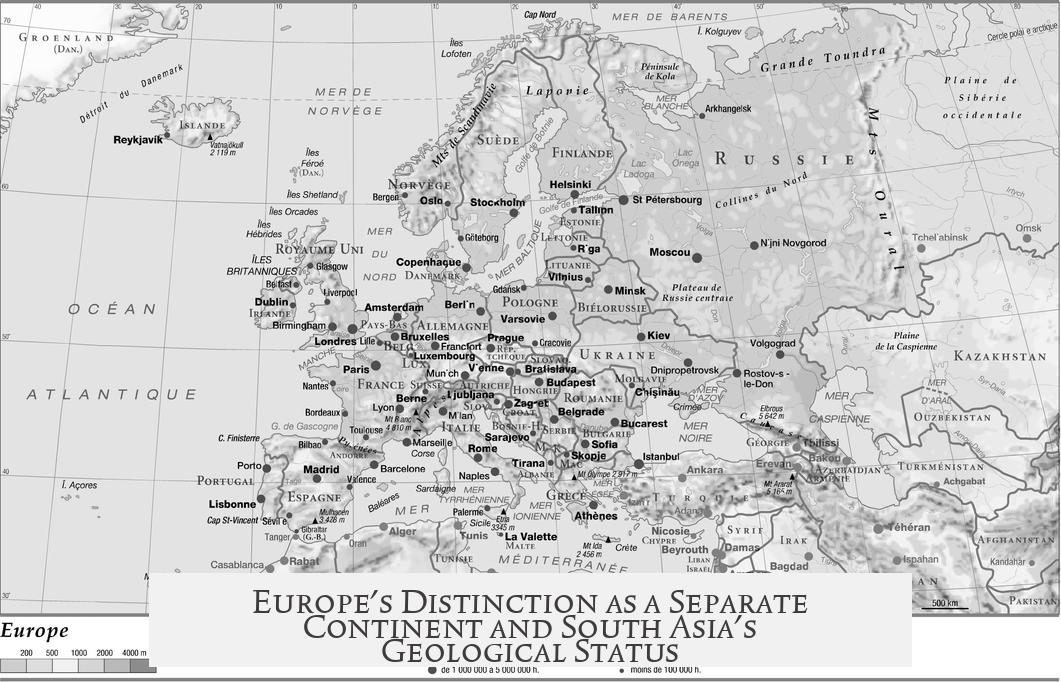

Europe is considered a separate continent primarily due to historical, cultural, and ideological factors rather than strict scientific reasons. In contrast, South Asia is not classified as a separate continent because it forms part of the larger Eurasian landmass based on geological and tectonic evidence.

The concept of continents does not have a single, universally precise definition. It often blends geographical, cultural, and historical perspectives. The term “continent” may reflect widely accepted socio-cultural zones or significant geological features. Europe’s status as a distinct continent owes more to cultural identity and ancient traditions than to clear physical separations.

Europe’s classification originates from ancient Greek geography. Greeks distinguished Europe and Asia as different landmasses. They named lands west of the Aegean and Black Seas “Europe” and lands to the east “Asia.” Early Greek scholars like Anaximandros of Miletos and historian Herodotos placed the boundary between Europe and Asia at the Phasis River, marking a cultural and geographical divide that lasted centuries.

Europe’s identity was reinforced over time by sociopolitical and cultural distinctions. Ancient Greek authors linked “Asia” with the Persian Empire, which they viewed negatively. This ideological divide gave Europe a positive cultural identity contrasted with Asia. Aristotle highlighted differences in peoples and customs between the two regions, emphasizing cultural rather than geographical differences.

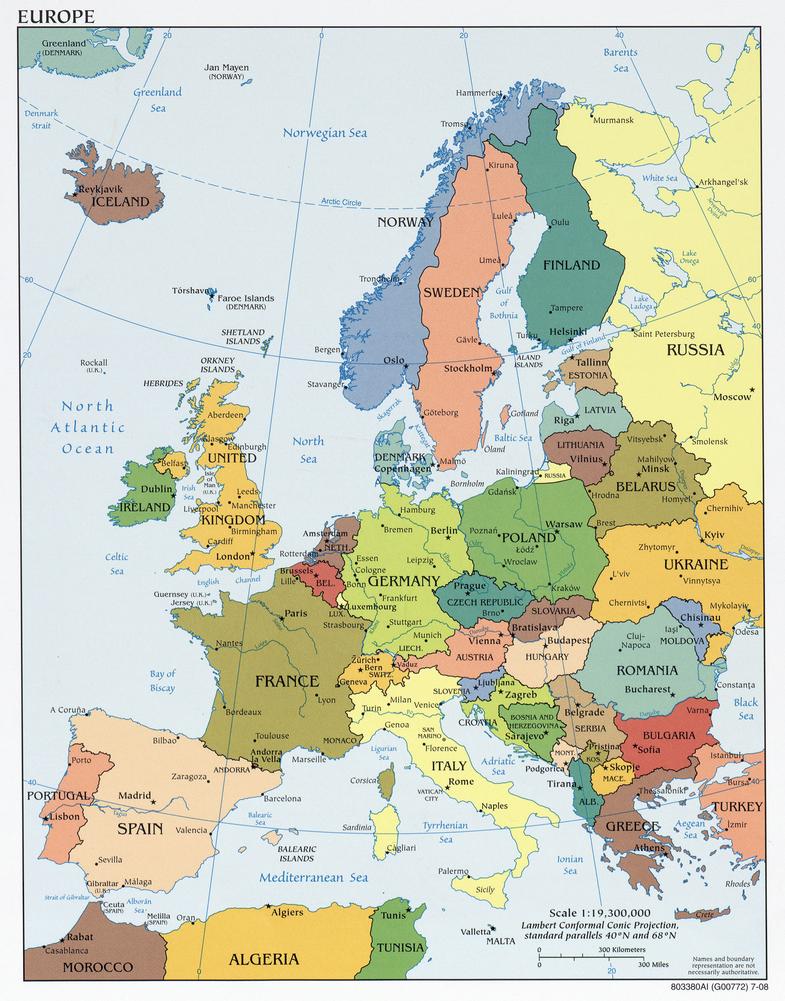

This legacy persists today. Modern geographic boundaries between Europe and Asia remain largely symbolic and follow historical lines rather than strict physical barriers. For example, islands like Cyprus, geographically closer to Asia, are considered part of Europe due to cultural and political ties such as EU membership. Similarly, countries like Georgia, straddling geographic boundaries, align with Europe culturally and politically.

By contrast, South Asia is considered part of the Asian continent based on strong geological evidence. It is often called the Indian subcontinent in scientific contexts, reflecting its tectonic origin. This landmass separated from the ancient supercontinent Pangea during the Cretaceous period. The collision of the Indian tectonic plate with the Eurasian plate formed the Himalayan mountain range, physically connecting South Asia within the Asian continent.

Unlike Europe, South Asia’s identity as a region is not derived from cultural or ideological separations but from geological continuity. Its categorization as a subcontinent highlights its scientific distinctiveness but does not elevate its status to an independent continent. This aligns with broader continental classifications, where tectonic data play a central role.

The inconsistencies and ambiguities in continent definitions illustrate the flexible nature of geographical classifications. For example, terms like “peninsula” or labels for regions (e.g., Balkans) are often more cultural or historic than scientific. Additionally, historical connections like Eurasia’s land continuity with Africa before the Suez Canal show that continents are not always separated by large physical barriers.

In essence, continents are partly social constructs shaped by history and human perception. Europe’s separation reflects deep-rooted cultural identities and historical naming practices. South Asia, however, remains part of Asia due to its geological context and the absence of a strong socio-cultural movement defining it as a separate continent.

| Aspect | Europe | South Asia |

|---|---|---|

| Basis for Classification | Historical, cultural, ideological | Geological, tectonic |

| Origin of Name/Boundary | Ancient Greek geography and philosophy | Indian subcontinent tectonic formation |

| Physical Separation | Mostly symbolic (Ural Mountains, rivers) | Part of continuous Eurasian landmass |

| Cultural Homogeneity | Relatively homogeneous historically | Highly diverse, multiethnic |

| Current Recognition | Widely accepted separate continent | Region/subcontinent within Asia |

- Europe’s continental status arises from ancient Greek naming and cultural divisions.

- South Asia is geologically part of Eurasia, classified as a subcontinent, not a separate continent.

- Definitions of continents blend scientific, cultural, and historical views and often vary by context.

- Geographical terms frequently reflect cultural and political identities alongside or instead of strict geography.

Why is Europe Considered Its Own Separate Continent? Why is South Asia Not?

Europe is considered a separate continent mainly due to deep-rooted historical, cultural, and ideological reasons, whereas South Asia remains part of the larger Eurasian continent because it is scientifically defined as a tectonic subregion rather than an independent continent. That’s the quick answer—but hang on. This question opens a fascinating window into how we shape and define our world beyond just maps and geology.

Have you ever wondered why maps show Europe as distinct from Asia, despite being one massive landmass called Eurasia? And why South Asia, with its unique cultures and geography, just blends into Asia rather than standing on its own? The reasons are anything but straightforward.

The Loose Definition of “Continent”

First things first, is the word “continent” even well-defined? Not really. The term carries a lot of baggage—historical, cultural, even political. Geographically and scientifically, continents are often not clearly separable. Instead, continents are usually a mix of cultural and historical concepts layered on physical geography. The notion of continents isn’t a hard science concept; it’s part convention, part storytelling.

Take Europe, for instance: its borders aren’t clearly a natural break on a huge landmass. Instead, Europe exists as a separate continent because it developed a distinct identity early on. The word “continent” itself can be very flexible. Europe’s status mainly stems from centuries of tradition and the cultural groupings that emerged from ancient times.

The Ancient Greek Origins of Europe’s Continental Status

Let’s step back thousands of years. The ancient Greeks divided the known world between Europe and Asia primarily based on their own experiences and politics. The coastline west of the Aegean and Black Seas became “Europe,” while the lands across those waters were “Asia.” This made sense at the time—not as a strict geographical fact but as a way of organizing friendly neighbors and rivals.

Greek thinkers like Anaximandros and Herodotos set a boundary at the Phasis River, and the split stuck.

The Greeks even loaded the name “Asia” with negative meaning, by associating it with the despised Achaemenid Persian Empire. Europe became a symbol of “us”—civilization, democracy, and Western values—while Asia was cast as “them.” Over time, these ideological and socio-cultural distinctions became entrenched and echoed by later European geographers.

Europe’s Cultural Homogeneity Versus Asia’s Diversity

Unlike the massive multi-ethnic, multi-religious, and multi-lingual Asian continent, Europe has long been relatively more culturally homogeneous. This bolstered the sense of Europe as a unified “continent.” The European Union, which includes places like Cyprus—physically closer to Asia—further demonstrates how cultural and political factors trump strict geography.

- Cyprus is officially part of the EU, despite its geographical placement nearer Asia.

- Georgia, lying at the crossroads of Europe and Asia, identifies culturally and politically as European.

These examples show that continent definitions can depend heavily on cultural and political identity.

South Asia: The Indian Subcontinent as a Geological Subregion

Now, what about South Asia? Scientifically, this region—often called the Indian subcontinent—has a distinct geological history. It once existed as the “Insular India” landmass, which drifted away from the supercontinent Pangaea. It collided with the Eurasian plate millions of years ago, creating the Himalayas.

Unlike Europe, South Asia is recognized by scientists mainly for its tectonic identity rather than standalone cultural or historical separateness. It’s a prominent subregion within the massive tectonic unit that is Eurasia—not an independent continent.

This classification is evidence of scientific criteria being more influential here than the historical or ideological reasons responsible for Europe’s status.

When Geography Meets Culture: Fluid Definitions and Exceptions

The story of continents gets even more tangled when you consider other terms like “peninsula.” The Balkans, for example, are often called a peninsula—though this label sometimes contradicts geographical or historical facts. Yet, local populations, the EU, and even the UN widely accept it because regional identity often trumps rigid definitions.

Continent boundaries ignore past land connections as well. For example, Eurasia could be expanded to include Africa—the continents were once joined before the Suez Canal came into being. Similarly, North and South America were connected before the Panama Canal.

So, why cling to the Europe-Asia division? Because it’s not just about land or science. It’s about identity and stories passed down for millennia.

Wrapping It Up: More History Than Geology

Europe’s status as a continent is a fascinating example of how geographical terms come loaded with meaning beyond physical landmasses. Ancient Greek naming, cultural distinctions, ideological biases, and political history have kept the Europe-Asia boundary alive and meaningful.

South Asia, by contrast, rests firmly within scientific and tectonic reasoning. It remains a subcontinent because it is a distinct geological unit, not because of historical or cultural separateness from Asia as a whole.

So next time you glance at a world map and wonder why certain borders exist, remember: continents are as much stories as they are physical facts. Geography sometimes tells a tale, but history writes the script.

Why Does This Matter?

- Understanding the fluidity of “continent” helps us better grasp global diversity and connectedness.

- It reminds us that cultural identity can shape how we view the world, often trumping science.

- For travelers, educators, and curious minds alike, it pushes us to question what we take for granted on maps.

At the end of the day, the answer to why Europe stands apart and South Asia does not lies in the mix of science, history, culture, and ideology—each playing their part in mapping our human story.