Yes, substantial information exists on how Aristophanes’ plays were staged, drawn from textual references, later artistic evidence, and scholarly reconstruction of ancient Greek theatrical practices. Key features include a small cast of mainly three male actors, the prominent role of the chorus, detailed costumes and masks, use of physical props, and a multi-level stage setup in festivals or theaters such as the Theater of Dionysus.

Aristophanes’ comedies typically relied on three main speaking actors. These actors assumed multiple roles, with the leading actor (protagonist) playing the largest parts, followed by the second with smaller roles, and the third covering minor or auxiliary characters. Occasionally, a fourth actor was necessary. For example, plays like Wasps and Frogs feature moments requiring four speaking parts simultaneously, indicating an added actor.

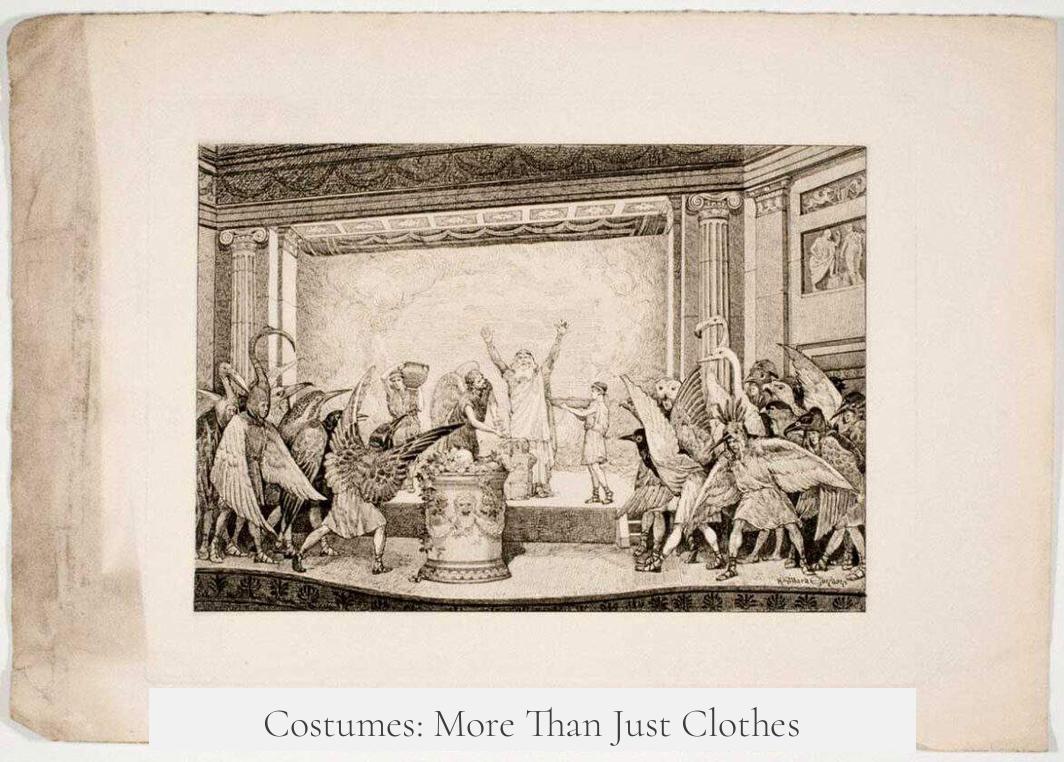

The chorus played an essential role in Aristophanic theater. Composed exclusively of male performers, both adults and adolescents, the chorus danced and sang using costumes that visually represented their themed identities—such as wasps, frogs, or birds. These costumes were likely elaborate and played a critical part in the comedic effect. While precise details are lacking, textual clues reveal moments where choruses changed costumes mid-play to reveal their symbolic creatures, adding visual transformation to the performance.

All actors wore masks and wigs. While no direct images from Aristophanes’ time remain, later depictions confirm that masks featured exaggerated features to convey clear character traits to the audience at a distance. Actors often wore large prosthetic phalluses crafted as wearable props, which could move mechanically. This element supported the prevalent use of sexual humor in the plays and is referenced explicitly in stage directions and dialogue.

Costuming was designed to signal characters’ social status or traits. Aristophanes’ text indicates that characters representing different classes wore distinct attire. For example, in Wasps, the character Hate-Cleon starts in fancy, posh clothes, while Philocleon is dressed as a rough peasant. Slave characters wore clothing traditionally associated with servitude. Although specifics on other characters’ costumes are scarce, there are references to animal characters like dogs and donkeys, which might have prompted costuming or mask use.

Physical props were used extensively, particularly in Wasps. Scenes included benches, wooden dividers reminiscent of courtrooms, cages, pots, ropes, lamps, and other items mentioned in the script. Some props likely existed as simple stage representations, such as a box standing for a caged rooster. These physical objects helped mark scene changes and enhanced the visual storytelling.

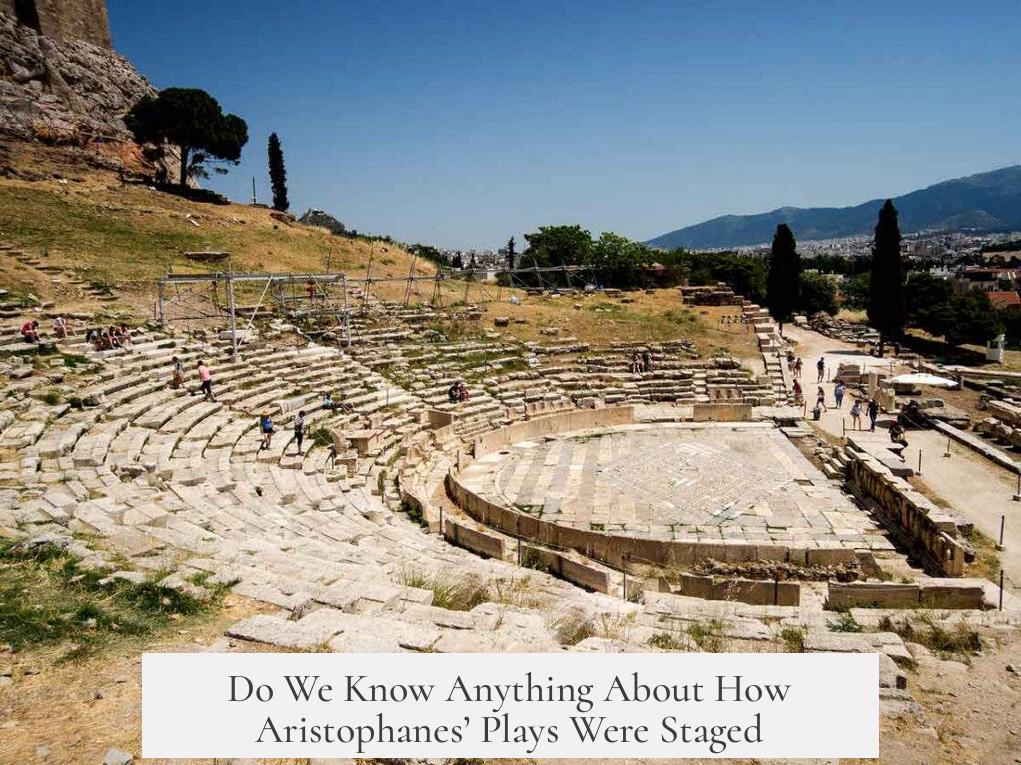

The theater space known as the Theater of Dionysus during Aristophanes’ era featured key elements shaping staging. The audience sat in a tiered arrangement facing an open orchestra where the chorus performed. Above or behind the orchestra stood a raised wooden stage and the skene—a two-story backdrop building with doors and windows for entrances and actor visibility. Actors could enter or exit through multiple levels, including a roof, occasionally referenced in Aristophanes’ scripts. Stage machinery such as a crane (mechane) existed but was seldom utilized in these comedies.

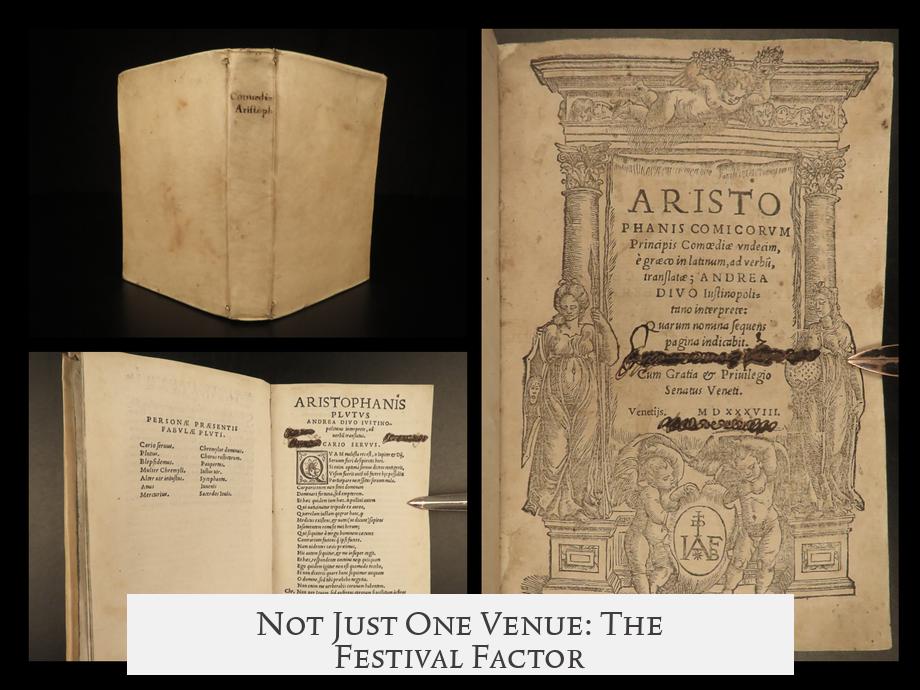

Aristophanes’ works were performed mainly during festivals such as the City Dionysia. Some plays also appeared at the Lenaia festival, possibly staged differently. Though festival venues might have differed, the basic performance setup of seating facing an orchestra, a stage, and a skene likely remained consistent across contexts.

| Aspect | Details |

|---|---|

| Number of Actors | Three main male actors; sometimes a fourth for minor roles. |

| Chorus | Male performers who sang and danced in themed costumes; central to visual identity. |

| Masks & Props | Masks with exaggerated features, wigs, large phallus props; physical props included benches, cages, and household items. |

| Costumes | Costuming reflected character roles and social status; especially notable for slaves and symbolic chorus outfits. |

| Theater Setup | Seating surrounding orchestra; raised stage and two-story skene with doors and windows; roof access for actors. |

| Festivals & Venues | Performances mainly at City Dionysia and Lenaia festivals, possibly with slight venue differences. |

Overall, the staging of Aristophanes’ plays balanced practical limitations with visual spectacle. The small number of actors forced versatility. The chorus provided musical and visual richness. Masks and costumes amplified character traits and humor. Props and stage design aided scene transitions and concrete storytelling. Though unrecoverable in full detail, a vivid sense of lively, imaginative, and comic staging emerges.

- Three main actors performed multiple roles; sometimes a fourth actor was needed.

- The chorus wore symbolic costumes and performed song and dance.

- Actors wore exaggerated masks, wigs, and large phallus props.

- Costumes marked social status and character type.

- Numerous physical props helped define scenes, especially in Wasps.

- Theater included orchestra, raised stage, skene with doors/windows, and roof access.

- Performances occurred mainly at Dionysian festivals but possibly varied by venue.

Do We Know Anything About How Aristophanes’ Plays Were Staged?

Yes! While our knowledge isn’t perfect, scholars have pieced together a fascinating picture of how Aristophanes’ plays were staged in ancient Athens. From actor roles to costumes, props, and the theater itself, the staging breathes life into his biting comedies. Curious how ancient Greeks set the stage for laughs and political jabs? Let’s dive right in.

Aristophanes’ comedies burst with vibrant characters, outlandish choruses, and sharp satire. But how did the theater world of 5th century BCE Athens help bring that to life? Well, buckle up – there’s plenty to unpack, and some fun details that might surprise you.

Three Actors, One Chorus: Less Is More

First off, don’t picture a huge cast bustling around the stage. Aristophanes’ plays traditionally enlisted three main actors who handled all the speaking parts. The star (protagonist) spoke the most, the second actor tackled the supporting roles, and the third filled in smaller characters. Fancy a bit of multitasking? These guys had to be versatile – often switching roles mid-play.

Sometimes, a fourth actor joined the fray for a handful of lines or special scenes. For example, in Wasps, a fourth actor was needed to play both the Kydathenaion Dog and the Plaintiff, since four characters speak on stage simultaneously at one point. The plays Frogs, Acharnians, and possibly Birds also required this rare fourth actor.

Apart from these actors, the chorus was indispensable. Unlike the actors, the chorus didn’t just speak; they sang, danced, and wore costumes, creating a dynamic and lively spectacle for the audience.

All-Male Casts and the Power of Masks

One definite fact: all performers were men, whether adults or adolescents, including those in the chorus. Women didn’t tread the ancient Greek stage.

Actors wore masks and wigs. Unfortunately, we don’t have direct artistic evidence from Aristophanes’ exact time, but slightly later images confirm the use of exaggerated, grotesque masks to signal each character’s identity and amplify their emotions. The masks had enlarged features to convey expressions clearly to the audience, even in the back rows.

Adding to the comedic flair were large, operable phalluses, crafted from leather. These could be manipulated like puppets: raised, lowered, or tucked away. Penis jokes weren’t subtle in Aristophanes’ plays—they brashly strutted center stage. For instance, in Wasps, the stage directions describe characters hoisting themselves by these oversized props. It’s safe to say bawdy humor was a full-body experience.

Costumes: More Than Just Clothes

Costume design wasn’t an afterthought. Clothing reflected each character’s role and social status. For example, in Wasps, Hate-Cleon starts donned in posh attire emphasizing his elite status, while Philocleon wears rugged peasant gear and work boots. Later, Philocleon even changes into sleek Spartan shoes, highlighting his transformation or social aspirations.

Slave characters were easy to spot because of their distinct, recognizable slave garb. This helped the audience immediately grasp the character’s societal place without needing direct voice cues.

The chorus costumes were a mystery layered with spectacle. We know from the chorus of Wasps that they begin in plain citizen-like drapery. Then, in a dramatic reveal, they shed those layers to become buzzing wasps, complete with stingers! The exact mechanics remain unknown, but such transformations hint at a sophisticated and possibly inventive backend staging craft. It seems like an “arms race” of sorts existed to make chorus identities bizarre and hilarious.

Other character costumes—for example, portraying animals like dogs or donkeys—are harder to confirm, but it makes sense that costuming helped signal these identities, perhaps with less subtlety than we’d expect.

Loads of Props? You Bet, Especially in Wasps

You might think ancient Greek comedy was all about words and performance, but no—props played a key role, especially in Wasps. This play references an impressive number of physical objects to mark scene changes and add humor.

For scenes shifting between a house front and lawcourt, Aristophanes mentions benches (typical courtroom furniture), wooden dividers or stockades, and notice boards. These likely appeared on stage to signal changes in location.

There are also numerous quirky props like:

- pots for—well—urine,

- a caged rooster,

- a cheese grater,

- lamps,

- ropes,

- a wreath,

- incense,

- smoke pots to disperse wasps,

- writing tablets,

- and buckets of water

While it’s unclear if each prop was fully realistic or simplified (like a box standing in for a cage), these items show the detailed stagecraft and visual storytelling at play.

The Theater of Dionysus: Setting the Stage

Information about the theater itself during Aristophanes’ era is limited. That said, we know the venue—the Theater of Dionysus—featured the basic components:

- The audience sat in a sprawling seating area (theatron), angled around a central orchestra space where the chorus danced.

- In front of that was a wooden raised platform stage accessible likely via steps.

- Behind the stage stood the skene, a two-story set building with at least one doorway and an upper window for actor interaction.

- The roof of the skene was accessible—in fact, characters often climbed there for comedic or dramatic effect.

Theater machinery like the crane (mechane) existed and could lift actors but appears rarely in Aristophanes’ plays, which might rely more on physical humor and dialogue than dramatic spectaculation.

The skene was decorated, though references are sparse. Decorations likely served as simple but effective backdrops rather than elaborate scenes we expect today.

Not Just One Venue: The Festival Factor

Aristophanes’ plays weren’t always performed in the same place. Different festivals hosted comedic performances, sometimes with different staging setups. For instance, four of his known plays debuted at the Lenaia festival, which possibly used a venue other than the Theater of Dionysus.

Despite this, it’s broadly agreed the basic setup was similar: an audience area facing an orchestra and raised stage, with some backdrop or skene structure. So no matter the venue, fundamental staging elements remained constant.

Why Does Any of This Matter?

Understanding Aristophanes’ staging illuminates how his sharp satire and physical comedy blasted off in ancient Athens. It shows the brilliant craftsmanship behind what many naïvely think of as simple slapstick. The combination of versatile actors, exaggerated masks, bawdy props, and transforming choruses crafted a visual feast complementing his clever words.

Imagine watching a chorus morph into giant buzzing wasps or a character hoisting himself by a giant leather phallus—this was comedy that grabbed your attention every second. And that’s before Aristophanes started skewering politicians or poking fun at tragedy conventions!

These staging choices reflect unique Athenian culture and theatrical innovation, showcasing how comedians balanced humor, political commentary, and spectacle over two millennia ago.

Curious To Learn More?

If this backstage peek sparks your interest, check out A Guide to Ancient Greek Drama by Ian Storey and Arlene Allen (Blackwell, 2005). It’s a treasure trove for anyone fascinated by how ancient theater worked and why Aristophanes remains so fresh and funny today.

So next time you hear a joke about buzzing wasps or oversized phalluses in a comedy (or well, anywhere else), remember: Aristophanes practically invented that shtick, staging it with flair, costumes, and enough props to fill a Greek hardware store.

In conclusion, we do know quite a bit about how Aristophanes’ plays were staged—three core actors (sometimes a fourth), an inventive chorus with whiz-bang costumes, abundant props (especially in Wasps), and a well-structured but flexible theater space. It’s a lively, visually rich tradition that makes ancient Greek comedy a vivid experience, not just dusty old texts.

How many actors performed speaking parts in Aristophanes’ plays?

Typically, there were three main actors with speaking roles. Sometimes a fourth actor appeared for minor parts, like in *Wasps* and *Frogs*. The chorus also performed but did not have individual speaking parts.

Did Aristophanes’ actors use masks and costumes?

Yes, all male actors wore exaggerated masks and wigs. They also used large, movable phallus props for comedic effect. Costumes reflected the character’s social status or role, such as slaves in typical slave garb.

What role did the chorus play in staging and costume design?

The chorus sang and danced in costume. Their outfits matched the play’s theme, like wasp costumes in *Wasps*. They started in simple clothing and revealed elaborate disguises during the play. This visual identity was key to comedy.

Were physical props commonly used on stage?

Yes, especially in *Wasps* we see many references to physical props like benches, cages, pots, and lamps. They helped shift scenes and added realism, though some may have been simple symbolic representations.

What do we know about the theater space for Aristophanes’ plays?

Theater of Dionysus had a seated area, orchestra for chorus dances, and a raised stage with a wooden backdrop called the skene. Actors used doors, windows, and sometimes the roof. There was stage machinery like a crane, but it was rarely used in comedies.