John Milton’s epic poem “Paradise Lost” achieves its historic and enduring success not as a simple retelling of Genesis but as a profound expansion and reinterpretation of biblical themes, classical literature, and contemporary political concerns. The poem transcends its scriptural origin by introducing complex characters, especially a deeply nuanced Satan, and weaving in broader theological and allegorical elements. Milton’s work creatively combines elements from Genesis, Revelations, and classical epics, setting it apart as a unique literary masterpiece rather than a straightforward biblical narrative.

Milton’s “Paradise Lost” diverges significantly from Genesis in scope and theme. While Genesis focuses on the creation story and the fall of man in a concise form, Milton expands this with an epic structure that frames the biblical events within a cosmic battle. The poem begins not with the Creation but with an extended recounting of the Angelic War, where Satan and his followers rebel against God. This addition is Milton’s innovation—a detailed backstory not found in Genesis, giving readers insight into the origins of evil and rebellion. This makes the poem a much broader theological exploration.

One major difference lies in Milton’s portrayal of Satan. The Bible itself mentions the “Serpent” in Genesis, but it does not identify him explicitly with Satan or narrate his backstory. Milton invents a rich characterization of Satan as a proud, eloquent rebel, famously declaring, “Better to reign in Hell than serve in Heaven.” This complex characterization engages readers by exploring moral ambiguity and internal conflict. Satan emerges almost as a tragic hero, a narrative approach that invites sympathy despite his role as the antagonist.

Milton’s theological framework also reshapes divine characters. God is omnipotent and omniscient, and the fall of mankind becomes part of His greater plan, not a failure of will. The Son of God, described under a doctrine called subordinatism, holds a role secondary to the Father, differing from traditional Trinitarian views. These theological nuances offer readers a layered understanding of divine justice and mercy.

Contemporary issues in Milton’s time breathe life into the epic. His experience during the English Civil War colors the poem’s political and religious allegory. The poem mirrors Milton’s support for the Parliamentarians and his own calls for regicide, embedding his contentious political ideals within the cosmic conflict. For instance, Book VI, where Satan and his angels wage war using inventions akin to gunpowder cannons, reflects 17th-century warfare, drawing a vivid parallel between celestial and earthly battles.

Milton’s extensive classical influences also bolster the poem’s impact. He models the poem’s structure on Homeric and Virgilian epics, bringing the heroic verse tradition to English literature. Renaissance ideas of “imitatio,” or creative imitation, informed Milton’s approach. Rather than simply copying Genesis, he reinterprets and surpasses earlier texts through a synthesis of sources, blending Christian and classical literature into an innovative whole.

The poem’s success was immediate and sustained. Upon its 1667 publication, “Paradise Lost” quickly sold its initial print run of 1,300 copies and went through several additional editions. Milton’s reputation as a controversial, politically involved writer heightened readers’ interest. The poem’s complex theology and political undertones sparked discussion and analysis.

Its fame surged again during the Romantic period, when poets such as Blake, Shelley, and Byron revived interest in Milton’s Satan. Blake especially saw Milton as a “true Poet” embracing the devilish perspective in his works. This era redefined Satan as a Byronic hero—a defiant, eloquent, and tragic figure—adding layers of cultural meaning that have kept “Paradise Lost” relevant through succeeding generations.

- Milton’s “Paradise Lost” is a creative expansion and reinterpretation, not a mere retelling of Genesis.

- Satan is a complex, central character, crafted as a rebellious antihero, differing from biblical texts.

- The poem blends Christian theology with classical epic traditions and Renaissance literary theory.

- Political context of the English Civil War deeply influences its themes and allegory.

- Initial publication saw strong contemporary interest, with lasting influence renewed in the Romantic era.

Why Was John Milton’s Epic Poem Paradise Lost So Wildly and Historically Successful If It Was Just a Retelling of the Story of Genesis?

The short answer is this: Paradise Lost isn’t just a retelling of Genesis; it’s a bold, richly layered expansion that blends theology, politics, and classical influences into an epic tale with unforgettable characters — especially Satan — portrayed in a way that was revolutionary for its time. So, if you think Milton simply copied the Bible’s Book of Genesis and expected readers to be awestruck, think again!

Let’s unpack why this 17th-century poem grabbed the world by the collar and never let go.

It’s Not Just a Bible Rehash — Milton Rewrote the Rules

You might think, “Genesis? Been there, done that.” But Milton’s Paradise Lost is less a copy-and-paste job and more like an imaginative remix with a fresh beat. The epic stretches beyond Genesis’s scope. It combines elements from the Book of Revelation and classical texts like Homer and Virgil.

Picture this: Genesis tells the straightforward tale of Creation and the Fall of Man. Milton takes that skeleton and injects wings, fire, and some serious swagger. The poem expands the narrative, making it a cosmic saga about the eternal battle between good and evil.

This isn’t a Bible study—it’s a sprawling epic war with angels, devils, and humans caught in a spiritual crossfire.

Enter Satan: The Antihero Who Stole the Show

One of the biggest reasons Paradise Lost is a literary legend is Milton’s masterstroke of personalizing Satan. Unlike the Bible—which barely mentions Satan in Genesis, focusing instead on the Serpent—Milton crafts Satan into a multi-dimensional character. He isn’t some one-dimensional villain. He’s almost heroic in his rebellion, delivering lines like “Better to reign in Hell than serve in Heaven.”

Milton invents an entire backstory for Satan, showing him as a fallen angel who rallies his forces after a galactic Angelic War lost to God. He braves the Abyss, uses sharp rhetoric to mobilize his rebel angels, and even parallels Christ’s resistance in the desert. No wonder readers kept coming back: Satan’s charisma makes the story pulse with tension and complexity.

Think of it as the original villain origin story—without it, Paradise Lost would just be a dry recounting of a biblical chapter.

God and the Son: Far From One-Dimensional Figures

Milton’s depictions aren’t straightforward either. God isn’t a distant, purely benevolent monarch here. Instead, He’s omnipotent and omniscient, with the fall of man woven into His grand plan. Meanwhile, the Son of God, who plays a key role, is portrayed according to Milton’s own theological stance—one of “subordinatism,” meaning the Son is secondary to the Father.

This theologically nuanced portrayal invites readers to grapple with profound ideas rather than just accept a simple moral tale.

Milton’s Personal Story and Historical Context Imprint The Poem

Milton wasn’t just a poet cocooned in ivory towers. He lived through upheaval: the English Civil War, political turmoil, and personal tragedy. He began writing Paradise Lost the same year Oliver Cromwell died, and shortly after losing his second wife and infant daughter. By then, Milton was blind and dictated the entire epic through assistants.

That intense backdrop informs his writing. The rebellious angels mirror the political rebellions of his time—the struggles between monarchy and parliament, Puritans and Cavaliers. Milton’s politics aren’t hidden; he wrote some fiery pamphlets advocating for the execution of Charles I. He was not a mere Parliamentarian sympathizer but an agitator.

When Satan invents cannons in Book VI, it’s no random fantasy. These “devilish Engines” pull from recent memories of war. Readers at the time would recognize the parallels. Milton makes Genesis feel urgent and contemporary, bridging ancient myth and immediate reality.

The Renaissance Spirit: Imitation as Creation, Not Copying

Let’s bust a myth: Milton didn’t simply copy Genesis. The Renaissance era championed the idea of imitatio, a concept where writers drew inspiration from prior works and improved or transformed them.

Think of poets as bees, collecting nectar from various flowers (classical texts, religious writings) and making unique honey (original poetry). Milton’s skill was weaving these diverse sources into a new masterpiece, showing creative brilliance—not plagiarism.

This is why classical epic styles echo through Paradise Lost. Milton took Homer and Virgil’s heroic verse as his blueprint, striving to legitimize English poetry on the world stage. The poem is both a literary and cultural milestone.

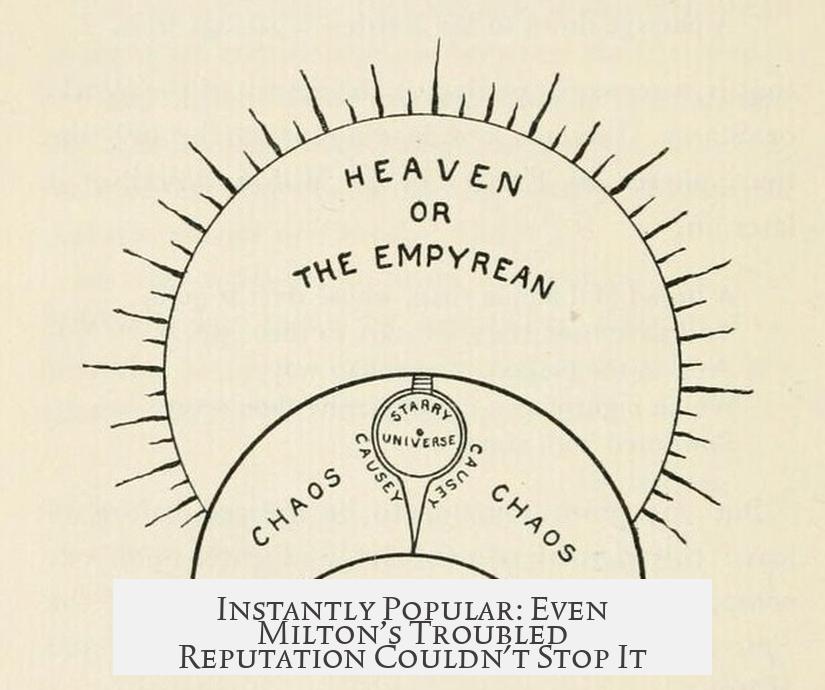

Instantly Popular: Even Milton’s Troubled Reputation Couldn’t Stop It

Upon publication in October 1667, Paradise Lost found eager readers. The first print run of 1,300 copies sold quickly, followed by three more impressions in short order. Milton wasn’t just any poet—he was a notorious anti-monarchist firebrand. That flair added to the poem’s allure.

His public image invited curiosity, and combined with the poem’s compelling exploration of themes like free will, rebellion, and divine justice, readers couldn’t put it down.

Romantic Revival: Satan as the Tragic Antihero

Move forward a century or two. The Romantic poets—Blake, Shelley, Byron—rescued Paradise Lost from dusty shelves. They adored Milton’s Satan, celebrating him as a tragic, sympathetic figure. William Blake famously said Milton wrote “in fetters” about angels and God but was “at liberty” when writing about devils.

This cult admiration transformed Milton’s poem into a foundational work for the Byronic hero concept: the aloof, rebellious, brooding character who defies norms but captivates hearts.

Is Paradise Lost Just a Bible Retelling? Think Again.

Here’s a question to ponder: When does a story stop retelling and start creating? Milton’s Paradise Lost is the perfect example showing this boundary is blurred and fluid.

- Makes Satan a complex protagonist.

- Intertwines theology with politics and personal grief.

- Incorporates contemporary elements like cannon warfare.

- Adopts classical poetic structures with theological innovation.

- Challenges readers to rethink familiar religious narratives.

For readers and critics alike, Paradise Lost wasn’t just a poem: it was a bold reinvention, an epic debate, and a cultural touchstone that reflected Milton’s world and continues to challenge ours.

Takeaways and Practical Tips for Readers Today

If you’re approaching Paradise Lost for the first time, here are some tips:

- Don’t expect a straightforward Bible tale. Embrace the complex characters and grand themes.

- Look at historical context. Knowing Milton’s political background and personal tragedies deepens appreciation.

- Notice how Milton blends influences. The poem connects Christian theology with classical epic style in a unique way.

- Pay attention to Satan’s speeches. They reveal the poem’s moral ambiguity and rhetorical brilliance.

- Enjoy the narrative’s freshness. Whether Satan inventing cannons or heavenly battles, Milton makes ancient stories resonate with contemporary urgency.

Milton’s genius was transforming a religious text into a literary epic that sparks questions about power, obedience, freedom, and identity. No wonder Paradise Lost has been wildly and historically successful for centuries. It keeps reinventing itself in readers’ minds.

Summary Table: Differences Between Genesis and Paradise Lost

| Aspect | Genesis | Paradise Lost |

|---|---|---|

| Scope | Creation and Fall of Man | Angelic War, Creation, Human Fall, and Cosmic Conflict |

| Main Characters | God, Adam, Eve, Serpent (unnamed) | God, Son, Satan (fully developed), Angels, Humans |

| Theme | Origin of humanity and sin | Free will, rebellion, justice, tragedy |

| Characterization of Satan | Serpent (ambiguous) | Complex antihero with motives and eloquence |

| Historical Context | Ancient Hebrew traditions | 17th-century England: civil war, politics, theology |

| Style | Religious text | Epic poetry with classical influences |

In conclusion, Paradise Lost is a towering achievement because it reimagines an old story in a new, thought-provoking light. It blends Milton’s personal sorrows, political struggles, and Renaissance ideals with biblical tradition and epic form. That mix gave readers something they’d never seen before: a timeless exploration of good and evil, rebellion and redemption, filled with nuance and dramatic flair.

Q1: How is Paradise Lost different from the biblical story of Genesis?

Milton’s poem expands on Genesis by adding new narratives and characters. It combines elements from Genesis, Revelation, and classical texts. It also includes a detailed portrayal of Satan, who is barely present in Genesis itself.

Q2: Why is Satan portrayed so prominently in Paradise Lost?

Milton creates Satan as a rebellious angel and gives him a dramatic role. This character is almost heroic and speaks some of the poem’s most memorable lines, shaping the poem’s deeper themes of rebellion and authority.

Q3: What contemporary issues influenced Milton’s writing of Paradise Lost?

Milton wrote after the English Civil War and reflected on political and religious conflicts. He used scenes like angelic battles armed with gunpowder to echo the warfare of his time, linking biblical events to current struggles.

Q4: How did Milton’s background affect the poem’s composition?

Milton lived through political upheaval and personal loss, including blindness and bereavement. His roles as a political writer and government employee informed the poem’s complex views on power, freedom, and divine justice.

Q5: What classical influences shaped Paradise Lost’s style?

Milton aimed to bring the heroic verse of Homer and Virgil to English poetry. He followed Renaissance ideas of imitation, drawing on classical works but transforming them to create something original within a Christian framework.

Q6: How was Paradise Lost received when it was first published?

The poem quickly gained readers after its 1667 release, with several printings. Milton’s known political stance as an opponent of monarchy attracted interest, helping establish the poem’s historic success beyond a simple biblical retelling.