Jews have been persecuted by many groups, fervently and frequently, due to a complex combination of historical, religious, economic, and social factors. These forces intersect in ways that repeatedly placed Jews in vulnerable minority positions near powerful empires, while their distinct identity and economic roles often provoked resentment and suspicion.

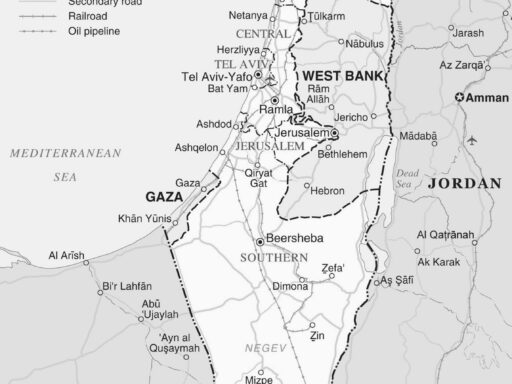

Their historical geographic placement, surrounded by dominant empires, exposed them to repeated conquest. From ancient Egyptian and Babylonian rule through Persian, Greek, Roman, and later Islamic domination, Jews lived as a minor civilization amid great powers. Their monotheistic religion and cultural distinctiveness frequently clashed with the religious and political norms of ruling authorities, resulting in tensions and uprisings that sometimes triggered brutal repression.

During the medieval and modern periods in Europe, persecution intensified with new layers. Jews often occupied economic roles many Christians shunned, such as moneylending, due to religious prohibitions on usury. This niche created economic success for some Jews, which in turn led to envy and hostility. Social restrictions barred Jews from owning land or joining many professions, concentrating them in finance and trade. This visibility combined with economic success fueled antisemitic conspiracy theories, including fabricated lies about controlling global finance.

Religious prejudice contributed strongly to persecution. Christian doctrine, especially influenced by the Gospel of John, cast Jews as hostile to Jesus and blamed them for his death. These theological narratives justified centuries of discrimination and violence. Jewish rejection of Christian beliefs about Jesus’ divinity further alienated them. The Catholic Church officially repudiated collective blame only in the 20th century with Vatican II’s Nostra Aetate, but the damaging legacy persisted for centuries.

Jews’ distinct customs, language, and religion set them apart visibly in largely homogenous societies, making integration difficult. Their cultural cohesion preserved identity but reinforced otherness. Rumors and myths, like blood libel and host desecration, flowed from fear and ignorance. Social alienation made Jews easy scapegoats for broader crises, such as during the Black Death or political upheavals like the pogroms in Russia.

- Economic envy and political manipulation: Jewish wealth was sometimes exploited by rulers who imprisoned or taxed Jewish bankers, as with the Oppenheimers in Vienna. Anti-Semitic laws sometimes served as tools for extortion or confiscation.

- Scapegoating during crises: Jews were blamed for wars, economic downturns, and diseases. Notable incidents, such as the Dreyfus Affair in France, exploited nationalist resentment toward Jewish minorities.

- Minority status and self-perpetuation: Being a minority with strong cultural boundaries intensified suspicion. Legal and social restrictions forced Jews into specific economic roles, maintaining a cycle of exclusion and vulnerability.

The persecution of Jews can be seen as a self-fulfilling prophecy. Repeated targeting and survival solidify their visible difference, which antisemites interpret as justification for hostility. Jewish cultural resilience, though a strength for survival, paradoxically reinforced perceptions of separateness.

In summary, the persistent persecution of Jews results from multiple overlapping reasons:

| Factor | Explanation |

|---|---|

| Geopolitical Vulnerability | Located among great empires, Jews faced repeated conquest and oppression without political power. |

| Religious Hostility | Christian doctrine long portrayed Jews as responsible for Jesus’ death, fostering hatred and institutional discrimination. |

| Distinct Cultural Identity | Unique customs and language set Jews apart, sparking fear and myths reinforcing antisemitism. |

| Economic Roles | Restrictions pushed Jews toward finance and trade, fields that generated resentment and stereotypes. |

| Scapegoating Mechanism | Jews were targeted as convenient culprits in social, economic, and political crises. |

| Legal and Social Segregation | Laws restricting residence, dress, and professions made Jews more visible and alienated. |

Their survival is linked to strong communal solidarity and adaptability. Despite enduring severe persecution, Jewish culture preserved endurance traditions, enabling eventual recovery and growth during periods of tolerance. This pattern of exclusion and perseverance has shaped modern Jewish identity and political activism.

- Jews’ position near dominant empires exposed them to repeated conquests and religious pressures.

- Christian theological narratives deeply influenced long-term antisemitism.

- Economic roles shaped by exclusion created envy and suspicion.

- Social and cultural distinctiveness fostered fear and myths leading to persecution.

- Jews were frequent scapegoats during social crises, magnifying hostility.

- Self-perpetuating cycles of persecution and survival entrenched Jewish minority status.

Why Have Jews Been Persecuted by So Many Groups, So Fervently, and So Frequently?

The short answer: Jews have faced persecution throughout history because of a complex mix of geographical vulnerability, religious opposition, economic roles, cultural distinctiveness, minority status, and disturbing myths that fueled fear and hatred. Let’s unpack this tangled web with clarity, detail, and a dash of wit.

So many factors collide in this story that any simple explanation would be a disservice. Think of it as an unfortunate recipe that has simmered for millennia, with each ingredient adding its own flavor of suspicion, resentment, and cruelty.

Living Next Door to Powerhouses: A Geopolitical Magnet for Trouble

Jews have often existed in what we might call the “geopolitical danger zone,” squeezed between mighty empires. From the Egyptians to Babylonians, Persians, Greeks, Romans, and eventually Muslim caliphates, each conqueror passed through Jewish lands with differing policies and tolerance levels.

This isn’t a glamorous setting. Imagine being a small boat caught in the wake of massive ocean liners, constantly pushed around. After Babylonian exile, the Persians allowed Jewish restoration (big relief!), but soon enough Greek Seleucids tried to crush Jewish religion, sparking the Maccabean revolt. Romans conquered Jerusalem and religious tensions exploded into revolts. The Jews’ strict monotheism, denial of Jesus as divine, and visible cultural uniqueness always set them apart, often in the worst ways.

Bottom line: A tiny community surrounded by empires prone to suspicion and conquest became an easy target often ruled—and ruled over—by outsiders who saw difference as danger.

The Medieval European Mix: Money, Myths, and Mistrust

If you thought emperors were tough, try living as a Jewish person in medieval Europe—a time when economic roles and religious tension brewed a perfect antisemitic storm.

Christian doctrine forbade usury (the lending of money with interest) for Christians, yet moneylending was necessary in growing medieval economies. Enter the Jews, who, excluded from land ownership and many trades, found niches in finance and banking. Yes, they often grew wealthy, which, let’s face it, can trigger envy—especially when poured over centuries of religious prejudice.

Humans love conspiracy and scapegoating. Enter myths like the infamous “Protocols of the Elders of Zion” (a fake document blaming Jews for world domination), and rumors of Jews poisoning wells or kidnapping children. These stories reflected fears of difference, not facts.

Religion was no innocent bystander either. Many Christians labeled Jews as “Christ-killers,” a painful stereotype reinforced by texts such as the Gospel of John which portrays Jews negatively with phrases like “sons of the devil.” These theological roots fueled hate for centuries, only officially repudiated by the Catholic Church in the 1960s. Meanwhile, Jews lived apart, spoke different languages, kept their customs, and were perceived as alien in mostly mono-ethnic states.

Religious Theology’s Shadows Over European Thought

It’s hard to overestimate how much Christian theology shaped attitudes that justified persecution. The Gospel of John, in particular, casts Jews in a harsh light that *literally* shaped medieval Europe’s mindset.

- It describes Jews plotting to kill Jesus (John 7:1).

- Disciples hiding in fear from Jewish communities (John 20:19).

- Calls Jews “children of the devil” (John 8:39-45).

For centuries, these interpretations reinforced official and popular hostility. Even Martin Luther, a key figure of the Reformation, expressed antisemitic views. Jewish communities bore the brunt of this religious condemnation with expulsions, forced conversions, and violence.

Minorities by Design: The Self-Perpetuating Circle

Since the destruction of the Second Temple in 70 CE, Jews have mostly lived as minorities outside their ancestral homeland. Minority status, especially when combined with visible cultural practice and distinct religious beliefs, often means social and economic challenges.

Restrictions barred Jews from owning land or joining many professions, pushing them into certain trades. Their cohesive communities fostered solidarity but also increased their “otherness” perception. And societies, suspicious of the unfamiliar, often responded with hostility.

The story becomes a vicious cycle: exclusion and persecution led to visible separateness (like ghettos or enforced dress codes), which invited more suspicion and persecution. Over time, this dynamic appeared a “self-fulfilling prophecy.” People reasoned, “The Jews have always been persecuted, so there must be a reason,” which sadly justifies further targeting.

Economic Motives: More Than Religion at Play

Let’s not ignore the green-eyed monster—jealousy of wealth—often intertwined with politics and prejudice.

There are juicy tales like that of the Oppenheimers, wealthy bankers in Vienna who were imprisoned and robbed by kings hungry for assets. The Dreyfus Affair in France paints a vivid picture of how Jewish success and outsider status stoked nationalist and racist fears.

Anti-Jewish measures often served as tools to extract bribes or confiscate property rather than genuinely solve societal issues. Propaganda magnified myths, making economic envy bleed into irrational hate.

The Self-Fulfilling Prophecy: Survival as Both Strength and Problem

Here’s the irony: the very resilience and perseverance of Jewish culture in the face of adversity not only preserved a vibrant identity but paradoxically invited further persecution. Because Jews endured and remained distinct, many saw this as evidence that Jews were “different” in suspicious ways—feeding the endless cycle of alienation and blame.

Throughout this sad history, Jewish survival has been nothing short of remarkable—rooted in solidarity, learning, and sometimes finding havens like Muslim Spain or later America. But survival alone sometimes spurred new accusations.

A Complex Tapestry: Why It’s Not Black and White

It’s tempting to want to reduce this long history into a single cause. But the reality doesn’t allow it. Persecution arose from overlapping spheres:

- Geopolitical factors: being a small population amidst powerful empires.

- Religious hostility: especially from Christian doctrine steeped in theological mistrust.

- Economic roles: often limited yet visible, breeding envy and resentment.

- Cultural distinctiveness: language, customs, dress that made integration difficult.

- Minority status: vulnerable to scapegoating in times of crisis.

- Myths and conspiracy theories: irrational fears fueled by misinformation.

Each factor alone may not have resulted in such pervasive persecution, but combined, they created a combustible environment. And when harder times hit—plagues, wars, economic troubles—Jews were convenient targets.

What Can We Learn?

Understanding this layered history helps us grasp how fear of the “other,” religious narratives, economic dynamics, and social exclusion can fuse to devastating effect. Recognizing the self-fulfilling nature of persecution warns us against stereotyping or isolating minorities today.

Could societies benefit by fostering true inclusion and combatting myths rather than relying on age-old scapegoats? Absolutely. The survival and cultural richness of Jewish communities despite centuries of adversity offer a powerful lesson in resilience and the human spirit.

In Closing: Rethinking the Past to Shape the Future

The question “Why have Jews been persecuted so fervently and frequently?” is answered best not by placing blame on victims but by dissecting the historically rooted, multifaceted currents that swirled against them. From geopolitical location to economic niches, to religious doctrine and social dynamics—these currents intertwined, often tragically.

Recognizing this complexity can help us challenge antisemitism, and prejudice in general. It encourages a future in which no group’s difference becomes a license for persecution.

So, rather than asking “What’s wrong with THIS group?” we might ask: How can we build societies where differences enrich rather than endanger?

“In understanding history, we find the tools to reshape the future.”

Why were Jews frequently blamed for economic issues in medieval Europe?

Jews often worked as moneylenders because Christians were forbidden to charge interest. This led to resentment as Jews became wealthy in visible roles. Restrictions kept them in finance, fueling envy and myths about their economic power.

How did religious texts influence Jewish persecution in Christian Europe?

Passages in the Gospel of John portrayed Jews as hostile to Jesus, justifying centuries of suspicion. Christian doctrine often labeled Jews as ‘Christ-killers,’ a belief upheld until the 20th century and used to justify discrimination.

Why did having a distinct culture make Jews targets in many societies?

Jews preserved unique languages, customs, and religious practices, making them stand out. Their visible differences caused fear and suspicion, especially in mono-ethnic states, leading to social exclusion and scapegoating.

What role did political turmoil play in the persecution of Jews?

During times of crisis, like wars or plagues, Jews became scapegoats. Rulers and populations blamed them for misfortunes, such as disease outbreaks or military defeats, increasing violence like pogroms and expulsions.

How did Jews’ minority status contribute to recurring persecution?

Being a small minority confined Jews to certain roles and places. Their cohesion and visibility made them easy targets. Restrictions and forced isolation both protected and exposed them to repeated hostility.

Why have Jews faced persecution from so many different groups throughout history?

Jews lived near powerful empires, maintained distinct identities, and often held economic roles that fueled envy. Religious biases, scapegoating in crises, and societal fears combined to create persistent persecution across eras and regions.