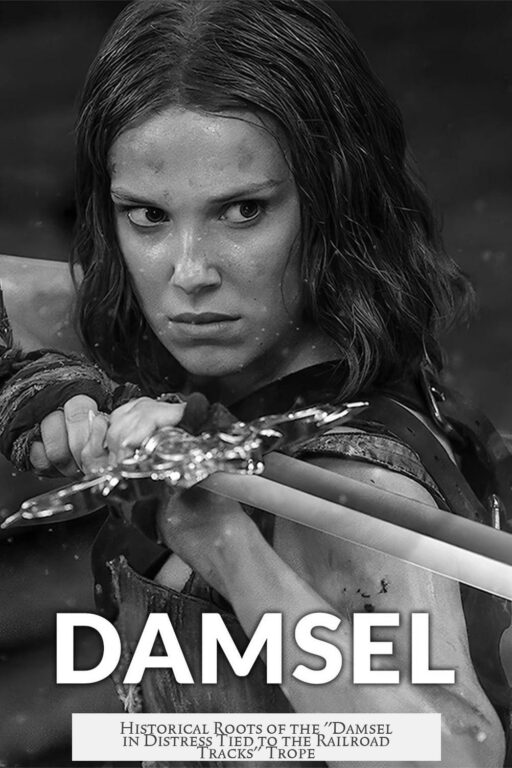

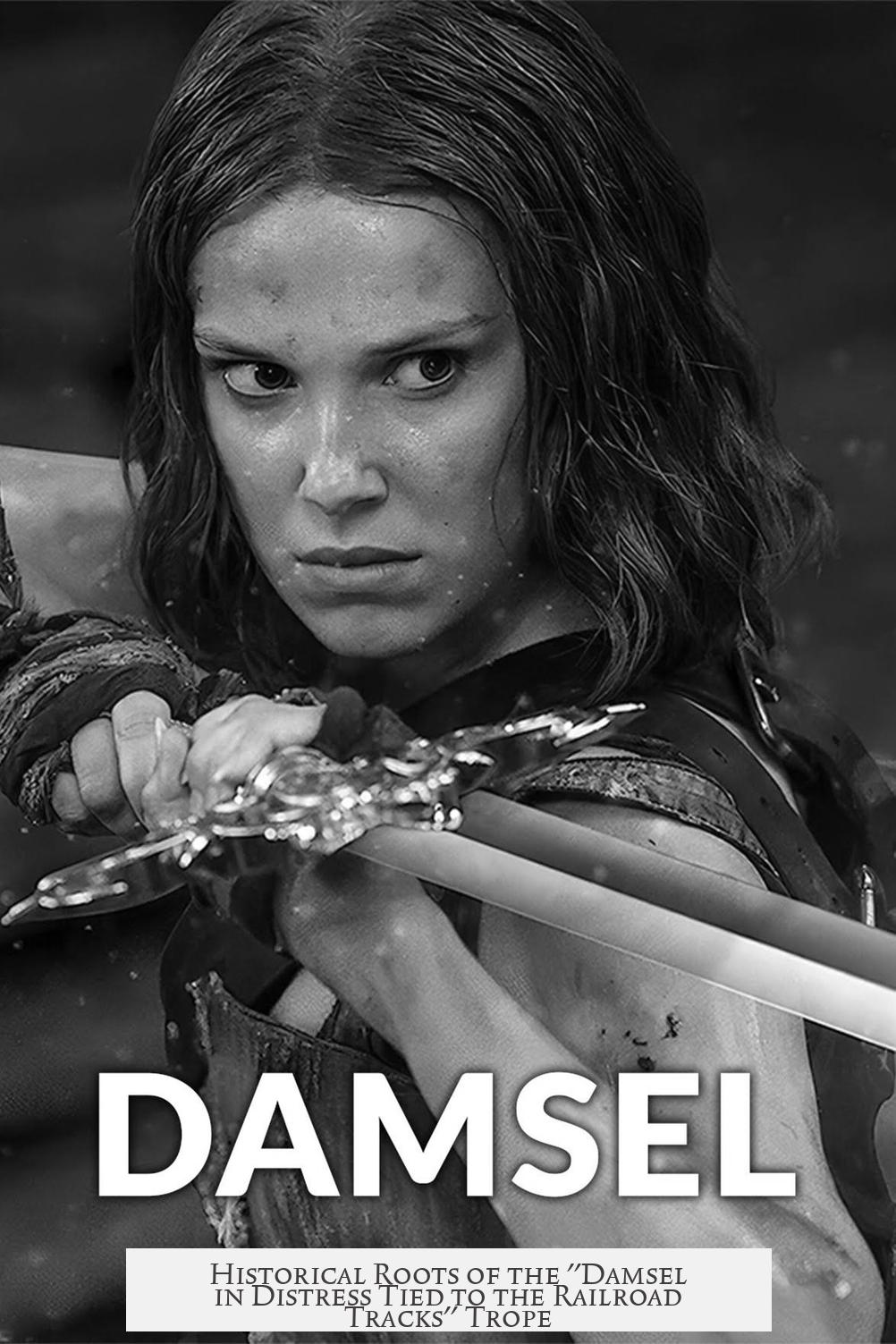

The “Damsel in Distress tied to the Railroad Tracks” trope does not have a solid basis in actual history. It mainly arises from Victorian melodrama and early cinematic comedy rather than real events or common dramatic practice. The familiar image of a woman bound to railroad tracks by a villain is more a product of parody and cultural memory than reality.

The notion that villains frequently tied women to train tracks is a misconception. This scene, now viewed as a classic melodramatic cliché, was rarely depicted in old films and did not occur as commonly as people think. The trope evokes a strong visual but originates more in theatrical and cinematic tradition than history.

The earliest known instance of a character tied to railroad tracks dates to an 1867 Victorian melodrama named Under The Gaslight. However, the person tied on the tracks was a male character named Snorkey, not a woman. He was saved by the play’s leading lady, reversing the familiar gender roles. This origin diverges significantly from the popular image yet established the idea of peril involving trains.

During the silent film era in the early 1900s, many movies borrowed from stage melodramas. Trains, as a major form of transport, commonly featured in films. Characters—often male heroes—ended up on the tracks accidentally or through villainy, sometimes requiring rescue by women. Famous serials like The Perils of Pauline included many dangerous scenarios for the heroine but notably never showed her tied to railroad tracks.

Key elements of the trope, such as the mustachioed villain gleefully binding a helpless woman, are inaccurate. Films of the era avoided such overt melodramatic theatrics. Instead, incidents with trains were often accidental or involved male protagonists. Attempts to prove the trope’s commonality sometimes improperly cite comedies where the trope was parodied, rather than genuine suspenseful dramas.

Notably, the specific scene of a woman tied to train tracks developed mostly through silent film comedies that spoofed earlier melodramas. Films like Barney Oldfield’s Race for a Life and Teddy at the Throttle deliberately exaggerated and mocked these dramatic clichés. These parodies contributed more to the trope’s popularization than any serious dramatic work.

The continued confusion around this trope owes a lot to how these comedic scenes have been more widely accessible and remembered than the original serious plays and films. According to Fritzi Kramer, who has researched this subject, relying on parodies to represent historical drama is like using a modern spoof to claim past trends—an inaccurate leap.

The trope’s endurance grew with later media. When The Perils of Pauline was remade in 1947 with sound, the heroine ended up tied to the tracks, aligning the story closer to the imagined trope. The caricature villain Snidely Whiplash from the Rocky and Bullwinkle cartoon famously employed this method, cementing the image in popular culture as shorthand for villainy.

Today, the scene persists as a symbol of exaggerated villainy and damsel peril. It does not frequently appear in modern films but remains a recognizable motif, often referenced or parodied for its melodramatic flair. Part of the persistence is due to public memory and the gap in historical knowledge about silent film content.

True peril in silent films and melodramas often involved more serious threats such as sexual assault, which received less trivial treatment. Tying a woman to train tracks was considered a less serious or offensive danger in that context. However, many people strongly believe in the trope’s frequent historical occurrence despite scant evidence.

| Aspect | Historical Fact |

|---|---|

| Victorian origin | Character tied to tracks in 1867 play Under The Gaslight, but a man was tied, saved by a woman. |

| Silent film use | Train peril scenes common, but women rarely tied to tracks; male heroes often rescued by women. |

| Comedic portrayals | Women tied to tracks mostly appeared in silent film comedies parodying melodramas. |

| Modern perception | Popularized by remakes and cartoons; a visual shorthand for villainy rather than historical reality. |

- The classic railroad-track damsel scene is a fictional invention from theatrical melodrama and early film parody, not historical fact.

- Early examples reversed modern gender roles, with men tied to tracks and women rescuing them.

- Silent films depicted train dangers but rarely featured the specific “female victim tied to tracks” scenario.

- The trope became solidified by comedic spoofs and later sound film remakes, plus cartoon villains.

- Public belief in frequent historical use persists despite the trope’s rarity in actual dramatic works.

Did actual criminals ever tie women to railroad tracks as a method of attack?

No. Despite what films show, there is no historical evidence that tying women to railroad tracks was a real criminal act. The trope is mostly a creation of melodramatic fiction and later parody.

Where did the railroad tracks peril first appear in drama?

The earliest known example is from an 1867 Victorian play called Under The Gaslight. However, in this case, a man was tied to the tracks and saved by a woman, reversing the modern trope.

Was the “damsel tied to the tracks” scene common in silent films?

No. Silent films often featured train peril, but it rarely involved a woman tied to the tracks by a villain. Men more often found themselves in danger on train tracks and needed saving.

How did the classic damsel tied to railroad tracks trope become popular?

The trope grew from silent film comedies that spoofed earlier melodramas. Films like Barney Oldfield’s Race for a Life parodied the exaggerated peril scenes, cementing the image in popular culture.

Why do many people still believe this trope was historically common?

Misconceptions persist because silent comedies featuring the trope are more accessible today than the serious melodramas they spoofed. This fuels the false idea that the trope was widespread.

What role does this trope play in modern media?

Today, the damsel tied to railroad tracks is mostly a symbol of outdated villainy. It often appears in cartoons and parodies, serving as a visual shorthand rather than a reflection of real history.