Juana I de Castilla, nicknamed “la Loca”, was not the victim of a widespread propaganda campaign designed specifically to discredit future female rulers. Instead, her discrediting arose from a complex mix of personal, political, and familial factors unique to her circumstances. Misogyny and power struggles did contribute to the portrayal of Juana as mentally unstable, but historians find no solid evidence of an organized effort aimed at preventing women from ruling in Spain more broadly.

Juana’s reputation for madness largely stems from the actions of powerful men, especially her father, Fernando II of Aragon. After Queen Isabel I died, Juana inherited the throne of Castile as per Isabel’s will. However, the will allowed Fernando to serve as regent if Juana was judged unfit or unwilling to rule. Fernando seized this opportunity to claim power, portraying Juana as mentally unbalanced to justify his regency.

This portrayal was politically convenient. Juana exercised power briefly and often opposed her father’s control, which Fernando depicted as irrational hysteria. His narrative framed himself as a caretaker with experience stepping in to “help” a troubled queen. Over time, Juana’s imprisonment and loss of power likely led to depression, reinforcing the perception of instability. Her son, Carlos I, later used this to continue her confinement.

Historians emphasize that this campaign against Juana’s agency was rooted in her specific life context. It involved her strained marriage, the power dynamics of her parents’ co-rulership, and the death of her husband. These personal and political conflicts created a situation ripe for her exclusion rather than reflecting a grand design to block female sovereignty entirely.

Importantly, during the Early Modern period, women ruling was not fundamentally opposed in principle. Isabel I’s own accession demonstrates there was acceptance when a woman was clearly the true heir. Succession laws favored male heirs, yet female monarchs were accepted if no legitimate male successor existed. There was little documented anxiety about female rulers in general.

If a broader, systematic attempt to prevent female rule had existed, more overt legislative actions would be expected. For example, France enacted explicit laws to bar women from inheriting thrones. No such broad legal measures appeared in Spain during or after Juana’s lifetime. The denial of Juana’s sovereignty appears to have been an exceptional case, linked to the interests of specific individuals rather than a societal campaign.

Arguments about misogyny are not dismissed. Misogynistic attitudes likely aided political rivals in undermining Juana. The portrayal of her madness drew on common stereotypes to justify power grabs. Yet, historians caution against conflating misogynistic rhetoric with a deliberate propaganda strategy aiming to discredit all future female rulers.

Some popular theories suggest that Juana’s diminished reputation served to deter other women from aspiring to rule. These theories remain speculative and lack strong historical backing. Juana herself remains understudied, and evidence for such an overarching propaganda campaign is meager. References to misogyny as a political weapon generally relate to specific contexts, such as using anti-Catholic polemics in the works of John Knox, rather than to Spanish royal succession.

- Juana’s discrediting resulted from unique, personal and political factors, not a broad propaganda campaign.

- Fernando II leveraged claims of her madness to control Castile, advancing family power.

- Widespread opposition to female rulers did not exist; legal frameworks allowed women to inherit if no male heir was present.

- No historical evidence supports a coordinated effort to prevent future female monarchs specifically.

- Misogyny played a role but served immediate political ends rather than a general anti-female rule agenda.

The case of Juana I de Castilla demonstrates how power dynamics and familial conflicts shaped history. Her story does not prove a conspiracy against female sovereignty but highlights the complexity of ruling in a male-dominated political environment.

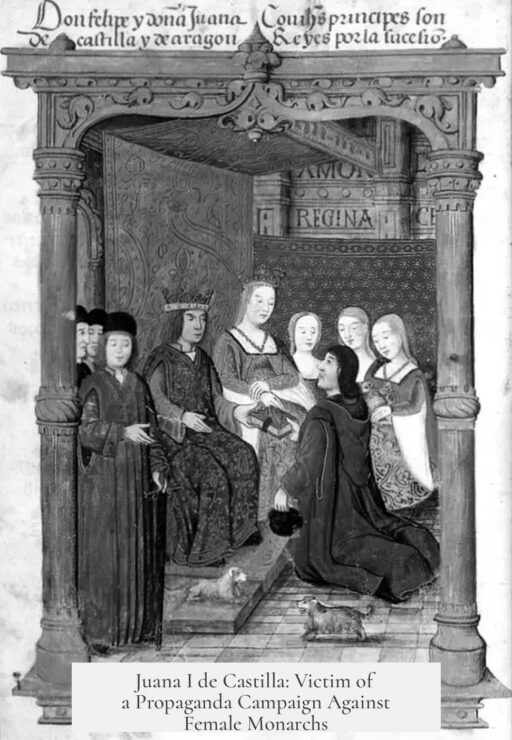

Was Juana I de Castilla, “la Loca,” the Victim of a Propaganda Campaign to Discredit Future Female Rulers?

Short answer: Juana I de Castilla, famously known as “la Loca,” was indeed discredited during her time, but the idea that this was part of a grand propaganda scheme designed solely to prevent future women from ruling Spain lacks solid historical proof. Instead, her downfall was tangled in a web of family politics, personal tragedies, and very human power struggles.

Let’s unravel this fascinating historical drama and see why Juana’s legacy is far more complex than the label “the Mad” suggests. Along the way, we’ll explore if her reputation was weaponized to quash female rule in Spain once and for all.

The Woman Behind the Madness

Juana I de Castilla was a princess turned queen, a woman caught between dynasties and loyalties. Born to the powerful Catholic Monarchs, Fernando and Isabel, she married Philip of Flanders in 1496—a union masterminded to bind the Spanish Trastamara lineage with the Austrian Habsburgs.

This marriage was no fairy-tale romance. Instead, it pushed Juana into a pivotal political role, especially when she became heir presumptive to the unified Spanish kingdoms in 1500.

She was far from powerless—initially at least. Juana gave birth to six children, including future rulers like Charles (later Emperor Charles V) and Catherine, whose story would intertwine with Europe’s royal dramas. Her role was to be a bridge between families and kingdoms, yet her personal agency gets lost—or deliberately obscured—in historical retellings.

Political Intrigue and Family Drama

Once her mother Isabel died, Juana inherited the Castilian throne. However, this inheritance wasn’t a smooth handover but a powder keg of tension. Her father, Fernando, essentially snatched control by declaring himself regent on the excuse that Juana was mentally unstable—a move that conveniently sidelined her and secured his grip on power.

Meanwhile, her husband, Philip, played his own game. He treated Juana like chess pieces treat pawns—separating her from her children, intercepting messages intended for her, and manipulating loyalties. This fractured her family ties and weakened her claim.

What happened next looks like a dark comedy of errors: Juana was caught in a tug-of-war between two powerful men, each claiming to protect her—or perhaps protect their own interests—in the name of her supposed “madness.”

A Tradition of Female Rule—With a Catch

In Iberian history, women had often acted as regents or partners in rule. Isabel of Castile herself was queen by a radical play of politics, managing her kingship with charisma and cunning rather than sheer birthright.

However, when it came to actual reigning queens, traditional norms required that a husband share or even hold the real power. Philip viewed the kingship as something he should wield by right of marriage, while Fernando saw himself as the natural and stronger ruler post-Isabel.

These competing views added to Juana’s troubled reign. Her supposed mental instability became the convenient excuse for sidelining her and maintaining male dominance—a sort of proto-political “alternative facts” in action.

The Myth of Madness: Was Juana Really Crazy?

The idea that Juana was insane has long pedigree. But this “madness” narrative largely came from those who benefited from undermining her. Fernando, especially, amplified rumors about her mental state to justify his regency.

Historians suggest that after years of being imprisoned and cut off from power, Juana likely developed depression and emotional trauma—hardly surprising given the stress and isolation. But she was no raving lunatic running through palaces screaming at shadows.

The long-standing explanation that male guardians stepped in to “save” a helpless woman conveniently masks the very real political ambitions they harbored. This was power dressed up as benevolence.

Was There a Grand Conspiracy Against Female Rulers?

Here’s where history gets really juicy. Some modern narratives suggest Juana’s discrediting was part of a larger plot to prevent women from ruling in the future. It’s a compelling angle—like a medieval soap opera about gender politics.

But the evidence doesn’t quite back this up.

- Juana’s story is unique, shaped by her personal circumstances—contentious marriage, the co-rulership model of her parents, her husband’s death, and her father’s ambitions.

- There’s no substantial proof of a widespread plan to ban women from the throne. If men wanted to block female rulers outright, they could have passed laws—like France did—that barred women from succession.

- Interestingly, people of that era were generally pragmatic. Female rulers were accepted if they had the strongest claim. Isabel’s reign is a prime example.

The claim that Juana’s downfall was a deliberate propaganda campaign to discredit all future female rulers is more myth than documented fact. It was personal, political, and complicated—not a gendered master plan.

Societal Attitudes Toward Women in Power

Contrary to modern assumptions, early modern Europe wasn’t universally hostile to female sovereignty. They did, however, prioritize “the rightful heir” over the generic rule of women. Isabel wasn’t queen because she was a woman but because her competitor was deemed illegitimate.

Male heirs usually took precedence, so female rulers arose mainly in the absence of males. Spain’s history included many women serving as regents or rulers, albeit within patriarchal frameworks.

The notorious pamphlet The First Blast of the Trumpet Against the Monstrous Regiment of Women (1558) by John Knox often gets cited as hardline misogyny. But in context, it was a political jab aimed at Catholic women rulers like Mary I of England. This underlines how gender objections were often weaponized politically rather than based on principle.

Juana’s Later Life: A Queen In Twilight

After her husband Philip’s death in 1506, Juana returned permanently to Spain but was effectively imprisoned in Tordesillas for decades. Her son Charles grew into a powerful monarch, sidelining her authority while showing respect and affection in complicated ways.

Charles once abducted his sister Catherine from Juana’s care to negotiate alliances but returned her after his mother protested through silence—a poignant reminder of Juana’s continued agency despite her captivity.

The loss of her daughter Catherine to marriage and exile worsened Juana’s mental state. Her daughters Eleanor and Isabella joined Charles’s court rather than their mother’s, highlighting Juana’s isolation.

What Can We Learn From Juana’s Story?

Juana’s life isn’t just a cautionary tale of madness or gender politics. It’s a story about power, family, and identity playing out on the grand stage of European politics.

Could Juana have been more than “la Loca” if circumstances were different? Absolutely. Her “madness” must be seen with skepticism, as a tool used by men whose grip on power depended on sidelining her.

For future female rulers, Juana’s story holds lessons. The barriers weren’t about gender alone but about the complex mixtures of ambition, inheritance laws, and societal structures of the time.

Final Thoughts

“Juana was a victim of a conspiracy—but it was a web woven from personal and political strands, not a grand plan to crush women’s power.”

History often simplifies figures into legends—crazy queen, villainous king, innocent victim. Juana is no exception. She was a queen caught in the crossfires of dynastic ambition, family strife, and societal norms that didn’t quite know what to do with a woman who refused to fit the script.

The verdict? Juana I de Castilla was discredited by those around her, but not specifically to discredit all future female rulers. Her story reflects the messy realities of power and perception rather than a clear-cut narrative of misogynistic propaganda.

Does this change how we see women’s roles in history? Definitely. It reminds us to question easy narratives and appreciate the nuanced realities behind history’s most enduring legends.

Was Juana I de Castilla intentionally discredited to prevent future female rulers?

The campaign against Juana focused on her specific situation, not on stopping all women rulers. Men close to her used claims of madness to take power, but no broad effort aimed to block female leadership in Spain is evident.

Did misogyny play a role in portraying Juana as “la Loca”?

Yes. Misogyny helped support the narrative of Juana’s mental instability. Her father and others used this to justify controlling her, but it came from personal power struggles rather than a general attack on women rulers.

Was there any legal action to prevent women from ruling after Juana?

No clear laws or policies were made to bar women from thrones after her. Other countries like France enacted such rules, but in Spain, no wide legislative ban against female succession followed Juana’s case.

Did early modern society oppose female rulers as a rule?

Not necessarily. Many accepted female rulers if they were the rightful heirs. Preference was given to male children, but female rule itself wasn’t broadly rejected. Concerns focused more on legitimate succession.

Is the idea of a propaganda campaign against female rulers in Juana’s case historically supported?

Historical evidence supports a conspiracy against Juana’s agency, not an extensive campaign against all female rulers. The attacks reflected personal and political conflicts without broader intent to discredit women ruling in Spain.