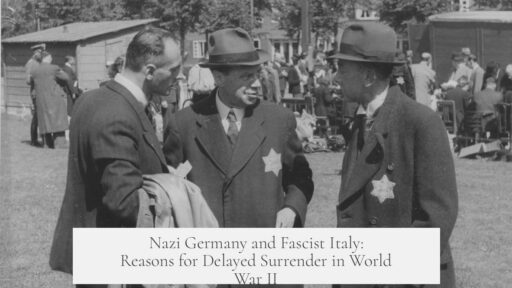

Nazi Germany and Fascist Italy only surrendered after losing World War II for several years due to a complex mix of ideological commitments, strategic miscalculations, fear of Allied policies, and psychological factors within their leadership. Both regimes maintained resistance even as defeat became inevitable. They delayed surrender because unconditional surrender terms were harsh, and their war aims were deeply ideological, tied to notions of racial supremacy and total victory.

Italy formally surrendered in September 1943, shortly after the Allied invasion of Sicily. However, Germany quickly reacted by occupying northern and central Italy, installing Mussolini as the head of a puppet regime called the Italian Social Republic. German forces occupying Italy continued fighting fiercely until the final weeks of the war. This demonstrates that Italian surrender did not immediately end Axis resistance in that region.

The delayed surrender of Nazi Germany is more complicated. Nazi war goals were not limited to territorial control. They focused on establishing German dominance over Europe, carrying out ethnic cleansing, and defeating Bolshevism. These goals dictated a total war strategy in which destruction was a tool, not a side effect. This ideological fanaticism made it difficult for Nazi leadership to consider surrender as a viable option.

Misbeliefs and overestimations shaped German strategic decisions for years after the war turned against them. The Nazi leadership hoped to negotiate peace with Western Allies, creating a united front against the Soviet Union. Hitler remained overly confident in the Wehrmacht’s abilities, demanding last stands in so-called “fortress cities” and ordering futile counterattacks despite clear shortages in manpower and resources.

Hitler’s ideological stance profoundly influenced his refusal to surrender. He saw surrender as a personal betrayal of the German master race’s destiny to conquer Europe. With defeat imminent, surrender was equated to national disgrace and the end of Germany as a concept. He maintained a “victory or death” mentality, rejecting any peace that did not secure Nazi aims.

Allied policies further discouraged surrender. The Allies had committed themselves to accepting only unconditional surrender, a stance agreed upon at Tehran and reiterated at Yalta. For Germany, unconditional surrender meant losing sovereignty and facing occupation or division. Plans like the Morgenthau Plan, which aimed to deindustrialize and turn Germany into a farming nation, were well-known, deterring surrender.

The prospect of war crimes trials also caused hesitation. The Allies agreed in 1943 to prosecute Axis leaders for their crimes, raising fears among Nazi officials of prosecution and execution. This fear contributed to their willingness to fight to the very end rather than surrender.

The Soviets’ rapid advance and the reported brutality of their troops strengthened the Nazis’ resolve to continue fighting. Tales from retreating soldiers about harsh Soviet reprisals made German troops and civilians eager to resist, fearing retribution worse than continued war.

In early 1945, German leaders attempted to negotiate an armistice that might divide the Western Allies and the Soviets, hoping to secure better terms. The “Bern Incident,” led by Karl Wolf, was an effort to open talks but was never intended as a full surrender. This strategy failed and reflected their hope to improve conditions rather than concede defeat.

Psychological factors also played a key role. Hitler and many Nazis viewed surrender as shameful and inconsistent with their propaganda. For them, dying or committing suicide appeared more honorable than capitulation. Hitler’s suicide in April 1945 marked the end of the leadership’s ideological resistance, though some German forces still fought briefly afterward.

| Factors | Impact |

|---|---|

| Ideological War Aims | Refusal to surrender to preserve Nazi racial and political goals. |

| Strategic Miscalculations | Overestimation of military capabilities and hope for peace with Western Allies. |

| Unconditional Surrender Policy | Hardened Nazi stance against surrender to avoid loss of sovereignty and trials. |

| Red Army’s Advance | Reports of brutality motivated continued German resistance. |

| Psychological Factors | Aversion to surrender; preference for death or suicide among Nazi leaders. |

These combined reasons explain why Nazi Germany and Fascist Italy only surrendered after extended fighting despite the Allies’ clear ascendancy. Their surrender was not a mere military decision but tied to ideological resolve, fear of consequences, and hope, however unrealistic, for improved conditions or victory.

- Italy surrendered in 1943 but German forces continued fighting in occupied zones.

- German surrender delayed by ideological war aims focused on racial conquest and destruction.

- Nazi leadership overestimated strength and hoped for peace with Western Allies.

- Allied insistence on unconditional surrender discouraged Nazi capitulation.

- Fear of war crimes trials and Soviet brutality motivated continued resistance.

- Hitler’s ideological stance and psychological factors made surrender unacceptable.

- Attempts to negotiate separate peace failed, prolonging the conflict.

Why Did Nazi Germany and Fascist Italy Only Surrender After They Had Been Losing the Second World War for a Couple Years?

The short answer is this: Nazi Germany and Fascist Italy clung to power despite sinking for years because of deep ideological commitment, strategic illusions, fear of disgrace, and rigid Allied surrender demands. Their delayed surrender wasn’t just stubbornness; it was a complex dance of ideology, hope, and sheer terror of what total defeat meant.

Let’s unpack this complex historical puzzle. Why hang on when defeat is so obvious? The story is layered with ideology, psychological blocks, military miscalculations, and Allied policies that shaped the endgame.

Italy’s Early Surrender and Germany’s Grip

Italy was the first Axis power to fold its cards. In September 1943, a couple of months after the Allies stormed Sicily, Italy formally surrendered. But wait, the plot thickens. Rather than a clean exit for the Axis, Germany quickly swooped in.

German troops took control of much of Italy, installing a puppet government with a rescued Mussolini as the head. These German forces in Italy held on stubbornly and didn’t surrender until the war’s final weeks. So, Italy’s surrender didn’t mean the war in Italy was over immediately; it just took on a new face.

Why Did Nazi Germany Hold Out So Long?

The heart of the delay lies in the Nazi worldview. This wasn’t a conventional war over land or resources. The Nazis fought for a brutal ideology centered on conquering Europe, cleansing its peoples, defeating Bolshevism, and solving the “Jewish Question” with horrific means. Death and destruction weren’t collateral damage—they were part of the goal.

Given this mindset, surrender wasn’t just a military decision; it was existential. Hitler and many top Nazis refused to accept defeat because their vision was fundamental to their identity. Surrender meant abandoning the dream of a racially “pure” empire and admitting personal failure—a bitter pill to swallow.

To make matters worse, Nazi leaders held onto numerous misbeliefs. Some imagined they could split the Allies and find a deal with the Western powers, uniting against the USSR. Others, including Hitler, grossly overestimated the army’s ability to fight on. They ordered doomed last stands in fortress cities and pointless counterattacks, ignoring the realities on the ground.

The Unyielding Enemy: Allies’ Demand for Unconditional Surrender

Now, picture the other side. The Allies agreed — first at Tehran, then Yalta — that they would only accept unconditional surrender. This meant total defeat. For Germany, unconditional surrender was a nightmare. It implied occupation, loss of sovereignty, and the end of the Nazi state as they knew it.

The notorious Morgenthau Plan, which proposed turning Germany into a rural wasteland, was widely known and terrifying. Combine that with the knowledge that top Nazis would face war crimes trials (decided in Moscow in 1943), and surrender looked awful.

Adding to the dread were stories from the front. The Red Army’s rapid advance was brutal. Retreating German soldiers shared tales of atrocities, making many fear what would befall their families and homeland if they gave in. This increased the urgency to hold on, pointless as it seemed.

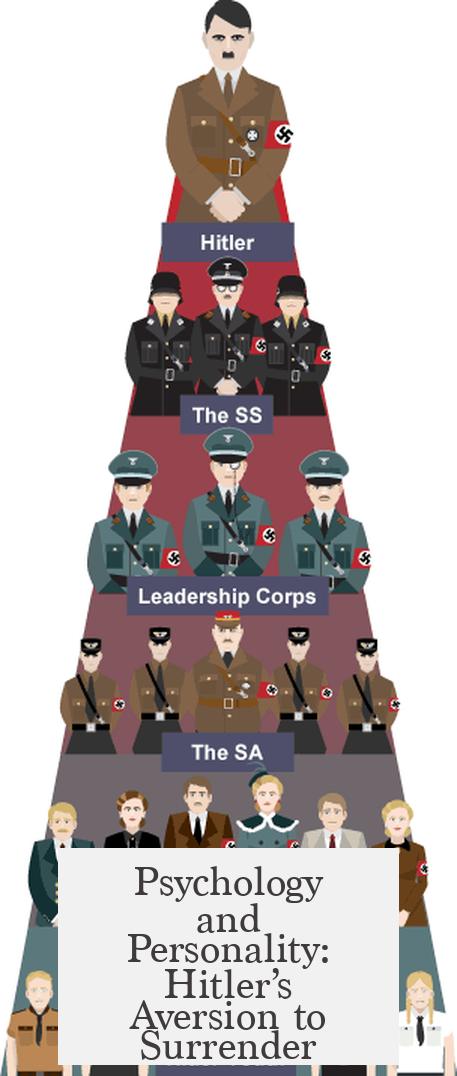

Psychology and Personality: Hitler’s Aversion to Surrender

Hitler’s mindset was a fortress of denial. Even when he knew the war was lost in the final weeks, surrender was never on the table. For him, defeat meant not peace but annihilation. The notion that Germany, the so-called master race, could fail was unthinkable and a personal betrayal.

Many Nazis preferred death over surrender. Cyanide pills were more popular than negotiating peace because surrender contradicted everything they had preached and fought for.

Last-Ditch Efforts to Divide the Allies

Even in the desperate final months, Germany tried to manipulate the situation. In 1945, shortly after Yalta, the Nazis attempted a secret armistice offer through Karl Wolf, an SS commander in Northern Italy.

This move — known as the Bern Incident — aimed not to surrender but to create cracks between the Allies. They knew Stalin feared a separate peace between Germany and the West and attempted to exploit that. However, the plan failed, and the Allies remained united in demanding unconditional surrender.

What About Italy’s Puppet Regime? Did It Change Anything?

When Germany crushed Italy’s initial surrender, installing Mussolini as a figurehead, it bought them extra time. The German forces remained engaged and resistant well into 1945. This extended the war in Italy and dragged down Allied efforts.

The puppet state was a strategic lifeline for Germany in a country they had once called an ally but now saw as a traitor state.

Summary: A Mix of Fear, Ideology, and Strategy

The delayed surrender of Nazi Germany and Fascist Italy wasn’t due to simple stubbornness or bad luck. It was a knot of ideological fanaticism, flawed leadership judgments, harsh Allied terms, and fear of total destruction.

Unconditional surrender was a bitter prospect. It meant occupation, loss of sovereignty, prosecution as war criminals, and harsh treatment. Germany’s leadership wanted to avoid this at all costs. Even after Hitler’s suicide, they tried to negotiate surrender terms in hopes of better conditions, but the Allies rejected any compromises.

In the end, the Axis’s refusal to surrender early cost millions of lives and prolonged Europe’s suffering. Their story is a grim lesson on how ideology and pride can blind leaders to reality, even when the writing’s clearly on the wall.

So, What Can This Teach Us Today?

History tells us surrender isn’t always about weakness — sometimes it’s about survival, stubbornness, fear, or misguided hope. Understanding the Axis leaders’ mindset reveals how dangerous ideological fanaticism can be, especially when combined with harsh demands from the other side.

Next time you hear someone wonder why dictators won’t just quit when losing, remember Nazi Germany and Fascist Italy. Surrender isn’t always simple. Sometimes, it’s the hardest choice of all.