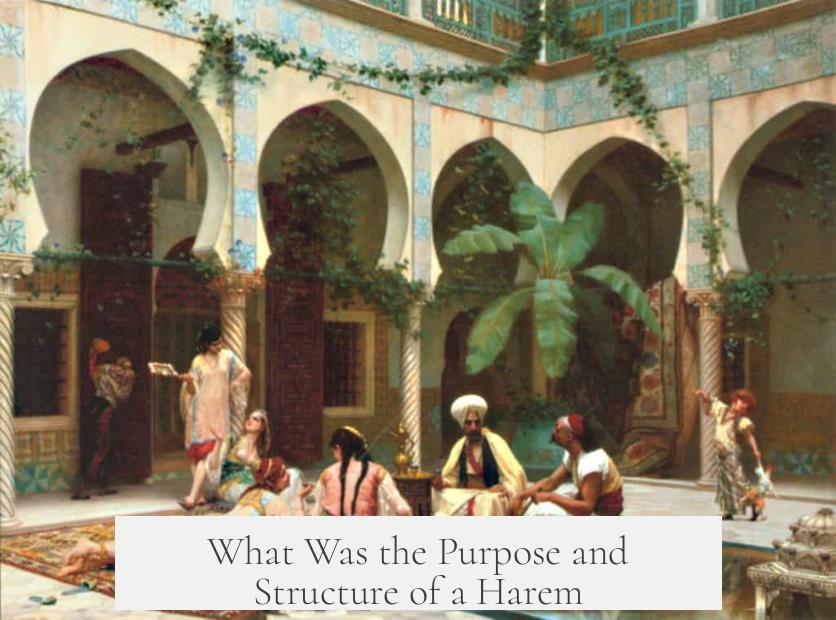

The purpose and structure of a harem center on its role as a domestic household within Islamic society, composed of free and enslaved women who performed specific social and sexual functions under legal and cultural frameworks, rather than being a prison or a space of arbitrary confinement or exploitation.

A harem was a private domestic space that housed women related by free status or servitude to the male head of the household. Unlike popular myths, it was not a locked or isolated prison but rather an extended household in which members had defined roles and relative freedom of movement according to their duties and status. Both free women, such as wives, and enslaved women, such as concubines, could leave when required or desired, highlighting the household’s dynamic nature.

The social composition inside the harem included a clear distinction between free persons and enslaved persons. This divide reflected the broader societal structure of the time and carried over into the household. “Servants” as a separate category did not specifically exist; instead, the women’s roles aligned with their legal statuses. Free Muslim women were typically wives, while enslaved women often served as concubines or helpers in daily domestic tasks. These roles were entrenched within the legal frameworks of the period.

The functions of the harem were both domestic and sexual. Women managed household affairs such as overseeing servants, childrearing, and other daily activities. Sexual relations within the harem followed Islamic law and customs, with marriage and concubinage focusing on lineage, inheritance, and property rights rather than romantic love or attraction. For example, the rights to a child’s inheritance often determined the legal recognition of relationships.

Exceptional relationships, such as Suleiman the Magnificent’s emotional bond with Hurrem Sultan (Roxelana), did exist. However, power imbalances inherent in the system shaped these relationships, balancing personal affection with social and political considerations.

Legally, the status of women in the harem could change. Notably, enslaved women who bore children to the male head gained freedom on his death, a practice institutionalized within Islamic law to protect offspring rights. Meanwhile, free wives returning to their families after widowhood also demonstrated fluidity in status and household affiliation throughout their lives.

The harem also reflected the cultural expectations of Islamic modesty. Inside the private space, women were not required to wear hijab or other veiling garments. However, veiling was mandatory when they left the harem, marking the boundary between private family life and public society. This requirement emphasized the cultural and religious emphasis on modesty and privacy for women during the medieval and Ottoman eras.

| Aspect | Details |

|---|---|

| Purpose | Household management, social order, sexual relations under Islamic law |

| Composition | Free Muslim wives and enslaved concubines, no separate “servants” category |

| Legal Status | Enslaved concubines could gain freedom upon bearing children; wives returned to families after widowhood |

| Movement | Residents could leave freely as required or desired |

| Cultural Practices | Veiling mandatory outside the harem; relaxed modesty rules inside |

Common misconceptions about the harem often portray it as a place of unrestricted sexual indulgence or imprisonment. In reality, sexual relations adhered strictly to Islamic standards, forbidding illicit acts and emphasizing proper lineage and property rights. The harem existed as an organized domestic entity where social order and legal norms prevailed.

The harem’s structure balanced private and public spheres. It was integral to sustaining family lineage, managing household affairs, and maintaining social hierarchies. Women’s roles, whether free or enslaved, involved complex interactions within a framework of Islamic law and cultural tradition rather than purely personal or emotional motives.

- A harem functioned as a household unit with specific social roles and legal frameworks, not a prison.

- It contained free Muslim wives and enslaved concubines who performed domestic and sexual roles.

- Residents had freedom of movement in accordance with duties and social status.

- Sexual relationships focused on inheritance and property rights rather than romance.

- Enslaved women bearing children could gain freedom; widowed free women returned to their families.

- Women adhered to modesty codes within and outside the harem, veiling when in public.

- The harem maintained social order and followed Islamic legal principles, contradicting myths of confinement or indiscriminate exploitation.

What Was the Purpose and Structure of a Harem?

First things first: a harem is a household, not a prison. This fact alone flips many common stereotypes on their heads. While Hollywood and sensationalist tales often paint harems as gilded cages, the historical reality is quite different—and more intricate than you might expect.

So, what exactly was the purpose and structure of a harem? In essence, it was an extended domestic unit—a lively household where free and enslaved women lived, worked, and played important social roles. Let’s take a detailed and eye-opening journey into this fascinating part of Ottoman and medieval Islamic life.

A Household, Not a Cage

The first and most crucial point is understanding that a harem was not a locked away prison. Both free women and enslaved residents could leave whenever their responsibilities required or when they wished to. It’s like a bustling family home with internal roles and freedoms, rather than a forcible confinement zone.

This distinction is important. Harems functioned as private domestic spaces within a household. Imagine a complex social environment where everyone knows their role but still enjoys relative freedom and community. That household wasn’t about imprisoning women—it was about managing a large, often powerful family network.

Who Lived in the Harem?

The residents included both free people and enslaved individuals. Contrary to some assumptions, there was no middle category between slaves and free persons. If the Ottomans had something akin to “indentured servitude,” it’s not well documented. This meant roles and status inside the harem closely mirrored broader societal distinctions.

Free women—often wives or close relatives of the household head—maintained their social roles consistent with life outside. Enslaved women, meanwhile, had defined duties but were also integrated into the household’s social fabric, not isolated from it.

Domestic Duties and Sexual Roles

Harems were busy with day-to-day household management. Cooking, cleaning, childcare, and organizing social functions made up much of daily life. Of course, sexual relationships were a part of the harem too. Certain women—free wives or enslaved concubines—were connected to the male head of household sexually.

However, this was framed by the legal and social norms of the time, not modern romantic notions. Marriage and sex often related to inheritance and property rights, not love or passion. That isn’t to say love was absent; take the famous relationship of Sultan Suleiman the Magnificent and Hurrem Sultan (Roxelana). Their bond was exceptional, suggesting emotional closeness, though intertwined with power dynamics.

Legal Status and Transitions

The legal system prescribed interesting rules about status. For instance, an enslaved woman who bore a son to her master would gain freedom when he passed away. On the other hand, free Muslim wives, upon widowhood, typically returned to their parental homes. These laws highlight how personal status was linked to familial relationships and religious guidelines rather than arbitrary imprisonment.

Private Life vs. Public Expectations

Inside the harem, Islamic modesty rules were relaxed. Women did not have to wear hijabs or veils indoors—comfort and privacy ruled. But once outside, these modesty codes were strictly followed. This strict boundary between public appearance and private life adds nuance. The harem was a subjective safe space — a place for women to live and work without external pressures. It let them breathe without the ever-watchful eye of societal judgment.

Setting the Record Straight: Common Misconceptions

Many outside observers, especially colonial or Western sources, painted harems as “sex dungeons” or dens of exploitation. These labels are not only misleading—they distort the fundamental purpose of the harem. Sexual relations inside followed Islamic law strictly. Unlawful liaisons were offenses and not tolerated.

So, a harem was neither a den of debauchery nor simply a household of enslaved women. It was a multifaceted institution balancing family life, legal frameworks, social order, and intimate relationships.

Why Does This Matter Today?

Understanding the true nature of harems helps dismantle enduring myths that shape biased views about Islamic culture and history. It paints a more human, complex picture—more like a large, well-organized family that manages roles and traditions than a prison or brothel. Wouldn’t you agree gaining clarity here enriches our global historical perspective?

If you ever thought about harems as locked away spaces of oppression—think again. They were lively households with structure, rules, and freedom within social frameworks. Next time you hear the word “harem,” picture not a dungeon but a bustling home.

| Harem Element | Purpose/Role | Notes |

|---|---|---|

| Household Unit | Domestic management and family organization | Not confined; residents had freedom within duties |

| Residents | Free women (wives, relatives) and enslaved concubines | Legal status varied; no “servants” category distinct from slaves |

| Sexual Relationships | Framed by Islamic law and inheritance rules | Rare cases of emotional bonds (e.g. Suleiman and Hurrem) |

| Legal Status Changes | Freedom granted to enslaved mothers after master’s death | Free wives returned home after widowhood |

| Modesty Practices | Veiling inside the harem was optional; mandatory outside | Separate private and public norms |

In summary, the harem was a nuanced and multi-functional institution. It was a household designed to balance social order, domestic life, lawful intimacy, and cultural norms. The story it tells is far richer than myths and assumptions suggest.

What was the primary purpose of a harem?

The harem functioned as a household, managing domestic tasks and social order. It housed free and enslaved women who had roles in family life and sexual relations based on Islamic law.

Was the harem a place of imprisonment?

No. The harem was not a prison. Residents, whether free or enslaved, could leave when their duties required or as they chose.

How were social roles organized inside the harem?

There was a clear distinction between free women and enslaved women. Their roles mirrored wider social structures, with no special category like servants.

What was the legal status of enslaved women in the harem?

An enslaved woman who bore a child to the household head gained freedom after his death. Free wives returned to their families if widowed.

How did cultural customs affect women inside the harem?

Inside the harem, women were exempt from wearing veils. When leaving, strict modesty rules applied, requiring them to cover according to social customs.

Did sexual relations in the harem follow any rules?

All sexual activity was governed by Islamic law. Relationships were connected to marriage, inheritance, and social order, not casual or unrestricted encounters.