The names of Santa’s reindeer were introduced by the 1823 anonymous poem commonly known as “A Visit from St. Nicholas,” often attributed to Clement Clarke Moore. This poem standardized the eight famous reindeer names: Dasher, Dancer, Prancer, Vixen, Comet, Cupid, Donder (later Donner), and Blitzen.

Prior to this poem, the image of Santa Claus with reindeer existed but was not clearly defined with specific names. In 1821, another poem titled Old Santeclaus with much delight mentioned reindeer pulling Santa’s sleigh. However, it did not provide the well-known names that Moore’s poem later introduced. This 1823 poem thus popularized and fixed the reindeer names used today.

Before flying reindeer became associated with Santa, the traditional depiction of St. Nicholas featured him riding a horse. In Dutch-American culture, he reportedly traveled in a horse-drawn wagon that could move both on the ground and on treetops. Similarly, European Dutch traditions showed St. Nicholas riding a horse across rooftops. The switch from horse to flying reindeer happened shortly before the poem appeared, marking a significant evolution in Santa iconography.

The 1823 poem did more than just name the reindeer. It introduced the idea that Santa’s reindeer could fly. The text uses the verb “flew” to describe their rising from the ground to the rooftop, suggesting motion through the air. The number eight also became fixed here, though earlier concepts hinted at this number.

| Key Development | Details |

|---|---|

| Earlier reindeer mention | 1821 poem “Old Santeclaus with much delight” depicted Santa with reindeer, no fixed names |

| Standardizing names | 1823 poem first introduced the eight reindeer names now famous worldwide |

| Before reindeer | St Nicholas depicted with a horse in Dutch and European traditions |

| Flying reindeer concept | 1823 poem used “flew”; popularized the idea of flying reindeer |

Authorship of the 1823 poem remains uncertain. It was first published anonymously in the New York newspaper The Troy Sentinel. The publication’s introduction notes the author was unknown at the time. Clement Clarke Moore first claimed to have written the poem in the 1840s, about twenty years after its publication.

This claim has faced skepticism. Some view it as opportunistic since the poem’s popularity made authorship prestigious. However, Moore’s claim also carries some credibility because falsely claiming such a well-known poem might have exposed him to public disproof. No other writer has gained recognition as the poem’s author.

Scholars examining American Christmas iconography, such as Penne Restad, highlight Moore’s role in the poem’s popularity but caution against unquestioning acceptance of his authorship. Restad’s research balances admiration for Moore with awareness of unresolved authorship debates.

In summary, the poem often attributed to Clement Clarke Moore is the source of the eight names of Santa’s reindeer. It reshaped Santa Claus imagery by introducing flying reindeer with distinct names. However, the exact authorship remains somewhat unclear due to anonymous initial publication and Moore’s delayed claim.

- The famous eight reindeer names originate from the 1823 poem “A Visit from St. Nicholas.”

- Earlier references to Santa with reindeer existed but lacked named reindeer.

- St. Nicholas traditionally rode a horse before the reindeer concept emerged.

- The poem popularized the idea of flying reindeer.

- Authorship is uncertain; Clement Clarke Moore claimed it two decades later.

- Some experts remain skeptical about Moore’s full authorship.

Were the names of Santa’s Reindeer created by Clement Clarke Moore?

Yes, the beloved names of Santa’s reindeer were introduced by the 1823 anonymous poem now famously known as A Visit from St. Nicholas, which is often attributed—but not conclusively—to Clement Clarke Moore. But let’s unwrap the story behind those jingling names before we deck the halls with certainty.

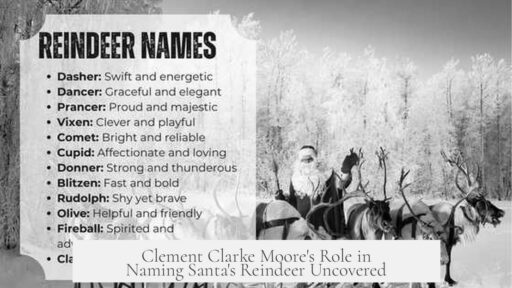

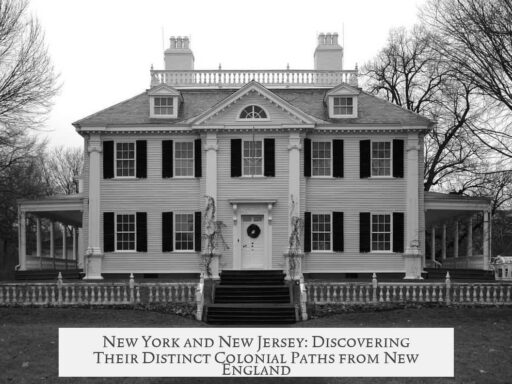

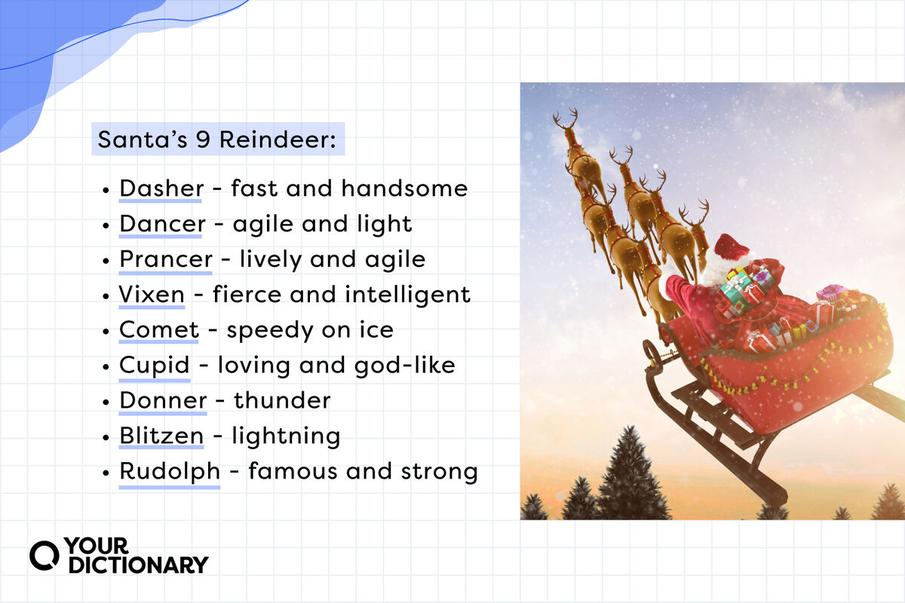

Most people picture Dasher, Dancer, Prancer, Vixen, Comet, Cupid, Donder (or Donner), and Blitzen as timeless icons of holiday lore. But these eight bold reindeer didn’t prance into cultural consciousness on their own; they were gifted to the world through poetry.

Interestingly, the poem appeared anonymously in The Troy Sentinel on December 23, 1823. The editors introduced it with warm words about “that unwearied patron of children,” Santa Claus himself, yet the author’s identity was a mystery. Only years later, Clement Clarke Moore stepped forward to claim credit, sparking debate that still jingles today.

From Horses to Reindeer: Santa’s Journey

Before Moore’s poem—or its anonymous incarnation—Santa wasn’t always flying through the wintry sky with reindeer. The Dutch and European traditions featured St Nicholas riding a horse that could scamper both on rooftops and treetops. In fact, early American Dutch customs had him driving a wagon pulled by this magical horse, a vision drastically different from eight airborne hoofbeats.

The shift to reindeer happened around 1821, when another New York poem called Old Santeclaus with much delight depicted Santa with reindeer for the first time. That poem didn’t name or number the reindeer, but it marked a pivotal moment introducing the concept. Just two years later, the 1823 poem standardized the eight reindeer, assigning them names and personalities that have lasted nearly two centuries.

Reindeer Names: Flying into Tradition

Did Santa’s reindeer always fly? The 1823 poem uses the word “flew” to describe their movement, suggesting the magical airborne journey. This imagery might have been new or borrowed from other flights of fancy, but the poem cemented the idea. It also gave us those memorable names we love to chant during December gatherings.

Here’s how those names first appeared in poetic glory:

Now, Dasher! now, Dancer! now, Prancer, and Vixen! On, Comet! on, Cupid! on, Donder and Blitzen! To the top of the porch! to the top of the wall! Now dash away! dash away! dash away all!

Knowing these names emerged from a creative work—not from ancient lore—makes us wonder: what inspired these particular syllables? Some suggest Moore or the anonymous poet borrowed on German and Dutch words or sounds to craft names that sounded energetic and festive. For instance, “Donder” is akin to the Dutch word for thunder.

Who Really Penned This Yuletide Classic?

The authorship story is as twisty as tinsel on a tree. When the poem first appeared in 1823, it arrived anonymously. No author signed under the glowing moonlight. It took more than a decade before Clement Clarke Moore publicly claimed to have written it.

Some historians find this claim a bit convenient—almost as if Moore saw how wildly popular the poem was, and then waved his hand to say, “That was me!” Yet, others argue that claiming authorship for such a widely loved piece carried risks. If he’d lied, someone might have called him out back then. So, skeptics and supporters alike remain locked in a friendly standoff.

Critically, scholarly works like Penne Restad’s Christmas in America. A History laud Moore’s role but don’t fully address doubts about authorship. Restad’s admiration for Moore and Washington Irving sometimes overlooks alternative possibilities. Despite speculation, no competing author has emerged with stronger proof.

Why Does Knowing This Matter?

Understanding the origins of Santa’s reindeer names helps us appreciate how cultural icons evolve. It reminds us that traditions we consider eternal often have specific, sometimes surprising beginnings. The story of Santa’s reindeer names is a perfect example of how literature shapes holidays—and how a poem can go from an anonymous print to a cornerstone of Christmas mythology.

If you’re looking for holiday trivia to impress guests, try this: The names we cherish were created, popularized, and standardized in an 1823 poem—most likely by Clement Clarke Moore—but initially published anonymously. Before that, Santa was a horse rider, not a reindeer wrangler, and the magic of flying reindeer was a poetic innovation that stuck.

How to Share This Tale at Your Next Holiday Dinner

- Start with a question: “Did you know Santa’s reindeer names are only about 200 years old?”

- Mention the 1823 poem: Explain how it introduced the eight names and flying reindeer.

- Drop the authorship mystery: Share that Clement Clarke Moore, a scholar and professor, claimed authorship years later, but no one is 100% sure.

- Compare old traditions: Note that Santa used to ride a magical horse in Dutch traditions.

- Highlight the fun: Suggest imagining a Santa who trades his reindeer for a horse and a wagon next Christmas.

This curious mix of fact, folklore, and poetic creativity enriches our enjoyment of the holiday season. It shows that myths adapt, and sometimes the best traditions begin with a playful poem.

So, next time you call out “On, Dasher! On, Dancer!”—you’ll know exactly where those jingle-hoof names first took flight.

Did Clement Clarke Moore create the names of Santa’s reindeer?

The names of Santa’s reindeer first appeared in the 1823 poem commonly known as “A Visit from St. Nicholas.” While Moore is often credited, the poem was originally published anonymously. The names were introduced through this poem.

Were Santa’s reindeer mentioned before Moore’s poem?

Yes, an earlier 1821 poem also showed Santa with reindeer. However, that poem did not list the familiar eight names. Moore’s poem standardized these names and made them widely known.

Was Santa always associated with reindeer before the poem?

Before the 1820s, Santa or St Nicholas was commonly depicted with a horse, not reindeer. In Dutch traditions, he rode a horse that could travel on rooftops. The shift to reindeer came shortly before the 1823 poem.

Did Clement Clarke Moore immediately claim authorship of the poem?

The poem was published anonymously at first. Moore only claimed authorship decades later, around the 1840s. Some scholars doubt this claim, as there is little solid evidence linking him to the work originally.

How did the poem influence Santa’s reindeer flying concept?

The poem used the word “flew” to describe the reindeer’s journey. While the idea of flying reindeer was not widely established before, the poem popularized it, strengthening the image of Santa’s airborne sleigh team.