and magnificent ceremonial mounds. They traded exotic materials like obsidian and mica across great distances, building connections far beyond their homeland.

But around 400 CE, things take a turn. Defensive mounds replace the old ceremonial ones. Atlatls, spear-throwers popular for hunting, give way to bows—arguably a technological upgrade. Trade networks shrink, and the once vibrant cultural tapestry shows signs of unraveling, possibly influenced by waves of Algonquian migration from the north.

Mississippian Culture: The Maize Revolution and Urban Rise

Fast forward a few centuries to between 600 and 900 CE, and the Mississippian culture emerges, starting in present-day Missouri and Illinois. A defining trait? Maize—or corn—takes the spotlight as the main crop. It replaces many earlier cultivated plants, though squash and sunflowers persist as nostalgic favorites.

This agricultural boom supports larger populations and complex societal structures. The transition is not sudden but a gradual fusion of older traditions with new innovations. With these changes comes renewed mound building and the rise of urban centers.

Cahokia: The Crown Jewel of the Mound Builders

Around 900 CE, mound building blooms anew at Cahokia, near present-day St. Louis. By 1050 CE, they start building Monks Mound, a colossal earthen structure still awe-inspiring today. At its peak, Cahokia hosts 20,000 to 40,000 people, making it one of the biggest cities north of Mexico.

- Cahokia features an intricate layout of plazas, mounds, and wooden structures.

- It isn’t alone; satellite settlements like St. Louis, Etowah in Georgia, and Spiro in Oklahoma weave into this regional network.

- Trade, religion, and politics intersect in a highly organized society.

Life at Cahokia is vibrant but complex. Leaders wield significant control, orchestrating communal efforts to build and maintain monumental architecture. The culture emphasizes ritual and reverence for the cosmos, intertwined with agricultural cycles.

What Happened to Cahokia and Others? Decline, Dispersal, and Transformation

By about 1200 CE, Cahokia begins to fade. Historians link this to the Great Drought, an extended dry spell across North America coinciding with Europe’s Medieval Warm Period. Crops likely suffered, challenging urban sustainment.

But don’t picture an abrupt apocalypse or vanish act. Instead, the population trickles out, spreading into adjacent areas. Nearby communities grow and shrink in a kind of population shuffle, rather than disappearing into thin air.

A fine example is Angel Mound in Indiana, emerging around 1100 CE and gaining prominence as Cahokia wanes. Angel flourishes for centuries until an earthquake and shifting cultural tides force abandonment around 1450–1500 CE. Its people move into the Caborn-Welborn culture, which survives into the early European contact period—offering a living thread of Mississippian heritage.

Mississippian Offshoots: Persistence Beyond Cahokia

While Cahokia’s star dims, other Mississippian societies keep shining. The Plaquemine Mississippians in the lower Mississippi Valley and South Appalachian Mississippians spread across Alabama, Georgia, South Carolina, and northern Florida.

Some of these cultures build cities as large or larger than Cahokia. The Appalachee in northern Florida, around 1500 CE, have a capital at Lake Jackson adorned with numerous mounds. Later shifting capitals do not continue mound building but hold onto other Mississippian traits.

By 1608, the Appalachee population reaches an estimated 36,000. However, European-introduced smallpox and slave raids by English-allied Creek Confederacy deal severe blows during the 1600s.

The Creek Confederacy itself emerges as a powerful force in northern Georgia. By the 1540s Spanish expedition of Hernando de Soto, the Coosa chiefdom dominates a vast region. Coosa faces decline after European contact but rebounds to thwart further colonization attempts before becoming part of the Creek Confederacy in the 1700s.

Modern Descendants of Mississippian Societies

The cultural legacy lives on in several Native American nations today. The Choctaw trace roots to the Tuscaluza/Atahachi groups; the Chickasaw descend from the Chicaza; and the Natchez hold direct Mississippian heritage, famously clinging to mound-building traditions into the 18th century.

The last major Mississippian polity, the Natchez, survives until 1729, when a revolt against French colonial forces ended their autonomous tribal structures. Despite this, their cultural memory and artifacts remain, preserving the rich traditions crafted over centuries.

More Than Decline: Adaptation and Resilience

It’s misleading to say these civilizations simply vanished. Many chiefdoms declined for various reasons—environmental, social, or external pressures—but others persisted, adapted, or merged into new forms.

Trade routes shifted. Political centers moved. Some societies transformed their architecture; others preserved their ways beneath new political realities. Not all who lived on mounds forgot how to build them.

As articulated by historians, “There is no neat ending. These cultures evolved, survived contact, and their footprints echo in the descendants who still honor parts of their Mississippian past.”

Why Does This Matter in 2024?

Understanding these civilizations broadens how we see Native American history beyond simplistic narratives of “disappearance.” The Mound Builders show us complex societies with far-reaching networks and achievements.

With archaeological sites like Cahokia gaining UNESCO World Heritage recognition and Native nations revitalizing their histories, this knowledge is vibrant and important today.

How do we honor these legacies fairly? It starts by ditching outdated labels, recognizing diversity, and acknowledging resilience—a story still unfolding.

Final Thoughts: Digging Deeper Than the Dirt Mounds

So next time you hear “Mound Builders,” remember it’s shorthand for much more—thousands of years of innovation, culture, trade, and adaptation.

These Native American civilizations were no strangers to change. They built great cities, endured massive challenges, and left marks on American history that deserve both respect and curiosity.

Feeling curious? Explore sites like Cahokia, Angel Mound, or the Grand Village of the Natchez online or in person. The past is a living story just waiting to be told—and retold.

- Grand Village of the Natchez – Explore their enduring heritage.

- The Natchez Indians – Learn about their cultural persistence post-European contact.

- Mississippian chiefdom decline discussion – For a nuanced take on transitions.

What would you want to know next about Native American cultures? Which mysteries would you love to see archaeology uncover?

What were the Mound Builders and why is the term considered outdated?

The term “Mound Builders” refers to various Native American cultures who built earthen mounds over 5,400 years in eastern North America. It is outdated because it groups many distinct, unrelated peoples and diverse mound-building practices under one label.

What led to the decline of the Hopewell culture around 400 CE?

The Hopewell culture declined as communities became more isolated and defensive. Trade networks shrank, fewer ceremonial mounds were built, and new weapons appeared. This may be linked to migrations from northern Algonquian peoples.

What was significant about Cahokia in Mississippian culture?

Cahokia was the largest Mississippian city, built around 900 CE, with a population of 20,000 to 40,000. It featured large mound constructions like Monks Mound and served as a political and cultural center in the Mississippi Valley.

Why did Cahokia decline after 1200 CE and what happened to its population?

Cahokia declined due to the Great Drought, an environmental crisis. Rather than disappearing, its population spread into smaller communities nearby, leading to more dispersed settlements across the region.

Did Mississippian cultures survive European contact?

Yes. Some Mississippian societies, like the Caborn-Welborn culture, persisted into early European contact. Though their historical records are limited, archaeological evidence shows they continued trading and adapting during this period.