The term “Dark Ages” is considered a misnomer because it inaccurately represents the period in European history following the fall of the Western Roman Empire as a time of pure decline and ignorance. This label oversimplifies complex developments and ignores significant achievements in both the Byzantine Empire and Western Europe during the Middle Ages.

The common understanding portrays the era after AD 476, when the Western Roman Empire fell, as a sudden plunge into chaos and cultural darkness. People imagine a Europe where education, culture, and science ceased, replaced by barbarism and stagnation. This stereotype is largely exaggerated and incorrect. It neglects the fact that civilization did not vanish overnight but continued evolving in many domains.

The fall of the Western Roman Empire is often wrongly framed as the end of European civilization. However, the Byzantine Empire, essentially the Eastern half of the Roman Empire, thrived for another thousand years. It stood as a Mediterranean superpower, advancing science, technology, philosophy, theology, and medicine. Recent scholarship corrects Western biases that previously downplayed Byzantine achievements due to long-standing animosity.

Meanwhile, Western Europe was not as backward as often claimed. After a short phase of adjustment to the empire’s collapse, new kingdoms and political structures emerged. The Merovingians, Lombards, and ultimately the Holy Roman Empire laid foundations for future European states. This period fostered growth, consolidation, and cultural development rather than outright decay.

The presumed sharp break between the Middle Ages and the Renaissance is also a misconception. Renaissance achievements were built on developments of prior centuries, many rooted in Byzantine scholarship from the 10th to 12th centuries. So, the Renaissance should be seen as an evolution and culmination, not an abrupt revival from a “dark” void.

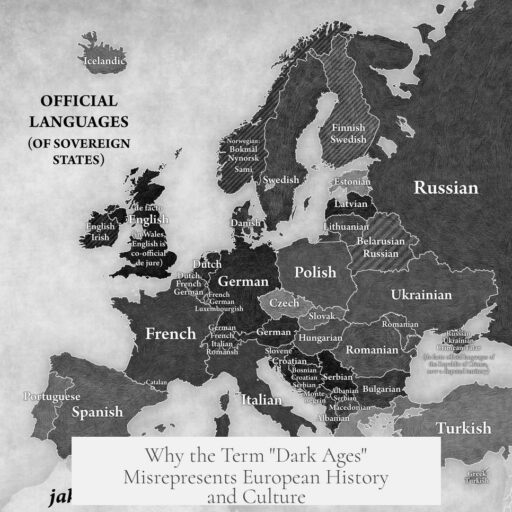

Another false narrative involves the preservation of Greco-Roman texts. The idea that Muslims alone saved ancient knowledge and reintroduced it to Europe ignores the Byzantine role. Byzantium preserved over a million volumes of classical works in institutions like the Pandidakterion and the Great Library of Constantinople until 1204. When the Muslim Caliph al-Mamun requested texts, the Byzantines supplied them, which helped Islamic scholars study and expand upon the classical legacy.

Through Byzantine trade networks, Italian maritime states had access to these works well before the famous “reintroduction” of Arabic translations via centers like the Toledo School in Spain during the late Middle Ages. Muslim scholars notably advanced mathematics and science, but their role complemented Byzantine preservation rather than replacing it.

The term “Dark Ages” merges many centuries into a broad, unjust judgment. It overlooks Byzantine achievements and Western Europe’s resilience. Applying this term promotes ignorance and perpetuates outdated biases rooted in historiographical traditions that modern research has challenged and refined. Many intelligent and innovative figures contributed to cultural and intellectual progress during this time.

Ultimately, calling this era the “Dark Ages” misrepresents a millennium of history marked by complexity, continuity, and growth. It unfairly diminishes the efforts of societies that maintained and transmitted knowledge, fostered new institutions, and laid the groundwork for Europe’s later transformations.

- The “Dark Ages” label exaggerates decline and ignores progress after the fall of Western Rome.

- The Byzantine Empire preserved and advanced classical knowledge for centuries.

- Western Europe formed new kingdoms and continued development, countering the idea of collapse.

- The Renaissance evolved from Middle Age and Byzantine advancements, not from darkness.

- Preservation of Greco-Roman texts was a combined effort of Byzantines and Muslims.

- Using “Dark Ages” promotes ignorance and outdated views, undermining scholarly evidence.

Why Are the European “Dark Ages” Considered a Misnomer?

Simply put, the term “Dark Ages” is a misconception that unfairly smears an entire millennium-plus of European history as backwards and uncultured, when in reality, it was a time of resilience, development, and preservation of knowledge. Let’s dive into why this label doesn’t hold water and how fresh scholarship is changing our view on this pivotal era.

When most people hear “Dark Ages,” they picture a dramatic crash between the fall of the Western Roman Empire in 476 AD and the arrival of the Renaissance. It’s like imagining a dimly lit cave where everyone gropes blindly in ignorance. The truth? It’s far more nuanced—and far more exciting.

Breaking the Myth: What “Dark Ages” Really Implies

Popular culture loves exaggeration. The phrase conjures silly stereotypes: peasants wallowing in mud, kings feasting nonstop, and a Pope burning books just for kicks. This Hollywood-ready image is a caricature that ignores the rich cultural and intellectual activity during the Middle Ages. It’s an easy tale but a bogus one.

Historians today agree that calling these centuries “dark” is _hyperbolic_ and _ludicrous_. Instead of decline, many parts of Europe were busy consolidating power, innovating, and laying groundwork for future achievements. So, why does this myth persist?

The Fall of Rome—A Dramatic End or Continued Story?

The Western Roman Empire ended in 476 AD, but civilization didn’t collapse. Why? Because the other half—the Byzantine Empire—kept going strong for another thousand years. Byzantium wasn’t just “roman leftovers.” It was a Mediterranean superpower and a cradle for science, philosophy, and medicine.

Unfortunately, Western Europe often dismissed Byzantium. There was a long-standing animosity that blurred objective understanding. Thankfully, modern scholars have started giving Byzantium its due credit. That means, the “end of Roman civilization” is more fiction than fact.

Western Europe: Not Just a Recovery Zone

It’s tempting to imagine the West after Rome’s fall as lost and lazy. However, kingdoms like the Merovingians and Lombards emerged, showing political innovation and cultural development. These formations eventually led to the Holy Roman Empire—a major player in medieval Europe.

This period was more about transformation and adaptation than outright decay. Society wasn’t falling apart; it was becoming new, albeit in a different shape than the Roman mold.

The Renaissance: A Light on Long-Simmering Flames

Another common myth is that the Renaissance burst forth suddenly from the bleakness of the Dark Ages. Think of it like fireworks appearing out of nowhere. But the Renaissance was more a flowering of ideas that had been growing quietly since the 10th century.

Byzantine scholars, as well as other cultures, had already developed many fields Renaissance artists and scientists would later celebrate. The “rebirth” was actually a _continuation_ of slow-building progress rather than a dramatic new dawn.

Preservation of Knowledge: Who Really Saved Greco-Roman Texts?

Many credit Muslim scholars alone with safeguarding ancient Greco-Roman learning. While their role was significant, they actually received many texts from Byzantine emperors—such as Theophilos under Caliph al-Mamun’s request.

Byzantine institutions like the Pandidakterion and the Great Library of Constantinople safeguarded over a million volumes for centuries before the tragic Fourth Crusade sack in 1204. Thanks to Byzantine trade networks, Italian maritime states gained early access to many of these works— well before translations from Arabic versions arrived.

Yes, Muslims were vital in understanding and expanding on ancient knowledge, especially in mathematics and science. But giving them sole credit overlooks this rich chain of stewardship and intellectual exchange.

The Problem with the Term “Dark Ages”

Calling an epoch the “Dark Ages” is an oversimplification that erases complexity. It ignores achievements by Byzantium and Western Europeans alike. It paints people as uncultured degenerates who survived on superstition and ignorance. That’s an unfair, even insulting, distortion.

Using the term perpetuates ignorance of over a thousand years of vibrant intellectual and cultural progress. It hampers appreciation for the era’s real contributions, such as the evolution of kingdoms, preservation of texts, and early scientific inquiry.

So, Why Does the Term Persist?

The phrase “Dark Ages” is catchy and easy but outdated. It’s rooted in Renaissance thinkers who framed their own era as a bright “rebirth” against preceding darkness. However, this oversimplified the long, fascinating journey in between.

Modern historians promote a more nuanced view, encouraging curiosity about those centuries instead of relying on stereotypes. After all, calling a thousand years “dark” is lazy thinking—not to mention it overlooks many dazzling sparks.

Final Thoughts: The “Dark Ages” Weren’t Really That Dark

So there it is: the medieval “Dark Ages” is a misnomer that squashes a diverse chapter of human history into a dull, misunderstood label. Europe wasn’t stumbling blindly in dimness; it was walking steadily, learning, building, and exchanging ideas.

Looking beyond this archaic phrase opens up a richer appreciation for all that came before the Renaissance—and for the many cultures, like the Byzantines, who kept the torch of knowledge burning. Next time you hear “Dark Ages,” ask yourself: how dark can a history really be when it brims with kingdoms, libraries, trade, philosophy, and innovation?

History is never as simple as labels suggest. What other misunderstood eras deserve a fresh look?

Why is the term “Dark Ages” considered inaccurate for describing medieval Europe?

The term suggests Europe was backward and uncivilized after Rome fell. It ignores many advances in politics, culture, and technology that occurred during this time.

Did civilization end in Europe after the Western Roman Empire’s fall?

No, the Eastern Roman Empire, or Byzantine Empire, thrived for another thousand years. It made major contributions in science, philosophy, and medicine, maintaining a rich intellectual tradition.

How did the Byzantine Empire influence the preservation of ancient texts?

Byzantines preserved a vast number of Greco-Roman works in their libraries. They later shared many with Muslim scholars, who built on them, and these texts eventually reached Western Europe.

Was the Renaissance a sudden break from the Middle Ages?

The Renaissance built on centuries of development from Byzantine and medieval European efforts. It was a continuation, not a sudden rebirth, with many ideas dating back to earlier times.

Why is the idea that Muslims solely saved Greco-Roman knowledge incorrect?

Muslims played a crucial role in advancing mathematics and science, but much knowledge was preserved earlier by Byzantium. They provided many of the original texts that Muslims translated and studied.