The Nazis burned books that challenged their ideology, targeted ethnic and political groups they opposed, and represented ideas they deemed harmful to their regime. These book burnings occurred mainly in 1933 and featured works from Jewish authors, leftists, pacifists, and critics of Nazism. Notable authors included Bertholt Brecht, Erich Maria Remarque, Stefan Zweig, and foreign writers such as Ernest Hemingway.

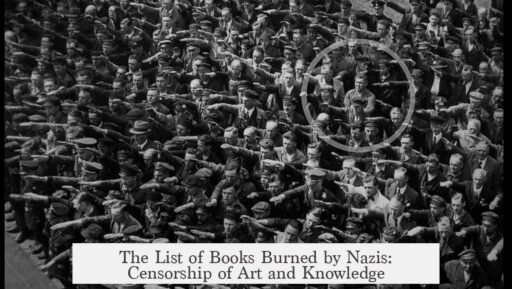

The Nazi book burnings began shortly after Hitler rose to power. In April 1933, the German Student Union (Deutsche Studentenschaft, or DSt), under local Nazi influence, initiated plans to destroy anti-Nazi literature. They aimed to publicly display their dominance through rallies and symbolic destruction of the books. This plan grew quickly, culminating in coordinated events by mid-May. On May 10, 1933, rallies occurred throughout Germany where students gathered targeted books and set them ablaze.

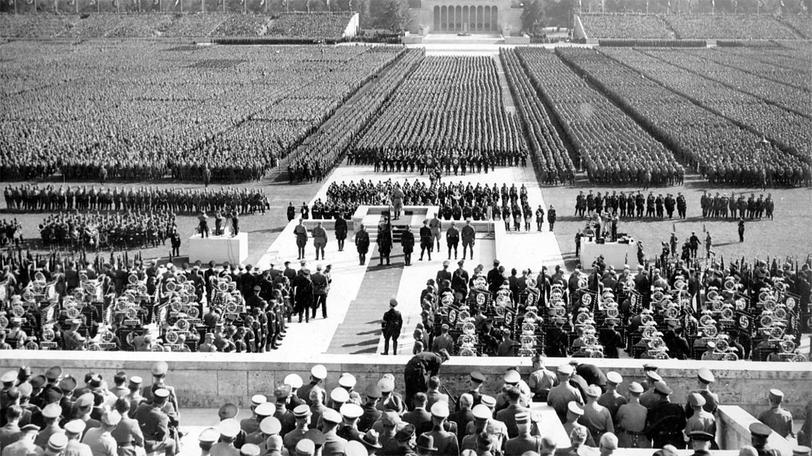

The largest and most famous burning took place in Berlin with around 40,000 spectators. Nazi propaganda minister Joseph Goebbels spoke at this event, praising the students for purging the “Jewish intellectual scourge.” This book burning served both as propaganda and a cultural purge. The Nazis sought to eliminate materials that threatened their worldview or revealed uncomfortable truths about war, peace, or race.

There was no single Nazi office that officially dictated what books to burn early on. Instead, regional party officials and ideologues made decisions. Dr. Wolfgang Herrmann, a Berlin library administrator allied with the Nazis, compiled a list of 134 authors and works that locals then distributed widely. Although Herrmann’s list gained prominence, it never received formal endorsement from Goebbels or the top Nazi leadership.

The books chosen included works by authors identified as Jewish, left-wing, pacifist, or simply critical of Nazi policy. Some examples of banned German-language authors include:

- Bertholt Brecht

- Max Brod

- Erich Maria Remarque (famous for All Quiet on the Western Front)

- Stefan Zweig

Foreign authors such as Ernest Hemingway, Jack London, and Upton Sinclair also appeared on the lists. These writers were viewed as subversive or anti-German because their works criticized nationalism, fascism, or imperialism.

As the Nazi apparatus grew, other groups expanded upon Herrmann’s initial list. For instance, the State of Prussia published a broader banned-books list in the Börsenblatt für den Deutschen Buchhandel (Trade Magazine for German Booksellers). This expanded list included Thomas Mann, winner of the 1929 Nobel Prize in Literature, whose vocal criticism of Nazism made him a target. His brother Heinrich Mann was already on the earlier lists.

Besides political and racial targets, the Nazis also went after specialized scientific and cultural materials. For example, on May 10, 1933, the Nazis seized and burned the collection of Dr. Magnus Hirschfeld’s Institute for Sexual Research in Berlin. Hirschfeld, a Jewish and openly gay physician, had created one of the first modern sexology centers. His institute contained pioneering LGBT research and materials promoting sexual minorities. These were destroyed as part of a broader cultural cleansing. Hirschfeld and many of his colleagues had fled Germany by then, so the Nazis met no resistance.

In summary, Nazi book burnings targeted:

- Works by Jewish authors and intellectuals

- Books by leftists, socialists, communist sympathizers

- Pacifist and anti-war literature

- Foreign authors critical of fascism and nationalism

- LGBT research and related scientific work

- Any materials deemed “anti-German” or subversive to Nazi ideology

The Nazi book burnings stand as a chilling example of cultural repression used to consolidate power. They terrorized intellectuals, censored free thought, and symbolized the regime’s drive to reshape society along totalitarian lines.

| Category | Examples | Reason for Ban |

|---|---|---|

| Jewish Authors | Max Brod, Stefan Zweig | Ethnic persecution |

| Leftists & Critics | Bertholt Brecht, Heinrich Mann | Political opposition |

| Anti-War Literature | Erich Maria Remarque | Pacifism seen as weak or subversive |

| Foreign Authors | Ernest Hemingway, Jack London | Opposition to nationalism/fascism |

| LGBT Research | Magnus Hirschfeld’s Institute works | Suppression of sexual minorities |

- The Nazi book burnings began in April 1933 shortly after Hitler became chancellor.

- The German Student Union organized rallies to burn banned books, with the largest event in Berlin attended by 40,000 people.

- Dr. Wolfgang Herrmann compiled a key list of authors and works considered undesirable, though there was no single, official list.

- Books by Jewish, leftist, foreign, and pacifist authors were targeted.

- LGBT research materials, especially from Magnus Hirschfeld’s Institute, were also destroyed.

What Books Did the Nazis Burn? Unraveling the Flames of Censorship

So, what books did the Nazis burn? Right after Hitler became chancellor in early 1933, the Nazi regime wasted no time targeting literature that clashed with their dark agenda. This wasn’t just random arson; it was a well-orchestrated campaign against ideas and authors who opposed or didn’t fit the Nazi worldview, literally tossing their books into massive bonfires to erase dissent.

By May 1933, the German Student Union (Deutsche Studentenschaft, or DSt), a key Nazi-affiliated group, was at the forefront of these fiery spectacles. Imagine crowds gathering in dozens of German cities, with bonfires blazing and speeches roaring. The largest event, held in Berlin, drew a staggering 40,000 people. Joseph Goebbels, Nazi propaganda master, even praised these rallies as a battle against the “Jewish intellectual menace.” No, this wasn’t just a book burning; it was a symbolic scorning of free thought.

But which books and authors exactly did this campaign target?

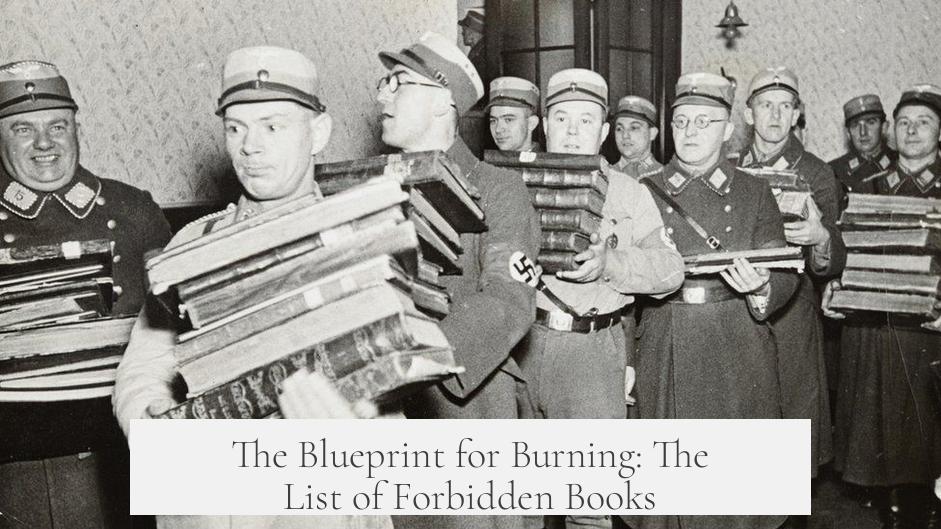

The Blueprint for Burning: The List of Forbidden Books

Before Goebbels fully centralized cultural control through his Ministry of Propaganda, local Nazis and student groups had a lot of freedom in deciding what to burn. One Berlin library administrator and Nazi functionary, Dr. Wolfgang Herrmann, played a pivotal role. He compiled a list of 134 authors and works that clashed with Nazi ideology. This list didn’t have official Nazi ministry approval but quickly spread among student groups and local leaders nationwide.

The selections were no accident. The Nazis singled out ethnic minorities, leftists, critics of Nazism, and pacifists. The goal was clear: obliterate voices that challenged their doctrine or highlighted uncomfortable truths.

Familiar Names in Flames

This infamous list featured some heavy hitters of literature, many of whom you might recognize today:

- Bertholt Brecht: A sharp critic of fascism, whose plays highlighted social injustice.

- Max Brod: Franz Kafka’s friend and literary executor, whose works were considered tainted for Jewish heritage.

- Erich Maria Remarque: Author of All Quiet on the Western Front, a chilling anti-war novel exposing World War I horrors.

- Stefan Zweig: Celebrated Austrian-Jewish writer, known for his humanistic approach.

Even non-German writers weren’t safe. The Nazis included foreign authors like Ernest Hemingway, Jack London, and Upton Sinclair—writers known for their critiques of capitalism, war, and social injustice.

Expanding the List: Thomas Mann and Beyond

Later, these bans got more stringent and expansive. Other Nazi factions borrowed heavily from Herrmann’s initial list but added more names. For example, Nobel laureate Thomas Mann, who openly criticized the Nazis, didn’t escape the flames. His brother, Heinrich Mann, was already on the original list. The inclusion of their works was a loud message: no intellectual or dissident voice would be tolerated.

Burning Books and Burning Knowledge: The Case of LGBT Research

Here’s a particularly grim chapter: on May 10, 1933, during the massive DSt Berlin rally, the Nazis didn’t just target novels and essays. They destroyed the entire library of Dr. Magnus Hirschfeld’s Institute for Sexual Research. This institute pioneered the scientific study of sex, gender, and homosexuality—it was the world’s first pro-LGBT research center. Hirschfeld himself was both Jewish and gay, making him a prime target. His institute’s collection of pioneering works was seized and incinerated with zero resistance since Hirschfeld and his colleagues had fled. This act wasn’t just censorship—it was an attempt to erase an entire field of knowledge and identity.

Why Did the Nazis Burn These Books?

The Nazi book burnings were much more than dramatic spectacles. They were a way to shape ideology and culture through fear and suppression. The regime aimed to wipe out what it called “un-German” ideas—whether political dissent, Jewish culture, pacifism, or anything promoting diversity in thought and identity.

Imagine schools, libraries, universities stripped of critical voices overnight. It’s horrifying but effective. By banning these books, the Nazis controlled what the public could read, think, and eventually believe.

Lessons From the Flames: Why Does This Matter Today?

Why dig into this depressing history? Because book burning is never just about books—it’s about control, censorship, and silencing. It’s a stark warning: when governments try to decide what is safe to read or think, freedom dies a little more each day.

Today, remembering what books the Nazis burned helps safeguard our right to read diverse voices, question authority, and celebrate free thought.

Next time you pick up a banned or controversial book, ask yourself: what ideas are we risking if these voices are silenced?

What types of books did the Nazis target for burning?

The Nazis targeted books by Jewish authors, leftists, and critics of Nazism. They also banned works seen as subversive, anti-war, or “anti-German.” Many prominent authors like Bertholt Brecht and Erich Maria Remarque were included.

Were the lists of banned books standardized by the Nazi leadership?

No. Early on, there was no single Nazi authority deciding the banned books. Local leaders and groups made their own lists. Herrmann’s list was widely used but never officially approved by top Nazi leaders like Goebbels.

Did the Nazis burn works from foreign authors as well?

Yes. Foreign writers such as Ernest Hemingway, Jack London, and Upton Sinclair were on the banned lists. Their works were considered harmful to Nazi ideology and were included in the burnings.

What was the significance of the May 10, 1933 book burning event?

This nationwide event organized by the German Student Union marked the start of mass burnings. It included tens of thousands of people, with a large gathering in Berlin where Joseph Goebbels spoke. Books from Hirschfeld’s LGBT research institute were also burned then.

Were any Nobel Prize-winning authors banned or burned by the Nazis?

Yes. Thomas Mann, a Nobel Prize winner, was an outspoken critic of Nazism. His works, along with those of his brother Heinrich Mann, were added to expanded banned books lists used in regions like Prussia.