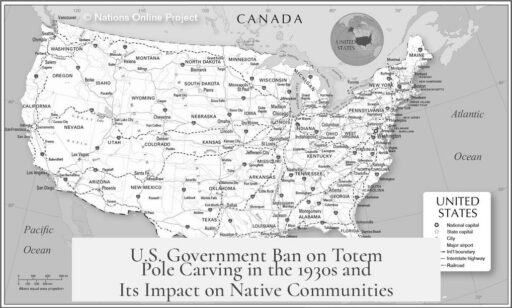

The U.S. government did not explicitly ban totem pole carving in the 1930s. Instead, totem carving faced effective suppression through a combination of legal, cultural, and social pressures rooted in earlier policies like the Code of Indian Offenses (1884), missionary-driven assimilation, and natural factors that diminished the presence and practice of carving among Native communities.

The Code of Indian Offenses, established in 1884 by the Office of Indian Affairs, served as a critical legal tool. Though totem pole carving itself was never directly prohibited, the Code empowered officials to ban Native ceremonies, disrupt religious and cultural practices, and confiscate or destroy sacred objects. This broad authority indirectly suppressed totem carving by targeting the cultural and spiritual contexts that supported it. Totem poles, often imbued with spiritual significance and linked to ceremony, fell under this suppression.

In Alaska, where many totem poles originate, federal government presence remained minimal until the 1940s. The limited enforcement of the Code meant that, legally, totem carving could have continued largely unaffected by the law alone during the 1930s. However, other factors played a decisive role in the decline of totem carving during this period.

Missionaries, alongside some Native community members who favored assimilation, exerted strong pressure against traditional practices. Assimilationist ideology held that integration into Western ways was essential for survival in a changing world. This belief led to discouragement and even abandonment of customs such as totem pole carving. The missionaries’ efforts included discouraging native languages, ceremonies, and arts, which disrupted the transmission of cultural knowledge to younger generations.

The consequences of these pressures became evident by the 1930s. A ‘lost generation’ of carvers emerged because fewer young Native individuals learned or chose to continue the art. This break in cultural transmission coincided with environmental factors: the Pacific Northwest’s coastal climate causes wooden totem poles to decay within about 75 years. Many poles erected in the 19th century naturally deteriorated or disappeared, with little replacement during the early 20th century.

For comparative context, Canada took a more direct legislative approach to suppress related cultural practices. The Canadian Indian Act of 1884 explicitly banned potlatching, a key ceremonial event tied to totem pole raising and cultural identity. This law had a clear and immediate impact on totem pole traditions in Canadian Indigenous communities. In contrast, the United States relied more on indirect suppression through legal frameworks like the Code of Indian Offenses and social assimilation policies.

Summarizing the situation in the United States during the 1930s:

- The U.S. government never explicitly banned totem pole carving.

- The Code of Indian Offenses allowed suppression of ceremonies and sacred objects, indirectly affecting totem carving.

- Assimilation pressures, driven by missionaries and some Native people, discouraged traditional carving practices.

- Environmental decay and a generation gap in carvers led to a decline in totem poles.

- Limited federal enforcement in Alaska meant no strong legal crackdown occurred during the 1930s.

- Canada, by contrast, banned potlatching ceremonies, resulting in a more overt cultural crackdown.

This combination of indirect legal authority, cultural assimilation, and natural loss of totem poles explains why totem carving declined during the 1930s in the U.S. Rather than a straightforward ban, the decline resulted from layered pressures undermining cultural continuity and practice.

Key Takeaways:

- The U.S. never issued a direct ban on totem pole carving.

- The Code of Indian Offenses indirectly stifled cultural practices tied to totem carving.

- Assimilationist efforts by missionaries and some Native allies reduced interest in carving.

- Environmental decay and a ‘lost generation’ of carvers led to fewer totem poles.

- Limited federal presence in Alaska delayed enforcement impacts.

- Canada took a harder stance by banning potlatching, closely linked to totem carving traditions.

Why Did the U.S. Government Ban Totem Pole Carving in the 1930s?

Let’s get straight to it: the U.S. government never actually banned totem pole carving outright in the 1930s. Instead, a complex mix of laws, cultural pressure, and environmental factors indirectly suppressed this vibrant Native tradition. It wasn’t a blunt “No to carving!” decree. It was more like a slow fade-out, played by government policies and social forces. Intrigued? Let’s unravel this compelling story.

First off, the key legal backdrop is the Code of Indian Offenses from 1884. Now, you might expect a ban to be loud and clear—“No more carving!” Yet, that’s not exactly how it worked. The Code didn’t explicitly say “totem poles are forbidden.” Instead, it granted officials the chilling power to ban Native ceremonies, disrupt religious practices, and even confiscate sacred objects. This blanket power could—and did—impact totem pole carving deeply because many poles serve sacred and ceremonial roles within tribes.

This law was aimed primarily at tribes in the Lower 48 states but extended to Alaska. So, while no direct ban existed, that legal framework created an atmosphere where carving, especially if tied to spiritual ceremonies, was risky. Officials could simply step in and declare these cultural acts illegal or immoral, allowing suppression without mentioning poles specifically.

But here’s a plot twist: the federal government barely had a footprint in Alaska until the 1940s. If the Code had been the only factor, totalling banning totem poles probably wouldn’t have happened. The government wasn’t constantly monitoring the coastlines and forests where totem poles stood proud. Instead, indirect forces played a bigger role.

Enter the missionaries and the complex web of assimilationist pressures. Many missionaries believed Native practices like totem carving hindered progress and “civilization.” They pushed Native groups to abandon their traditions, threatening cultural identity in many subtle ways. What’s more, some Native individuals accepted assimilation as the best survival tactic in a changing world. They discouraged traditional arts including totem pole carving, fearing these customs would alienate them from mainstream society.

Imagine being a young Native in the early 20th century, caught between preserving a rich heritage and surviving a rapidly shifting cultural landscape. The result? Fewer apprentices picked up chisels and axes. The “lost generation” of carvers emerged, and old poles, susceptible to weather and rot, began to vanish without replacement.

To put it succinctly, cultural erosion played a decisive role alongside any legal suppression. Totem poles, carved from cedar, usually survive about 75 years in the Pacific Northwest climate. By the 1930s many 19th-century poles were food for moss, rain, and time. With fewer new carvers motivated or trained, the craft dwindled.

A quick geographical neighbor comparison reveals a sharper restriction. Canada’s 1884 Indian Act explicitly banned the potlatch ceremony, a vital festival linked closely with totem pole raisings and overall tribal governance, identity, and wealth distribution. Without potlatching, the cultural ecosystem supporting totem carving collapsed rapidly in Canada. The U.S., by contrast, didn’t explicitly outlaw potlatches or carving but suffocated these through indirect assaults on Native spirituality and cultural expression.

What does this mean today? Despite federal silence on carving bans, the cumulative effect of policies, social pressures, and natural decay created a near-ban environment. Totem poles—silent storytellers of heritage—were endangered without a clear legal ban. The carvings almost disappeared by the 1930s because of a scattering of indirect but powerful forces pulling at cultural threads.

A Closer Look: How Did This Affect Native Communities?

- With federal presence light, communities relied on their own resilience to keep traditions alive.

- Assimilation led many to hide or stop ceremonies, including carving, out of fear or social shame.

- The “lost generation” means skill transmission broke, causing a cultural rupture that’s still felt now.

Oddly, the absence of a direct ban sometimes made advocacy and revitalization trickier. There was no single legal rule to challenge or overturn. Instead, Native communities and allies worked over decades to rebuild interest in carving, teaching younger generations, and reclaiming the significance of totem poles.

Here’s a takeaway: cultural survival often battles not only overt laws but invisible currents like social pressure, economic hardship, and environmental challenges.

So, What Can We Learn from This?

We know that tradition doesn’t vanish just because a law says so. It crumbles under the weight of neglect, fear, and forced change. The story of totem pole carving reminds us that safeguarding culture requires protecting the conditions around it—the people, the ceremonies, and the environment.

If you visit the Pacific Northwest today, you’ll see a revival of totem carving—a testament to resilience. But next time, think about the invisible fences that once hemmed in this craft. How can we better support cultural practices that face indirect threats? What hidden rules shape what traditions survive? These questions are as relevant now as they were in the 1930s.

In short, the U.S. government’s ban on totem pole carving in the 1930s was less a direct edict and more an echo of a broader, quieter suppression through the Code of Indian Offenses, assimilation pressures, and cultural fracture. That nuanced history deepens our understanding of how policy and culture intertwine—and sometimes strangle.

Ready to explore more Native American cultural resilience stories? Stay curious, and keep digging beneath the surface.

Why did the U.S. Government never explicitly ban totem pole carving in the 1930s?

The government used the Code of Indian Offenses from 1884 to indirectly suppress Native practices. This law allowed officials to ban Native ceremonies and destroy sacred objects, affecting totem carving without naming it specifically.

How did assimilation pressures contribute to the decline of totem pole carving?

Missionaries and some Native people supported assimilation, discouraging traditional cultural practices. This led to fewer young carvers learning the craft, causing a decline in totem pole creation by the 1930s.

Did the U.S. Government enforce the ban on totem pole carving strictly in Alaska?

Federal presence in Alaska was limited before the 1940s. Without strong enforcement, legal restrictions had less direct impact. Social and cultural pressures played a bigger role in reducing totem carving.

How did the Canadian approach to totem pole culture differ from the U.S. in the 1930s?

Canada passed the Indian Act in 1884, banning potlatching, a key ceremony linked to totem raising. The U.S. did not impose such explicit bans, though it used indirect legal and social controls.

What role did environmental factors play in the decline of totem poles in the 1930s?

Totem poles naturally decay within about 75 years in the Pacific coast climate. Combined with fewer new carvers due to cultural suppression, this led to many poles disappearing by the 1930s.