In the 1950s, Southern Democrats differed from Republicans primarily in their racial policies, economic priorities, and political goals. Southern Democrats staunchly supported segregation and upheld white supremacy to maintain control in the South. In contrast, many Republicans, especially in the North, opposed such systems and aimed to repeal parts of the New Deal.

Southern Democrats championed the New Deal policies, benefiting Southern agriculture and infrastructure projects like the Tennessee Valley Authority (TVA). This support came despite their conservative stance on race. Conversely, conservative Republicans sought to roll back the New Deal, viewing it as excessive government intervention. Their power base was mainly in the largely white northern states.

The fundamental fear among Southern Democrats centered on federal government interference, but it focused on protecting their racially discriminatory systems rather than opposing economic redistribution. They resisted federal attempts to dismantle their political control, which they viewed as a threat to their dominant social order.

Despite some surface similarities, Southern Democrats and conservative Republicans had little common ground. Their institutions and objectives differed, preventing any real alliance. The Southern Democrats’ main priority was protecting segregation and political dominance, while conservative Republicans prioritized reducing federal economic programs.

Southern Democrats did not immediately shift to the Republican Party in the 1950s or early 1960s, even after Barry Goldwater’s 1964 presidential campaign that opposed civil rights legislation. Only a few Southern politicians switched parties initially. It was only after federal civil rights interventions in the 1960s and 1970s weakened their grip that many Southern Democrats began aligning with the Republican Party.

The Republican Southern Strategy in the 1980s further attracted former Southern Democrats by appealing to racial and cultural sentiments. However, the full realignment of Southern politics extended into the 1990s, particularly with the emergence of the Christian right within the Republican Party.

- Southern Democrats supported segregation and New Deal programs benefiting the South.

- Conservative Republicans opposed the New Deal and had northern power bases.

- Fear of federal intervention was racial, not economic, for Southern Democrats.

- Southern Democrats and Republicans lacked shared goals, delaying political realignment.

- The Republican Southern Strategy attracted former Southern Democrats by the 1980s.

In the 50s, How Were the Southern Democrats Actually Different from Republicans?

If you’re wondering how Southern Democrats in the 1950s differed from Republicans, the main difference boils down to something quite stark: racism. Yes, you read that right. The split isn’t just about policies or party labels—it’s about race and control.

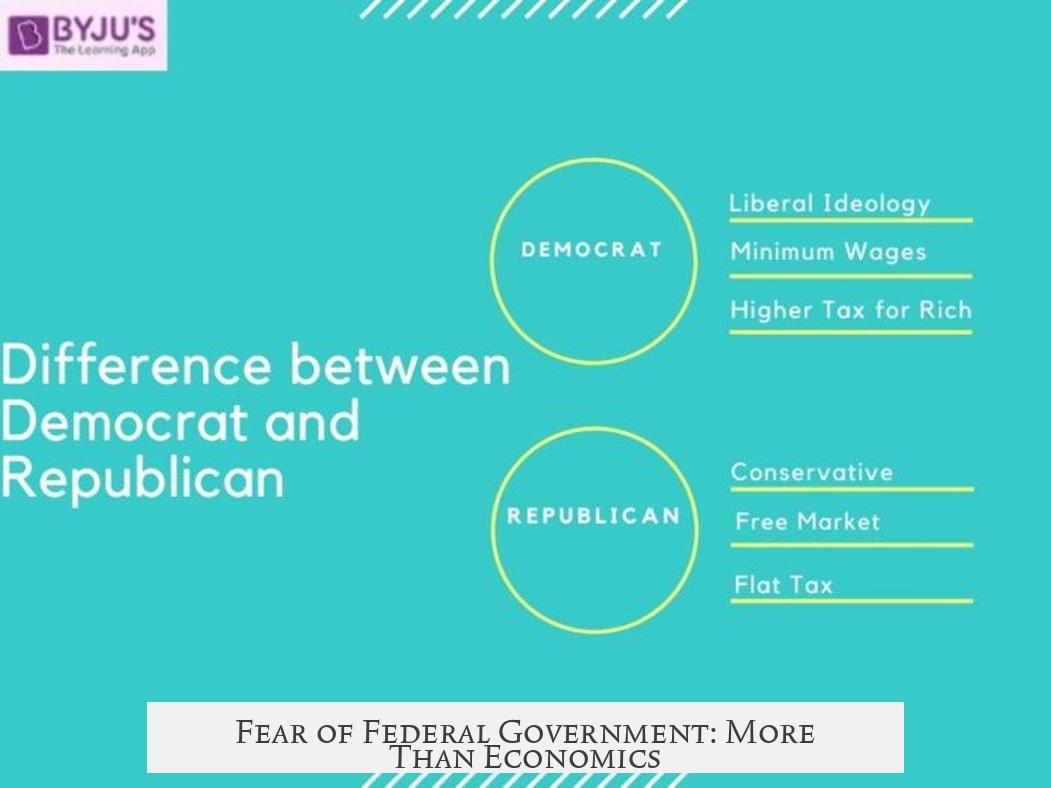

The 1950s was the era of the Jim Crow South, where Southern Democrats held tight to white supremacy, using every political tool to maintain racial segregation and disenfranchisement. Meanwhile, conservative Republicans, mostly hailing from the North, had different priorities. They frequently opposed some New Deal programs and were less invested in maintaining racist state structures. Understanding these nuances explains why it’s misleading to paint the era’s party conflicts as simple “Democrats vs. Republicans.”

The Racism Fault Line: Southern Democrats vs. Conservative Republicans

Southern Democrats’ politics pivoted on the fear of a federal government that might interfere with their racial order. In contrast, conservative Republicans—largely situated in the North—focused on repealing New Deal legislation and limiting government expansion.

So, while conservative Republicans opposed big government economically, Southern Democrats feared federal intervention because it threatened white control within their region. They defended the status quo through racist laws and graft, not so much battered by economic policies but by potential integration and black empowerment.

Does that sound like a cooperation of equals or more like uneasy neighbors sharing the same street but vastly different worldviews and goals? You bet on the latter.

Economic Policy: New Deal and Agricultural Support

The New Deal adds a nice wrinkle in the story. While many Republicans sought to dismantle President Franklin D. Roosevelt’s New Deal programs, Southern Democrats largely supported them. Why? Programs like the Tennessee Valley Authority (TVA) and other agricultural initiatives helped rural Southern economies, where poverty and farming dominated.

- Republicans’ View: Saw the New Deal as government overreach, wasteful spending, and threats to free enterprise.

- Southern Democrats’ View: Embraced New Deal policies because they brought federal dollars, jobs, and infrastructure to their states.

This support didn’t mean Southern Democrats were progressive on racial issues; rather, economic self-interest overrode any ideological alignment with Republicans on economic conservatism. They wanted the economic benefits but without federal tampering in social issues, especially race.

Fear of Federal Government: More Than Economics

Southern Democrats’ conservatism stems from more than economics. Their primary concern was governing a corrupt, racist system that ensured white dominance throughout the South.

Federal government interference posed a direct threat to this order. The threat wasn’t only about redistributing wealth or economic regulation; it was about breaking apart the political and social system Southern Democrats had entrenched for decades.

“They feared the federal government less on the basis of economic redistribution, and more because they fear that very same federal government will be used to break apart their corrupt, racist political system.”

So, the South’s Democrats saw federal involvement as an enemy not because it expanded the New Deal but because it chipped away at Jim Crow.

Institutional Barriers and Lack of Common Ground

These two groups—Southern Democrats and conservative Republicans—have so little in common that they hardly align on much except a surface-level conservatism. Institutional and political barriers prevent any real coalition.

On one hand, Republicans opposed big government economically; on the other, Southern Democrats accepted government aid while fiercely guarding their region’s racial order. They nominated candidates, enacted laws, and operated systems incompatible with forming a united front.

The Slow Southern Democrats’ Shift Toward Republicans

Not until the mid-1960s do things get really interesting. Southern Democrats didn’t immediately jump ship after Barry Goldwater’s 1964 campaign, who opposed the Civil Rights Act. Only rare exceptions like Strom Thurmond switched early.

It took the federal government’s civil rights interventions in the 1960s and 70s—breaking Southern political machines and opening voting rights—that shook the foundation. Forced to adapt, white Southern conservatives found a new home in the GOP, amplified by the Republican “Southern Strategy.” This strategy used coded racial appeals to attract these voters.

By the 1980s, the slowly blooming alliance between these conservatives and Republicans started bearing fruit electorally. Southern politics shifted, but the process was gradual, uncomfortable, and marked with tension.

The Enduring Legacy

Interestingly, one could argue the legacy of the Southern Democrats as a political force truly ended much later—around the 1990s—which is when the Republican Party was firmly captured by the Christian right. That alliance cemented new social and political priorities on the right, differing even further from the old Southern Democratic traditions.

Wrapping It Up: A Complex Political Landscape

The tale of Southern Democrats versus Republicans in the 1950s is a story of competing priorities, racial control, and strategic political moves. It is not a simple tale of party lines but a reflection of history and power dynamics.

So next time you hear about the parties of the ‘50s, remember: Southern Democrats clung to Jim Crow and New Deal economic benefits alike, while Republican conservatives opposed New Deal expansion and, at least in the North, didn’t share the South’s racial agenda—yet.

Curious how these historical dynamics still echo in today’s political landscape? It’s a fascinating question—and one worth exploring in its own right.