The profound animosity between Sunnis and Shiites originates primarily from a dispute over who should lead the Muslim community after the death of the Prophet Muhammad. This disagreement evolved into a complex, long-lasting sectarian divide fueled by theological, ethnic, political, and social factors.

When Muhammad died in 632 CE, the question of succession sparked intense debate. Sunnis believe that the leader, or caliph, should be chosen through a consensus process among the community. They supported Abu Bakr, Muhammad’s father-in-law, as the first caliph. In contrast, Shiites maintain that leadership must remain within the Prophet’s family, specifically appointing Ali, Muhammad’s cousin and son-in-law, as the rightful first caliph. Ali was initially passed over and only became the fourth caliph. Shiites reject the legitimacy of the first three caliphs—Abu Bakr, Umar, and Uthman—and view Ali as Islam’s first true leader.

This fundamental disagreement led to early conflicts. After Ali’s assassination, Muawiyah, a rival leader, established a dynastic caliphate by passing leadership to his son, which Shiites opposed vehemently. Muhammad’s grandson Hussein led a revolt against this, ending tragically in his death and becoming a defining moment in Shiite identity and rituals of mourning.

The split deepened as Sunnis emphasized a legalistic approach to Islam, focusing on community consensus and jurisprudence. Shiites, however, highlighted a more experiential and mystical relationship with faith, focusing on the lineage of the Prophet and personal spiritual experiences. Ethnically, the largest Shiite population resides in Persia (modern-day Iran), distinct from the Arab origins of many Sunni groups, adding another layer to the division.

| Aspect | Sunni Perspective | Shiite Perspective |

|---|---|---|

| Leadership | Caliph chosen by community consensus | Leadership by Prophet’s bloodline, starting with Ali |

| Theological Approach | Legalistic, focusing on strict interpretation of Muslim law | Experiential, incorporating mystical elements and spiritual leadership |

| Historical View | Respect for first three caliphs | Reject the first three, consider Ali and descendants legitimate |

Early Muslim civil wars cemented the conflict. After the assassination of Uthman, the third caliph, Muslims split into factions supporting or condemning the killing. Ali’s cautious governance and eventual assassination led to further wars. These battles, known as the first fitna, mark the origins of the Sunni-Shia divide in violence and political rivalry.

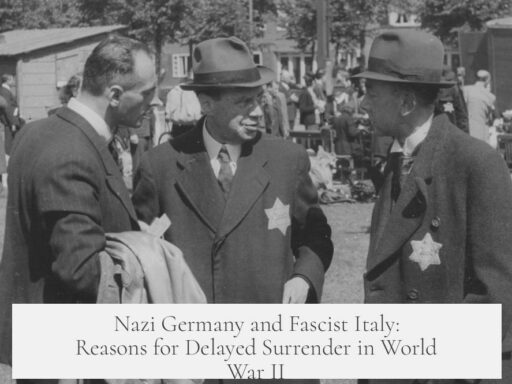

Modern factors amplify these historic tensions. In the 20th century, authoritarian regimes like the Ba’ath Party in Iraq and Syria aggravated Sunni-Shia rifts by promoting Sunni minority rule over large Shiite populations. British imperialism also played a key role after World War I, using divide-and-conquer tactics by elevating minority groups strategically to control the region. Such manipulation embedded mistrust on sectarian lines.

Proxy conflicts further worsen relations. Iran, a predominantly Shiite nation, supports groups like Hezbollah, advancing Shiite interests. Sunni regions often receive backing from Saudi Arabia, which funds Sunni groups with varying agendas. International players sometimes exploit Sunni-Shia rivalry to maintain regional influence. This “positive polarization” benefits political elites who profit from sectarian strife and instability.

In sum, the hatred between Sunnis and Shiites is not rooted solely in early leadership disputes. It spans centuries of religious interpretation, ethnic distinctions, violent conflict, political power struggles, and foreign interference. Over time, the sectarian split has become less about theology alone and more about geopolitics, social identity, and historical grievances, much like the Catholic-Protestant divide in Europe.

- The Sunni-Shia split began with disagreement over Muhammad’s rightful successor, focusing on community choice versus hereditary leadership.

- Early Muslim civil wars entrenched animosities and established sectarian identities.

- Theological and ethnic differences contributed to ongoing divisions beyond political leadership.

- 20th-century authoritarian regimes, colonial strategies, and modern proxy wars have intensified hostility.

- Current conflicts stem from a mix of religious, political, ethnic, and international influences rather than purely theological origins.