Denda’s helmet is not purposely designed to look phallic. There is no solid evidence to suggest the helmet’s shape intentionally evokes a phallic symbol. Greek cultural norms and artistic traditions strongly argue against such symbolism in armor, especially helmets worn into battle.

Greek art and statues emphasize the male ideal with modesty, typically showing small, flaccid genitalia. Large, erect phallic symbols were culturally linked to poor self-control and associated with low-born men or mythological creatures like satyrs. A respected Greek warrior wearing a helmet resembling an erect penis would contradict these values and is highly implausible.

Moreover, Greek armor decorations and shield blazons frequently use positive symbolism but omit phallic imagery. There is no known example of a Greek shield or helmet intentionally portraying a penis, despite the broader symbolic use of the image in other contexts.

The helmet in question resembles a Corinthian style, which was prominent around the 8th to 5th centuries BC. This helmet style evolved for functionality: it fully enclosed the skull, provided comfort, and was made from hammered bronze. The peak of the helmet’s faceplate aligns with the crest base, not to mimic glans.

Notably, the helmet shape more resembles a circumcised penis, yet Greeks did not practice circumcision, further undermining deliberate phallic design theories.

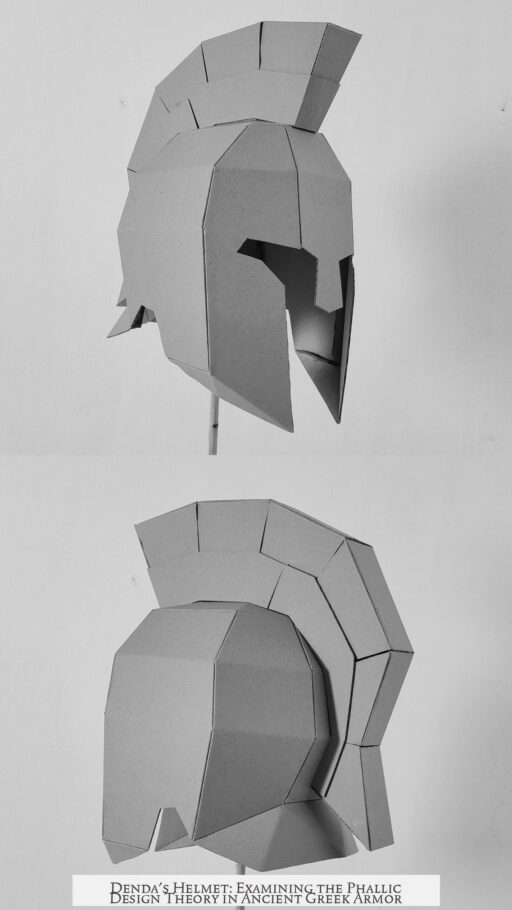

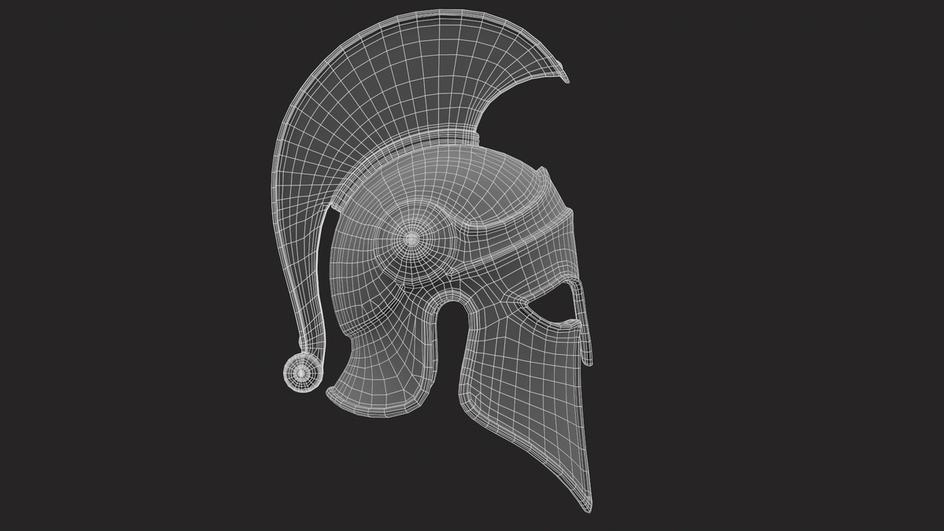

Horsehair crests typically topped these helmets, altering the visual impression. With the crest, the helmet loses any superficial phallic resemblance, emphasizing its practical design over symbolic shape.

- Greek cultural norms disfavored exaggerated phallic imagery in respected portrayals.

- No evidence supports phallic symbolism in Greek helmets or shield designs.

- Corinthian helmets focused on protection and fit, not symbolic shapes.

- The helmet’s shape contradicts Greek practices like circumcision.

- Crests changed the helmet’s silhouette, reducing any phallic impression.

Is Denda’s Helmet Purposely Designed to Look Phallic? A Closer Look at Ancient Greek Armor

If you’ve ever glanced at the ancient helmet found at Denda and wondered, “Is this helmet purposely designed to look phallic?” the direct answer is: Highly unlikely.

Sure, on first glance, the shape might strike some as… suggestive. The pointed, rounded front of the Corinthian-style helmet bears a vague resemblance to certain anatomical features. But before we leap to conclusions or imagine an ancient Greek warrior strutting into battle dressed as a walking innuendo, let’s unpack the history, culture, and craftsmanship behind this iconic piece of armor.

So—why does this helmet shape evoke such thoughts, and is there anything substantial backing a phallic design? Spoiler: no.

Understanding the Helmet’s Origins and Design

The helmet in question is a descendant of the classic Corinthian helmet, a staple of Greek warfare from the 8th century BC onward. It evolved from earlier, less practical helmets inspired by Assyrian designs. The key innovation here was full head coverage, combining protection with a snug fit, all hammered from a single bronze sheet. This wasn’t about symbolism first—it was about survival.

This helmet enclosed the entire head and face with narrow eye slits and a slight peak around the nose, designed for maximum defense. The peak naturally came to a point where it met the helmet’s horsehair crest—adding height and grandeur for warriors, but also disguising sharp metal edges and potentially deterring enemy strikes.

When that horsehair crest is attached, the helmet looks far less like anything in the genital department. Instead, it appears more like a full-bodied war mask than a risqué sculpture.

What Does Greek Culture Tell Us About This?

Ancient Greeks had clear attitudes about anatomy and depictions in art. Interestingly, their art frequently showed men with small, flaccid genitalia. Contrary to modern assumptions, large genitals were not admired—they symbolized poor self-control and barbarism. Depictions of “big dicks” were reserved for low-born men, satyrs, and other figures society looked down upon.

Given these cultural norms, it would be counterintuitive for a Greek citizen—and especially a warrior of status—to don a helmet deliberately designed to mimic a large phallus. That would be like attending a serious military campaign in a cheeky costume, which seems inconsistent with Greek values of dignity and honor in warfare.

Vase Paintings and Shield Designs Offer No Clues

If anyone was going to get bold and adorn their equipment with phallic symbolism, one might think it would show up on shields or even helmets worn for public spectacle. But historical vase paintings, which richly detail Greek warfare and motifs, rarely feature phallic designs as armor decorations. Shields had an array of boasts—heroes, animals, mythological symbols—but no phalluses.

This absence suggests the symbolism was likely kept out of serious martial contexts. It was perhaps part of private, comedic, or ritual art, but not battle gear polished for the battlefield.

The Curious Case of Circumcision and Helmet Shape

Here’s a fascinating detail: some have noted that if the helmet looks vaguely like a penis, it resembles a circumcised one. The problem? Ancient Greeks did not practice circumcision. If there was purposeful phallic symbolism, wouldn’t it align with the local cultural and anatomical reality? This mismatch further weakens any theory that the helmet’s shape was a deliberate phallic statement.

Was the Helmet Design an Accidental Phallus?

Sometimes, shapes and forms evolve for functional reasons and then gain quirky interpretations much later. The Corinthian helmet’s design prioritized protection, vision, and comfort. The rounded front is the natural shape formed by the metal sheet hammered over the face, which converges at the nose—this naturally creates a pointed contour. When later helmets like Attic or Boeotian forms came around, these features disappeared, reflecting changing styles rather than symbolic shifts.

In other words, if the helmet resembles an erect penis, it’s probably coincidence—function over form prevailed.

The Bigger Picture: Helmets as Practical Gear, Not Phallic Statements

War and armor were deadly serious endeavors for the Greeks. Their soldiers (hoplites) needed to trust their gear implicitly. Comfort and protection were paramount; any shape that impeded vision or movement would be rejected. Designing armor to look phallic, and perhaps distract or deal embarrassment, seems entirely contrary to practical battlefield needs.

Plus, consider the social circles and politics: A helmet designed to look like male genitalia might spur snickers or worse among comrades and enemies alike. The gains in morale? Zero. The risks? High. Greek hoplites preferred a helmet that inspired fear, respect, and safety.

Conclusion: Function, Culture, and Context Triumph Over Speculation

Is Denda’s helmet purposely designed to look phallic? The evidence says no. It’s neither supported by contemporary sources nor consistent with Greek cultural norms. The helmet is a product of practical innovation combined with aesthetic choices that prioritized protection and style appropriate to its time.

Next time someone spots the Denda helmet and chuckles or raises an eyebrow, you can confidently share the rich history behind it. Ancient Greek helmets weren’t secret adult symbols—they were war machines crafted for survival, not shock value.

And if you want to dig deeper, take a look at how the horsehair crest changes the helmet’s silhouette—it’s a great reminder that context matters when interpreting ancient artifacts.

Curious? Feel free to check out this photo with the crest attached and see the difference for yourself.

Who knew ancient warfare could spark such lively debates with a dash of unintended humor?

Is there any historical evidence that Denda’s helmet was designed to look phallic?

No direct evidence confirms that the helmet was meant to look phallic. Greek art and culture rarely showed large genitalia positively, especially not in noble or military contexts.

Why is it unlikely that Greek helmets had phallic symbolism?

Greek society viewed large genitalia negatively, associating it with poor self-control and lower status. Helmets and armor had no known phallic decorations either.

Could the helmet’s shape be an intentional symbol despite Greek norms?

The helmet resembles a circumcised penis, but Greeks did not practice circumcision. This inconsistency suggests the shape was unintentional.

How does helmet functionality affect its shape?

The design evolved for protection and comfort, made from hammered bronze to fully cover the head. Practical needs likely shaped its form more than symbolism.

Does attaching a crest change the helmet’s appearance?

Yes, a horsehair crest covers the top and curbs any phallic resemblance, indicating the overall look wasn’t meant to be suggestive.