Pro-Confederate defenders respond to the explicit protection of slavery in the Confederate Constitution by emphasizing several key points. They often separate the motivations of average Confederate soldiers from the Confederacy’s government goals, portray the conflict as driven by broader political and economic concerns rather than slavery alone, and rely heavily on the Lost Cause narrative. These defenses attempt to soften or redirect the undeniable fact that slavery was central to the Confederacy’s founding and constitution.

Confederate supporters frequently invoke the Lost Cause ideology. This set of beliefs emerged after the Civil War and seeks to reshape the conflict’s causes. It presents the Confederacy’s motives in a sympathetic light, often downplaying or denying slavery’s central role. The Lost Cause narrative uses selective facts, logical fallacies, and misinterpretations to recast the Confederacy as mainly fighting for states’ rights, homeland defense, or economic independence rather than slavery.

A typical defense is the argument that most Confederate soldiers did not own slaves and fought primarily to defend their homes, family, or state loyalty instead of slavery. Approximately 90% of Confederate soldiers never owned slaves. Proponents claim the “common man” was motivated by local defense, not slaveholding interests. However, the distinction is made between these individual motivations and the Confederate government’s explicit intentions. The Confederate Constitution clearly enshrined slavery as a protected institution, indicating the official purpose was to preserve and perpetuate slavery.

Another defense highlights Northern motives, asserting that the Union’s primary goal was preserving political and economic control rather than abolishing slavery out of moral conviction. Supporters cite Abraham Lincoln’s 1862 letter to Horace Greeley, where he states his “paramount object” was to save the Union, not to save or destroy slavery. Pro-Confederate arguments use this letter to suggest abolitionism was a secondary or insincere goal of the North.

However, this defense faces strong rebuttal. Lincoln’s personal anti-slavery views, the efforts of thousands of Northern abolitionists, and the sustained political activism for abolition reflect a genuine commitment to ending slavery, not merely political maneuvering. Lincoln’s leadership balanced complex duties but did not erase the moral and social forces pressing for emancipation. The abolitionist cause operated independently and often at great personal cost to its followers in the North.

Pro-Confederate defenders also emphasize Southern fears related to the expansion of slavery. Many white Southerners believed slavery required ongoing territorial growth to survive economically and socially, a belief rooted partly in historical events like the Haitian Revolution. The fear was that restricting slavery’s expansion into new territories would eventually doom it in the South. The 1857 Dred Scott decision, which declared Congress could not prohibit slavery in the territories, was seen as a last political victory. When that control seemed threatened, secession appeared necessary to ensure slavery’s survival.

These arguments, however, do not change that the Confederate government founded itself explicitly on protecting slavery. The Confederate Constitution stated that the institution was a “domestic institution” protected from any federal interference. The government seceded to preserve slavery as the cornerstone of Southern society and economy. The gap between government purpose and soldier motivation does not erase the Confederacy’s stated goal.

| Pro-Confederate Defense | Counterpoints |

|---|---|

| Most soldiers fought for homeland defense, not slavery. | Government documents explicitly prioritized slavery protection. |

| The North fought for political and economic reasons, not abolition. | Abolitionist activism was real, widespread, and morally driven. |

| Lincoln prioritized saving the Union over slavery abolition. | Lincoln’s personal anti-slavery stance and abolitionist pressure were strong. |

| Southern fears focused on slavery’s expansion, not immediate abolition. | Expansion fears reflect the centrality of slavery to Confederate ideology. |

In brief, pro-Confederate defenses against the explicit protection of slavery rely heavily on separating individual motivations from government intent, casting Northern motives as self-interested, and emphasizing fears about territorial slavery expansion. The Lost Cause narrative strongly influences these defenses by attempting to recast the Confederacy’s purpose. Yet historical evidence shows the Confederate government explicitly protected slavery in its constitution, making this fact central and non-negotiable in understanding the Confederacy’s aims.

- The Confederate Constitution explicitly protected slavery as a core institution.

- Most Confederate soldiers may not have owned slaves but fought primarily for local defense.

- Northern motives combined Union preservation with abolitionist activism.

- Lincoln balanced political strategy with personal anti-slavery convictions.

- The Lost Cause narrative distorts Confederate motives to minimize slavery’s role.

If Slavery Was Explicitly Protected Within the Confederate Constitution, What Defense Do Pro-Confederate People Have Against That?

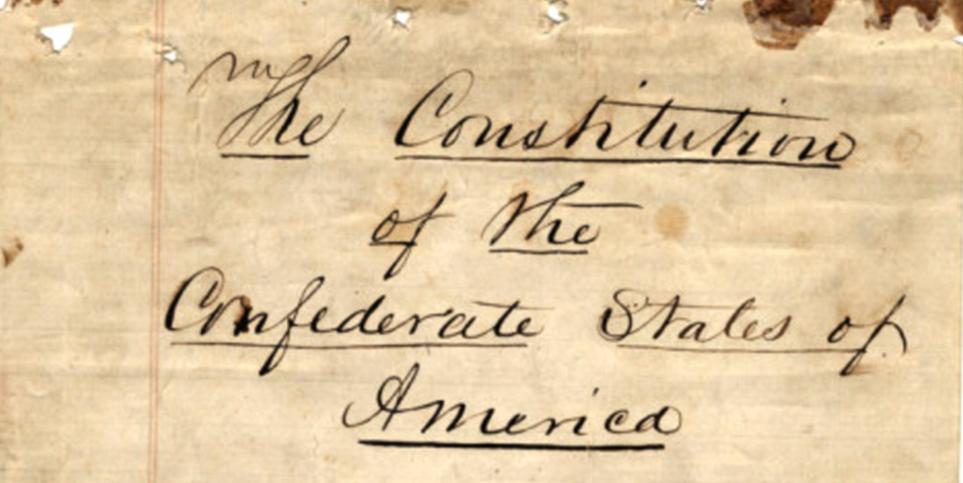

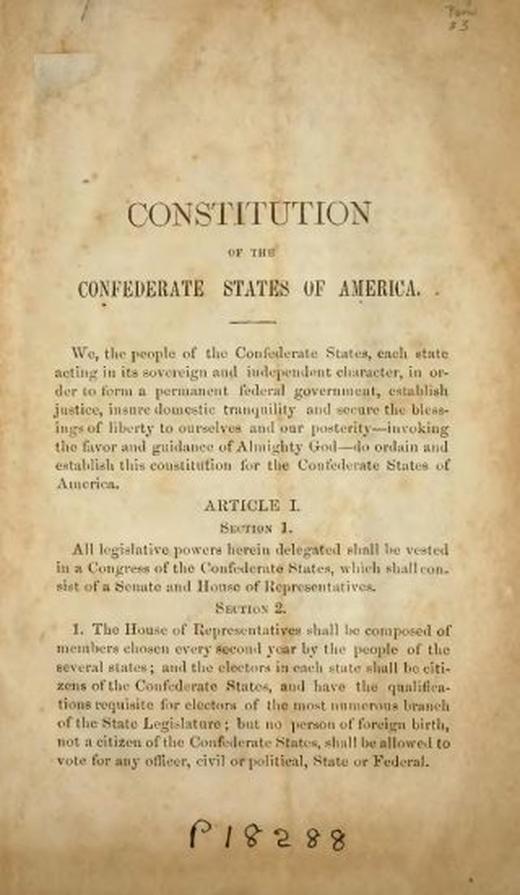

The Confederate Constitution did explicitly protect slavery. This is an undisputed fact documented by historians and the text itself. So, what defense, if any, do people who support the Confederacy offer in light of this reality? Let’s unpack the common arguments, their foundations, and their flaws.

Prepare for a fact-driven journey into how pro-Confederate advocates grapple with the explicit and unapologetic protection of slavery embedded in the Confederate Constitution, and what this means for their claims.

The Lost Cause: A Foundation Built on Shaky Ground

First, many pro-Confederate defenses lean heavily on what’s called the Lost Cause narrative. This movement sprung up soon after the Civil War ended. It reshaped history in a way that downplays slavery’s importance in the Confederacy’s founding and motivations.

The Lost Cause is essentially a pseudo-historical tale made from cherry-picked truths and logical fallacies that spun a kinder, gentler story of the South’s rebellion.

It insists the war wasn’t about slavery, but about states’ rights or economic freedom. The reality? The Confederate government itself explicitly demanded the right to own slaves be protected as a core principle. This disconnect makes the Lost Cause a defense built on ignoring inconvenient facts.

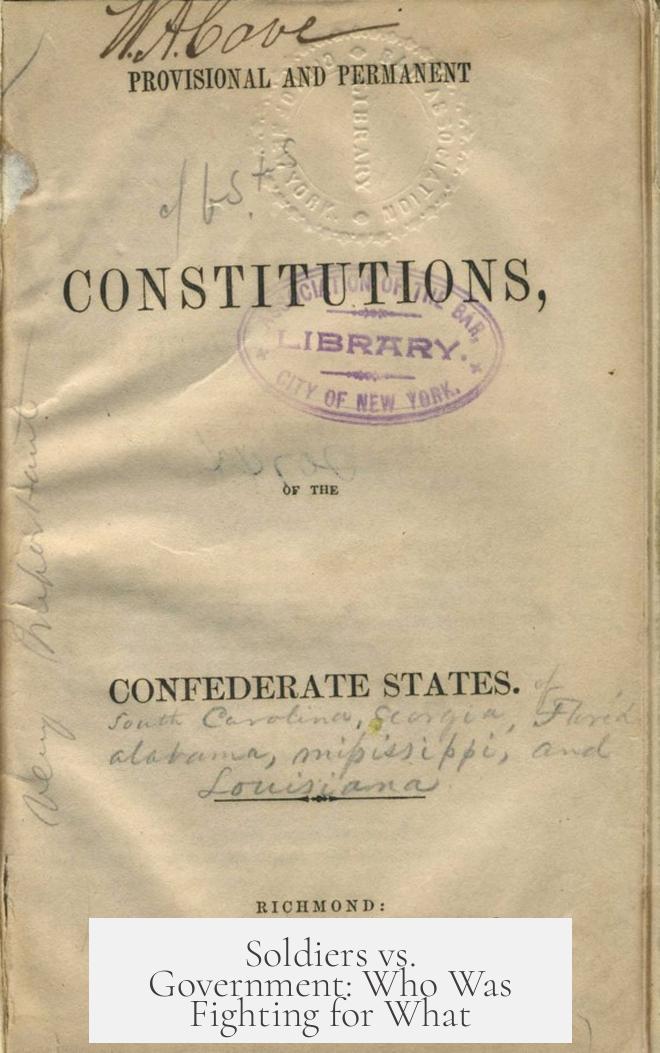

Soldiers vs. Government: Who Was Fighting for What?

One popular defense highlights that 90% of Confederate soldiers never owned slaves. This fact often leads to the claim that these men fought to defend their homes, families, and communities — not slavery directly.

Here’s the twist: You don’t need to own slaves personally to benefit from the institution of slavery. The entire Southern society, economy, and political structure were built on it.

Your everyday Confederate soldier is often portrayed as a devoted, if simple, defender of homeland rather than a champion of slavery.

But it’s critical to separate the individual soldier’s motives from the official intent of the Confederate government, which was clear and explicit about preserving slavery.

This defense sometimes falls into the trap of assuming that if soldiers weren’t slave owners, they were innocent of the cause’s sins. In truth, they were fighting under a government that constitutionally enshrined slavery as a rightful cornerstone.

The North’s Motives: Pure Altruism or Political Game?

Another common pro-Confederate argument points fingers at the North. They say that the Union’s drive to end slavery was more about political and economic power than genuine abolitionism.

A favorite piece of evidence here is Lincoln’s 1862 letter to Horace Greeley, where he wrote:

“My paramount object in this struggle is to save the Union, and not either to save or to destroy slavery.”

Lost Cause proponents interpret this to mean the Northern war effort was centered solely on keeping the United States together, not on ending slavery.

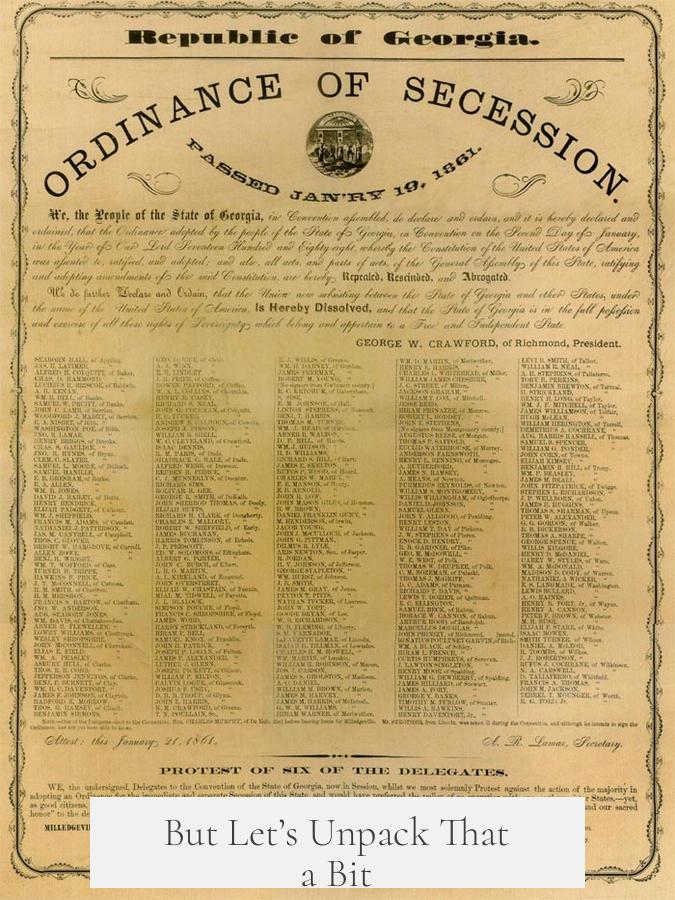

But Let’s Unpack That a Bit

Lincoln’s letter represents his presidential duties and the slow political realities he faced. But he was not alone in the North’s abolitionist movement. Thousands had been fighting legally, politically, and morally for the destruction of slavery for decades.

Lincoln closed that same letter expressing a heartfelt wish “that all men everywhere could be free.” His personal opposition to slavery was clear.

Moreover, government leaders often separate personal beliefs from political practicality. Lincoln had to manage a nation divided; abolition was an eventual goal, but saving the Union was the immediate one.

Thousands of Northern abolitionists—both black and white—risked lives for freedom’s cause, long before and independent of Lincoln’s war strategy.

The Confederate Government’s Core Goal: Preserving Slavery

Despite these complicated motivations on both sides, the Confederate government’s purpose was unmistakenly to preserve slavery.

From secession to Appomattox, every official action referenced slavery as the bedrock of Southern society and politics, founded and fought for in direct opposition to Northern anti-slavery efforts.

Pro-Confederate defenders who downplay or deny this are ignoring the Constitution their leaders crafted. The Confederate Constitution didn’t sneakily protect slavery. It shouted it from the pages.

Southern Fears: Slavery’s Expansion as a Lifeline

Another line of argument focuses on Southern fears, highlighting that many in the South feared not immediate abolition but the end of slavery’s expansion into new territories.

This concern springs from a strategic calculation: slavery needed room to grow or it would falter.

The Haitian Revolution was a nearby historical example that haunted Southern minds—a slave rebellion could erupt if their system weakened.

Political victories like the Dred Scott decision seemed like signs the South could hold slavery’s expansion. When these victories faded, so did confidence in staying in the Union.

Pro-Confederate advocates sometimes argue the war was about protecting this expansion, not just the institution itself.

Summary of the Typical Pro-Confederate Defense

- Most Confederate soldiers weren’t slave owners and fought primarily to defend their homes.

- The North’s motives included political and economic maneuvers, not purely abolitionist ideals.

- Lincoln’s main goal was saving the Union, not ending slavery outright.

- Southern fears centered on slavery’s expansion, crucial for the institution’s survival.

- These defenses rely heavily on the Lost Cause narrative, which distorts historical facts or ignores the Confederate government’s explicit protection of slavery.

What Does This Mean for Pro-Confederate Defenses?

Many defenses center on how and why the war was fought, often distinguishing between individual motivations and government intentions. However, the hard fact remains: The Confederate Constitution, the legal backbone of the Confederacy, explicitly protected slavery.

If someone argues otherwise, they face two problems:

- Their defense conflicts with primary source documents—the Confederate Constitution and official declarations.

- They rely on broad generalizations about individual motives, which do not negate what the government enshrined as its purpose.

This makes any claim denying the Confederate government’s foundational commitment to slavery historically untenable.

Balancing Historical Nuance and Honest Acknowledgment

Can one acknowledge soldiers’ complex motives while condemning the political reality they served? Yes.

Can pro-Confederate people insist the war was about more than slavery without denying slavery’s central role? It’s a tough line, but some attempt this by emphasizing local loyalties and cultural identity.

However, given the exhaustive historical evidence — including statements from Confederate leaders themselves — denying slavery’s centrality remains a losing argument in credible historical debate.

Final Thought: Why Does It Matter?

Understanding the real defense pro-Confederate advocates have allows for a clearer conversation about history, memory, and legacy.

Only by honestly confronting the explicit protection of slavery in the Confederate Constitution can any meaningful dialogue on the topic progress beyond myth and into truth.

After all, history is complex, but it’s not a fairy tale. Knowing this helps society understand the past without the rose tint of nostalgia.