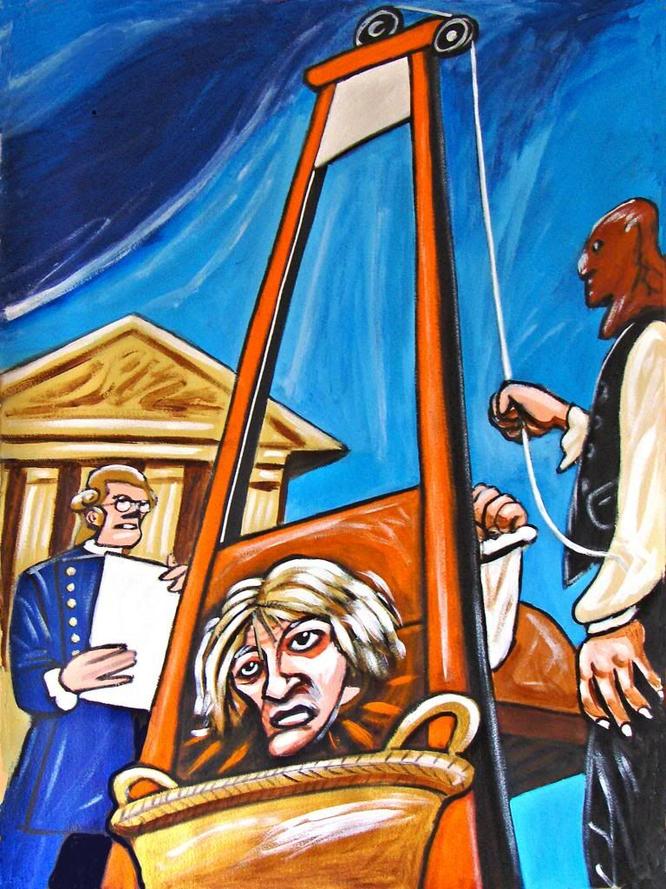

The guillotine became the tool of choice for executing the French aristocracy not because it was designed to target them, but because it was seen as a more humane, efficient, and class-neutral method of execution during the French Revolution.

Before the Revolution, execution methods were closely tied to social class. Nobility often received beheading by sword, which required skill and was considered an honorable death. Commoners faced strangulation by rope, hanging, or other harsher means. These divergent methods symbolized—and reinforced—the rigid class distinctions of the Ancien Régime. The guillotine broke this tradition by providing one method for all condemned individuals, abolishing distinctions based on social status.

Executions before the guillotine were often cruel, inefficient, and could prolong suffering. Beheading with a sword or axe was difficult and prone to error. A famous example is Mary Queen of Scots’ execution, which did not succeed with a single stroke. Other methods, like firing squads, sometimes led to slow deaths, and hangings often caused condemned prisoners to kick for minutes after death. Such inefficiencies were unacceptable during the radical phase of the Revolution, especially during the Terror, when executions numbered about 30 a day in Paris alone. The guillotine’s speed and reliability ensured quick, painless death and reduced suffering to a minimum.

Moreover, the guillotine did not require a highly skilled executioner, unlike sword beheadings. This was crucial when large-scale executions took place. Whereas a botched execution could cause public outcry or undermine revolutionary legitimacy, the guillotine delivered swift results. This efficiency met the Revolution’s desire for rapid, no-nonsense justice without lengthy speeches or prayers that could rally sympathy for the condemned.

Despite its association with the aristocracy due to the high-profile executions of nobles like King Louis XVI and Marie Antoinette, the majority of guillotine victims were not aristocrats. Data shows that only about 8.5% of the approximately 13,000 individuals executed during the Revolution were nobles. About 31% were workers, 18% peasants, and 25% bourgeois, which included merchants and shopkeepers. The guillotine was a tool of revolutionary justice applied broadly across class lines, reflecting political aims rather than a specific focus on the aristocracy.

The choice of the guillotine also reflected evolving social and legislative priorities of the Revolution. The newly established National Assembly sought to replace the brutal and torturous execution methods common under the Ancien Régime. Public executions before the Revolution could be lengthy spectacles involving excruciating forms of torture. One notorious case was the execution of Robert-François Damiens, who attempted to assassinate King Louis XV and was executed by a gruesome process of tearing and burning. Voltaire criticized similarly horrific punishments, like the breaking wheel and burning of the merchant Jean Calas, who was wrongfully condemned.

The guillotine offered a symbol of enlightened justice by ending the era of cruel, unusual, and prolonged suffering. It gave condemned individuals a quick death, which was considered more humane and in line with Enlightenment values. Additionally, adopting a uniform execution device helped regulate and control public violence. The Revolution sought to curb the chaotic and often random mob violence perpetrated by Jacobin mobs who previously lynched suspected enemies in the streets. Public executions with the guillotine became official, state-controlled events that aimed to maintain order and discourage extrajudicial killings.

In essence, the guillotine’s role extended beyond execution of the elite. It was a practical, ideological, and humanitarian tool in the revolutionary government’s justice system. It embodied ideals of equality by applying the same fate to all, regardless of status. It improved the efficiency and humanity of capital punishment, while simultaneously helping to establish state authority over revolutionary fervor.

| Reasons the Guillotine Was Chosen | Details |

|---|---|

| Humane execution method | Quick, painless death, eliminated cruel torture |

| Class-neutral application | Same method regardless of social rank, ending class privilege in execution |

| Efficient and skill-independent | No need for expert swordsmen, prevented botched executions |

| Control over mob violence | Reduced random lynchings by Jacobin mobs by formalizing executions |

| Symbol of revolutionary justice | Reflected Enlightenment ideals and state authority |

- The guillotine was not specially designed to kill aristocrats but was a humane alternative.

- It abolished class distinctions in execution methods, treating all equally.

- Its quick, efficient operation suited the demands of mass executions during the Terror.

- The majority of those executed by guillotine were commoners, not nobility.

- It symbolized revolutionary ideals against cruel old regime punishments and helped suppress mob violence.

Why Was the Guillotine the Tool of Choice for Killing the French Aristocracy?

The guillotine became the preferred method during the French Revolution because it was quick, efficient, and, above all, *humane*—or at least as humane as public execution could get. Most importantly, it wiped away the messy class distinctions of punishment while appealing to revolutionary ideals.

Sounds straightforward, right? But the guillotine’s story runs deeper than just dramatic beheadings or revolutionary spectacle.

Let’s slice through the myths.

The Guillotine and Humane Execution: More Than Just a Clever Machine

First, the guillotine wasn’t a weapon designed solely to torment aristocrats. It was created with a surprisingly compassionate aim—to make executions less painful and more humane.

“The aristocracy wasn’t chosen in particular. The idea was that the guillotine was a humane way of performing executions.”

Before the guillotine, execution methods were all over the map—and mostly grisly. Nobles might receive a quick beheading by sword, but commoners had it worse—strangulation, hanging, or other tortures. It wasn’t fair; death was handled with blatant social bias.

Enter the guillotine, an equalizer of death. It didn’t care about your class or title. Everyone met the same fast, mechanical end. One fall of the blade, no suffering, and to the point.

Execution Methods: The Guillotine vs. The Old School

Imagine being the executioner back then— wielding a sword or axe meant nerves of steel and excellent aim. One slip meant botched endings and prolonged suffering. Remember Mary Queen of Scots’ execution? It couldn’t be done in just one chop—a royal mess.

Other types weren’t any more pleasant. Firing squads could miss, slow kills by hanging might leave the condemned kicking for minutes—the spectacle was gruesome and inefficient.

The guillotine was an engineer’s dream: reliable, swift, and requiring minimal skill. No messy headsman slip-ups. It made executions precise, clean, and most importantly, fast.

During the most intense phase of the Terror, the guillotine sliced through as many as 30 people a day in Paris alone. Imagine the grim efficiency demanded!

Was It Really Just for the Aristocracy?

Here’s an unexpected twist: despite the guillotine’s notorious link with nobles, aristocrats made up less than 10% of its victims.

Statistics reveal a broader story:

- About 8.5% were nobility.

- 6% were priests.

- 31% were workers.

- 18% were peasants.

- And 25% were bourgeoisie—merchants and shopkeepers.

Executions could see a marquis standing beside a shoemaker, a thief, and even several nuns all facing the same blade on the same day. This emphasizes that the guillotine was the equalizer of death, not just a weapon wielded against the aristocracy.

Political Purpose: Regulating Death and Controlling Chaos

Beyond humaneness and efficiency, the guillotine played a critical political role.

The revolutionary government wanted to curb the chaos of violent mobs, who might otherwise hang innocent people randomly from lampposts or worse. They needed a controlled, public execution method that was swift and avoided the torture spectacles of the Old Regime.

Think about the gruesome torture of Robert-François Damiens who tried to assassinate Louis XV—torn apart by horses and burned alive. Or the protestant merchant Jean Calas, broken on the wheel and then burned. These were cruel punishments designed to terrorize. The guillotine, by contrast, promised a quick death with none of that prolonged agony.

Public executions became less about rage and spectacle and more about calculated political theater that embodied revolutionary ideals: equality, justice, and a staunch opposition to the cruelty of the past.

So, Why The Guillotine for the Aristocracy?

It’s tempting to think the guillotine was the French Revolution’s way of delivering poetic justice to the aristocrats. But in reality, it was chosen because it was the most practical, humane, and politically useful execution method available.

Its swift blade served the revolution’s demand for efficiency and fairness in death. By removing class-based distinctions from how punishment was carried out, it symbolized the new order—a society claiming justice for all.

And the bloody irony? Though famous for ending noble heads, it was an equalizer that took countless lives across every walk of life.

Final Thoughts: What Can We Learn?

The guillotine wasn’t just about killing aristocrats; it was a practical invention wrapped in the revolutionary ideals of humanity and justice, while also taming mob violence.

It teaches us something important: even in moments charged with violence and upheaval, societies strive for fairness and order—even if that order comes dressed in steel and blood.

So next time you picture the guillotine, remember—it’s not just a symbol of terror but a complex tool shaped by politics, efficiency, and a very dark sense of equality.

Interested in more historical twists? What other inventions or ideas do you think history got wrong at first glance? Feel free to share your thoughts below!