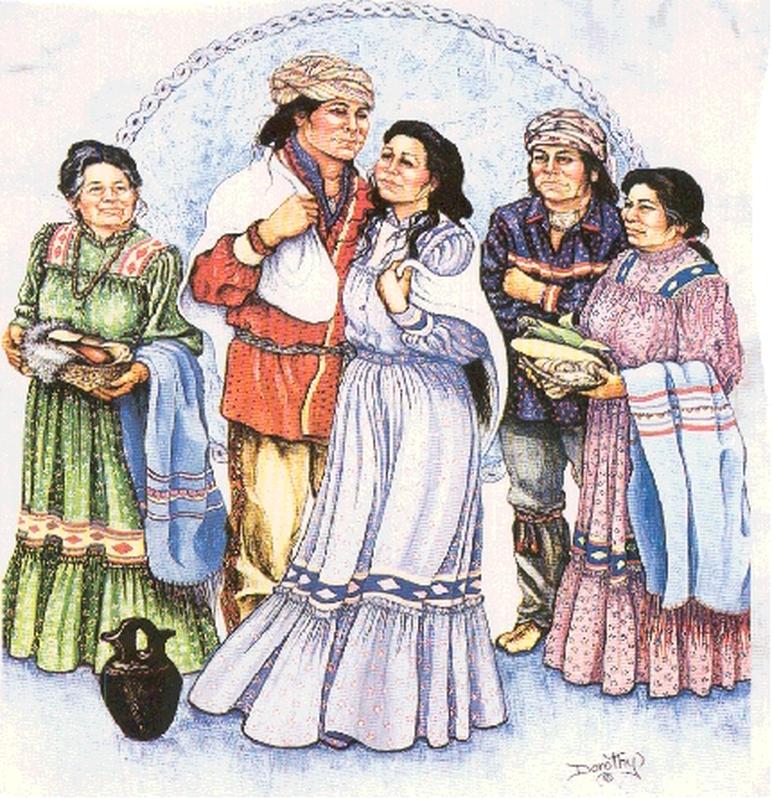

Sex and dating in Native American societies such as the Cherokee featured distinctive cultural norms marked by sexual freedom, clan-based restrictions, and negotiated marriage arrangements.

The Cherokee practiced particular sexual restrictions tied to the spiritual significance of blood and life energy. Pregnant women, menstruating women, and warriors preparing for hunts or battles refrained from sexual activity. These rules were rooted in the belief that blood embodied life and spirit, warranting careful conduct during sensitive periods.

Women in Cherokee society enjoyed considerable personal autonomy in sexual matters. They were free to choose their partners, provided relationships did not violate incest taboos—which were rigorous due to their matrilineal clan system. Punishments for adultery were nonexistent for women, and men often regarded disputes over adulterous women as beneath them.

Sexual encounters took place in private but natural settings, often in beanfields, corn cribs, and similar secluded areas. Such locations favored discretion amid loose societal restraints.

Marriage frequently involved formal courtship and arranged negotiations. According to ethnographic sources, a young man initiated interest by sending his mother’s sister to propose through the young woman’s maternal kin. The matrilineage held significant power in accepting or rejecting the proposal, though the bride’s consent was ultimately mandatory.

Proposals involved symbolic gift-giving; a suitor presented a freshly killed deer to the woman’s family. Acceptance was signaled by the woman preparing and sharing the deer meat with him, while refusal equated to rejecting the suitor.

The Cherokee permitted polygyny, contingent on the permission of the first wife. Both spouses could initiate divorce, reflecting flexible marital norms uncommon in many contemporary societies.

In terms of sexual freedom, Cherokee culture was notable. Both men and women could have multiple lovers, though women could not marry multiple men or keep concubines. Cheating was frowned upon by neighboring groups but more tolerated among the Cherokee.

The Cherokee’s matrilineal social structure shaped sexual and marital customs profoundly. Children belonged to the mother’s clan, not the father’s. Kinship emphasized the mother’s brother as the primary male relative, not the biological father. Incest prohibitions extended across both maternal and paternal clans, preventing marriage within those boundaries.

| Clan Names | Purpose in Marriage |

|---|---|

| Wild Potato, Long Hair, Deer, Blue, Wolf, Bird, Paint | Defined permissible marriage choices; avoided incest by selecting spouses from other clans. |

Comparatively, other Native American groups such as the Iroquoian peoples (Wendat/Huron, Haudenosaunee) practiced courtship with considerable sexual liberty beginning at puberty. Young men and women courted freely but marriage arrangements were overseen by Clan Mothers. Trial marriages allowed couples to test compatibility before commitment.

Clan Mothers held authoritative roles in marriage, negotiating unions, enforcing marital harmony, and adjudicating divorces, which either spouse could request. Extramarital affairs were accepted; men might have “Hunting Wives,” and women could have multiple husbands in certain cases.

Among Algonquian groups, courtship included formal gift-giving to parents, public courting signals like flute playing, and subtle marriage acceptance rituals such as the “blanket ceremony.” Marriages often lacked formal ceremonies, with couples spending time alone to mark union.

European contact introduced new dynamics. European men sometimes intermarried with Native women or engaged in brief relationships to establish trade ties. Despite this, cultural double standards existed. Europeans often accepted these alliances but resisted similar arrangements for their women or Native male partners.

Overall, Native American societies like the Cherokee embraced nuanced attitudes regarding sex and dating. Their systems balanced sexual freedom with clan-based restrictions, valued female choice, and incorporated complex kinship rules to avoid incest and define family structure.

- Sexual activity was restricted during pregnancy, menstruation, and warrior preparation due to spiritual beliefs about blood.

- Women had sexual autonomy and were free to select partners barring incest prohibitions.

- Marriage arrangements involved maternal kin, with gift-giving proposals and mandatory female consent.

- Polygyny was practiced but required the first wife’s approval; divorce was available to both spouses.

- The Cherokee matrilineal clan system dictated kinship, marriage choices, and incest prohibitions.

- Other tribes, like the Iroquois, allowed trial marriages and sexual freedom under clan mother oversight.

- European interactions introduced new social complexities and double standards related to intermarriage.

What Were Sex and Dating Like in Native American Societies Such as the Cherokee?

When it comes to the intimate lives of Native American societies like the Cherokee, the picture is far richer and more complex than we often imagine. Sex and dating were not only matters of personal connection but deeply bound to spiritual beliefs, clan ties, and social customs. In short, they were unique, respecting both individual freedom and community harmony.

Let’s dive into how the Cherokee—and their neighbors—approached these topics with a fascinating mix of tradition, freedom, and rules.

The Spiritual Rules of Sex and Bodily Autonomy

First off, the Cherokee tied sexual conduct closely to the powerful symbolism of blood, which they considered the very essence of life and spirit. Pregnant women, menstruating women, and warriors preparing for hunts or battles were strictly prohibited from engaging in sex. This wasn’t some puritanical rule; it was about respecting and preserving vital spiritual energy. For them, blood wasn’t just blood—it was life force that shaped the community’s health.

Interestingly, Cherokee women enjoyed personal autonomy comparable to that of modern U.S. women concerning sexual partners. They could choose whom to engage with freely, provided it wasn’t within prohibited family lines. Imagine dating apps before apps, with the clan acting as the matchmakers ensuring no incestuous entanglements.

Another fascinating fact: adultery wasn’t punished. Many Cherokee men felt below themselves to fixate on it or quarrel over it. This was a tacit cultural acceptance of female promiscuity. If anything, the Cherokee respected a woman’s choice to have lovers outside marriage, though marriage itself remained an exclusive bond.

Some Wild Locations for Romance

Sexual encounters didn’t always take place in bedrooms. The bean fields, corn cribs, and patches were popular secret spots. This gave new meaning to “fieldwork.” Privacy in nature was common. Such places offered intimacy while connecting with the cycles of agricultural life, reinforcing their bond with the earth.

Marriage and Courtship: When Tradition Meets Consent

Despite the personal freedoms, marital unions reflected communal values. A young man initiated marriage talks by sending his mother’s sister—emissaries in Cherokee matchmaking tradition—to speak to the young woman’s mother’s sister and her matrilineage. Consent of the woman was absolutely required. She had the final say. If the clan approved, word extended back to the man’s clan, completing this inter-family communication loop.

Gifts mattered. The suitor would kill a deer and present the meat to the girl’s family. If she accepted by cooking and sharing the meat with him, that meant yes to marriage. Rejecting the deer meat? That was a polite but clear “no.” Gift-giving and acceptance served as their own engagement ceremony without pom-poms or Instagram posts.

Polygyny and Divorce: Flexibility in Relationships

Polygyny was accepted but regulated. The first wife’s permission was necessary before a man could take another wife. Divorce also existed and could be initiated by either spouse—demonstrating a far more flexible system than rigid marriage laws most of us know today.

Clan System and Incest: The Matrilineal DNA of Relationships

The Cherokee were matrilineal. Children belonged to their mother’s clan, not their father’s. This flips Western ideas on their head. Your mother’s brother (your uncle) was more like your father figure than your biological dad. This matrilineal focus also affected dating and marriage rules profoundly.

Incest was forbidden not just within your mother’s clan, but also anyone linked to your biological father’s clan—a two-front rule to safeguard social order and genetics.

The Cherokee had seven clans: Wild Potato, Long Hair, Deer, Blue, Wolf, Bird, and Paint. Each village had representation from all clans, so people had a range of potential partners—usually from five other clans—avoiding close kinship and bolstering community ties.

Iroquoian Neighbors: Courtship and Marital Practices

Neighboring societies like the Wendat/Huron and Haudenosaunee/Iroquois had some similarities, but also unique twists. Boys and girls entered puberty with considerable sexual freedom, often courting multiple suitors. This made the early French missionaries protest loudly over the “loose morals,” but really, it was all about clan lines and personal choice.

As young adults approached marriageable age, Clan Mothers negotiated unions. The woman chose her suitor from among multiple options. When she nominated a man, a trial marriage period began. The man lived mostly in the woman’s longhouse, and her Clan Mothers observed their interactions carefully. If the Clan Mothers disapproved, the man and his gifts returned home.

If the match passed these tests, a feast marked the official marriage, and the man stayed under his wife’s clan’s authority. Clan Mothers settled disputes, including forcing divorces when necessary due to reasons such as infertility or violence.

One excellent twist: marriage was primarily about children, not sexual fidelity. Men and women could have extramarital relationships without stigma. Men had “hunting wives,” women who went out with hunting parties and didn’t follow traditional domestic roles. Among the Seneca, some women even practiced polyandry well into the 20th century.

Algonquian Courtship: The Art of Flirting and Gift Giving

Further east, Algonquian tribes practiced mostly monogamous marriages, but polygyny was allowed for important men. Courting had a communal element: the suitor spoke to the girl in the middle of her lodge with adults nearby—no secret rendezvous!

“Courting flutes” were a popular romantic tool, though the girl couldn’t leave her lodge when one was played—talk about some strict concert rules! As the man became serious, he offered a deer to her parents, proving he could provide. If invited to share the meal, he gained implicit parental approval.

The Potawatomi youth had a charming tradition: offering a blanket to a girl at courtship. If she allowed him to put it over her shoulders, it meant marriage acceptance. No big church ceremony followed; the couple simply left for a few days together to start life as partners.

The European Impact: Intermarriage and Unequal Expectations

When Europeans arrived, they often sought to intermarry with Native women or engage in brief liaisons to gain trading advantages. However, Native women were sometimes treated badly in these encounters—a sad reality amid cultural exchanges.

More hypocritically, Europeans demanded sexual access to American Indian women but denied the same for Native men with European women or even via intermarriage. This double standard clashed with the Native traditions of sexual freedom and mutual respect.

Lessons from Native Societies About Sexual Freedom and Relationships

These Native American systems, especially among the Cherokee and their neighbors, offer insightful lessons today:

- Sexual Autonomy with Boundaries: Freedom was valued, but spiritual laws respected bodily cycles and community rituals.

- Female Empowerment: Women chose partners freely, had the power to consent to or reject marriage, and could maintain extramarital relationships without fear.

- Community Oversight: Marriages involved families, clans, and elders, providing a support system and conflict resolution mechanisms.

- Flexible Marital Arrangements: Polygyny was allowed but regulated, and divorce was accessible, highlighting adaptability.

- Matriarchal Kinship: Prioritizing the mother’s clan deepened women’s social importance and created unique familial roles.

Native Americans balanced sexuality, love, family, and spirituality deftly. Their customs challenge Western ideas of monogamy, fidelity, and gender norms and demonstrate that human relationships can thrive under diverse systems.

What Can We Take Away?

Reflect on this: cervical cycles, warrior rituals, and clan ties shaped when and how intimacy happened. Women held surprising autonomy, sometimes even honor, in expressions of desire. Marriages weren’t just about two people—they were bonds between families, clans, and spirits.

In an era where dating apps and hookup culture often ignore deeper connections, exploring these traditions reminds us about respect, consent, and community value—a lesson worth remembering.

“The Cherokee honored both the life spirit in their blood and the freedom of the individual heart.”

Wouldn’t it be refreshing to bring a little of that balance into today’s tangled world of dating?