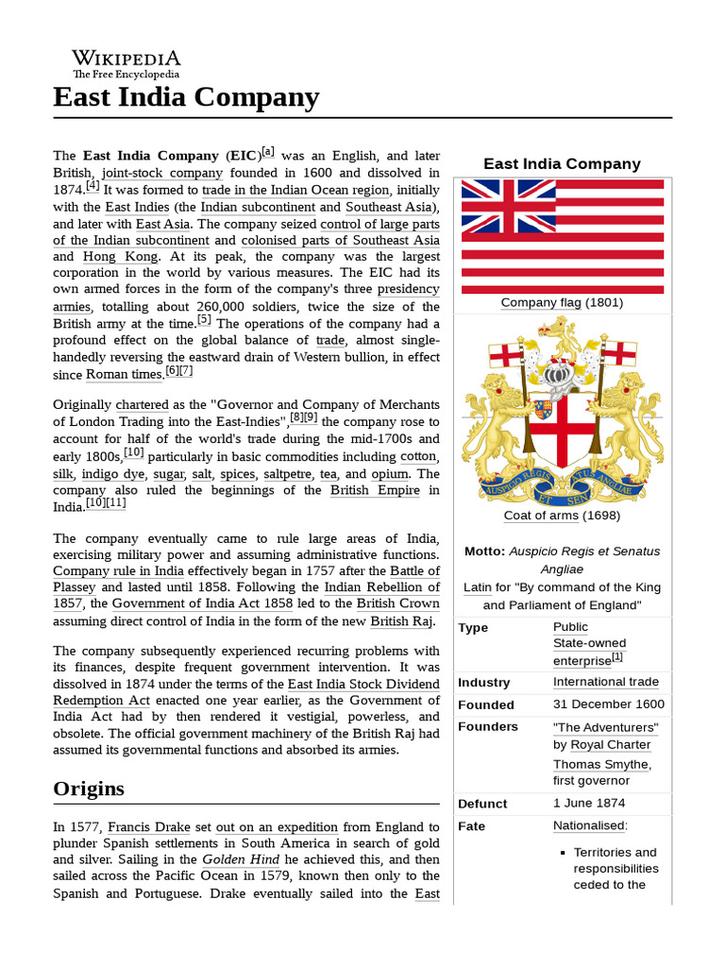

At its height, the East India Company (EIC) commanded immense wealth and power, controlling vast Indian territories and exercising military authority. It held extralegal privileges such as trade monopolies and legal exemptions, granted by imperial charters and local rulers. Its closest comparable entity is the Dutch East India Company (VOC), which shared similar features in wealth, military influence, and semi-sovereign status.

The East India Company began as a commercial trading enterprise in 1600. Initially, its wealth came from monopolistic trade in exclusive goods. Unlike the VOC, which secured near-monopolies on rare spices from the Indies to amass extraordinary riches, the EIC’s early profits were more modest due to a cautious business model favoring risk-sharing with wealthy merchants.

By the 18th century, the EIC’s role shifted dramatically. It moved beyond commerce toward territorial control in India. The Company established military dominance and started collecting land taxes from native tenant farmers. Over time, tax revenue significantly outstripped commercial gains, becoming the core of the Company’s wealth. This shift transformed the EIC from a trade monopoly to a quasi-sovereign power with armies and administrative functions in large parts of India.

Despite this formidable power, the EIC remained subject to British state authority. The government retained ultimate control by imposing taxes on imports, limiting charter durations, and extracting substantial loans. The Company’s autonomy ended after the Indian Rebellion of 1857, when its armies and administered lands were absorbed directly into British Government rule.

The EIC enjoyed several extralegal privileges enabling its dominance. It secured royal monopolies granting exclusive rights to trade goods from Asian territories to England. The Company also obtained exemptions from local laws and customs duties in regions controlled or influenced by it. A notable example is the 1717 grant from the Mughal emperor, which exempted EIC operations from many Indian legal restrictions.

Nevertheless, these privileges were not absolute. The British Crown and Parliament held the upper hand. By controlling the renewal of Company charters, they could regulate or rescind these rights. They used the threat of non-renewal and financial demands to keep the EIC under political supervision. The Company’s dependence on the Crown’s goodwill ensured it never became an independent sovereign power despite its military and fiscal authority.

| Aspect | Details |

|---|---|

| Trade Monopolies | Exclusive rights to import Asian goods; legal exemptions in host territories. |

| Territorial Control | Military governance over large regions of India; land tax collection as main revenue. |

| Subordination | Under British Crown’s authority; charter renewals and taxation regulated Company power. |

The closest analogue to the East India Company is the Dutch East India Company (VOC). Founded around the same time as the EIC, the VOC combined commercial monopoly rights with military capabilities and territorial control, acquiring immense wealth through trade in spices and colonization. Both companies demonstrated a blend of private business enterprise and imperial power.

The East India Company’s model foreshadows modern proxy relationships between business and state. Like the Virginia Company, which established Jamestown under Crown charter, these companies operated semi-autonomously with government backing. Their charters allowed self-governance, military action, and economic exploitation akin to mini-states under overarching imperial sovereignty.

Today, no direct equivalent exists because sovereign states have replaced such mercantile empires. However, multinational corporations operating in unstable regions with private security forces and significant political influence echo elements of the EIC’s power dynamics. These companies do not hold formal sovereignty but can impact local governance and economies profoundly.

- The East India Company’s ultimate wealth came from tax revenue on Indian territories, surpassing commercial trade profits.

- It held extralegal privileges including trade monopolies and exemptions from local laws, sanctioned by imperial and royal charters.

- British state authority constrained the Company through charter controls, taxes, and political oversight.

- The Dutch East India Company is the closest historical analogue, combining trade, military force, and territorial administration.

- Chartered companies like the EIC acted as proto-colonial government proxies before direct state colonialism became dominant.

- Modern multinational corporations share influence features but lack formal sovereignty or military power like the EIC.

At Its Height: The Wealth and Power of the East India Company Explored

The East India Company (EIC) was extraordinarily wealthy and powerful, wielding influence well beyond a typical business, with extralegal privileges that let it operate like a mini-empire—yet it ultimately answered to the British government. Curious how a company could almost run a country? Let’s dive into its fascinating story, uncover what made it tick, and consider what modern entities come close to matching its blend of commerce and sovereignty.

How Wealthy and Powerful Was the East India Company at Its Peak?

Imagine a company that not only traded goods but also controlled armies, collected taxes from millions, and managed vast territories. That was the EIC by the 18th century. Initially, it made money through trade—especially spices, textiles, and tea—operating factories and monopolizing imports. But here’s a twist: unlike its Dutch rival, the VOC (Dutch East India Company), which focused heavily on commercial profits and spices, the EIC gradually shifted its priorities.

By the mid-to-late 1700s, the EIC had transitioned from just trading to ruling. It gained military control over large Indian territories and started collecting land taxes from native farmers. This tax farming became its main source of wealth, outstripping profits from trade. The commercial hustle was overshadowed by the power to amass wealth through direct governance. Call it early corporate mega-landlord status.

To put that into perspective, the EIC’s tax income funded its armies and administration, sustaining a private government ruling millions of people. Its influence wasn’t just economic but political and military. Yet, despite this enormous might, it was still not the ultimate authority. The company’s vast powers came from charters granted by the British Crown, and after the Indian Rebellion of 1857, the British government reclaimed control, dissolving the company altogether.

Did the East India Company Enjoy Any Extralegal Privileges?

Absolutely. The EIC’s privileges went way beyond simple business contracts. Early on, it secured exclusive trading rights—monopolies—shielded by royal charters and diplomatic deals. For instance, in 1717, the Mughal emperor granted the EIC exemptions from local laws and taxes in its Indian trading posts. This quasi-legal autonomy allowed the company to bypass local controls and act with almost sovereign authority in many respects.

But it’s a two-way street. While it enjoyed these privileges, the EIC’s charters also left it vulnerable to British governmental oversight and financial demands. The Crown could impose taxes on its imports and limit the period of the company’s monopoly via the duration of charters. Later, the British government even extorted loans from the company in exchange for political favors and continued support. So, the EIC walked a tightrope, balancing immense autonomy with state subjugation.

The Closest Modern Analogue—Is There One?

At first glance, trading corporations today seem miles apart from an entity that had its own armies and ruled territories. But the EIC’s structure resembles precursors to modern hybrid political-business relationships. Think about it: companies today don’t run armies (at least, not openly!), but they do shape global politics through economic power.

The most accurate historical analogue is probably the Dutch East India Company (VOC). Both had similar models—state-chartered monopolies with military power, territorial control, and massive wealth. They pioneered what became colonial capitalism.

On the modern front, there’s no direct equivalent, but some comparisons come to mind: multinational corporations influencing nations through economic leverage, or private military contractors with significant sway in conflict zones. The early 1600s’ charters for companies like the Virginia Company, which founded Jamestown, echo today’s complex state-private partnerships. These companies enjoyed semi-governmental powers—a blending rarely seen now outside government entities themselves.

Lessons from a Company That Was Almost a State

“The English East India Company was a pioneering — and sometimes troubling — experiment in how commerce and sovereignty could intertwine.”

Its wealth was staggering for its time, fueled by trade monopolies and the enormous tax revenues from controlling Indian lands. That revenue funded its military might, enforcing its rule and expanding territories. The company wasn’t just a business; it was a proto-state actor shaping history.

Yet its lifecycle reminds us of crucial limits: despite power, it answered to the British government, which could—and eventually did—reclaim authority. This checks-and-balances system kept the company’s independence in check, preventing it from becoming a fully independent state.

What About the Impact and Ethical Questions?

While the numbers and power are impressive, it’s essential to recall the impact on millions of Indians. The EIC’s tax farming caused widespread hardship, and its military campaigns reshaped entire societies. This convergence of profit and governance created conflicts of interest that still fuel debates about corporate power and responsibility.

Does our modern world face similar dilemmas when corporations wield outsized influence over political or social life? Companies today may not tax or govern, but when their economic clout affects national policies, the questions become similar. How much power should any enterprise wield over people’s lives?

How Can We Understand the East India Company’s Legacy Today?

For those fascinated by history or looking to understand the roots of global economic power, the EIC offers a lens onto colonial capitalism’s early model. It shows how commerce and empire-building were once inseparably linked.

- Practical takeaway: When large corporations operate across borders today, monitoring their political influence is vital to avoid unchecked dominance like the EIC wielded.

- Comparison tip: Look at the VOC—the “sister company” with similar scale and role—to understand trade-monopoly-driven colonialism.

- Reflection: Think about the blend of government and private power—early state-private alliances—that shaped modern capitalism.

Final Thoughts

The East India Company was a colossal entity that blurred lines between business and statecraft. It amassed unimaginable wealth through trade and taxes, held extralegal privileges granting semi-sovereign status, but ultimately bowed to the British Crown. Its model foreshadowed not just colonialism but complex state-commercial interactions still relevant today.

So, next time you sip tea or pick up a global brand, remember: your simple cup has echoes of a company that once ruled territories like a miniature empire—with riches rivaling many nations.