Emperor Nero is often portrayed as a ruthless, immoral tyrant, but this image simplifies a complex historical reality. His reign started with promise and effective governance under strong advisors but deteriorated into cruelty and excess. While many charges against him hold merit, some negative portrayals are exaggerated or biased by class interests.

The main historical sources on Nero’s reign come from Tacitus, Suetonius, and Cassius Dio. Each wrote decades after Nero’s death, drawing from independent accounts. Interestingly, all three depict Nero’s rule in two phases: a stable, even positive first five years (54-59 CE), followed by a turbulent final nine years marked by tyranny and excess.

The initial period benefited from the guidance of Nero’s tutor Seneca and the praetorian prefect Burrus. During this phase, Nero showed promise as a ruler. But the turning point came in 59 CE when Nero ordered the murder of his mother, Agrippina. This act shocked Roman society and marked the beginning of his more infamous behaviors.

Several accusations define Nero’s legacy. He murdered family members, including his own mother and wife, confirming his ruthless streak. His personal life was marked by immorality and sexual licentiousness, which scandalized the Roman aristocracy. Nero also bankrupted the state through extravagant spending dedicated to his artistic and architectural ambitions.

Nero’s public performances in singing and dancing defied elite Roman norms and violated expected decorum. He is reported to have forced senators to attend or even participate in these shows, undermining their dignity and alienating the ruling class. This behavior contributed significantly to his poor reputation among the elites.

The Great Fire of Rome in 64 CE remains a contentious issue. Suetonius and Cassius Dio claim Nero started the fire to clear land for his grand palace, the Domus Aurea. However, Tacitus, known for his skepticism, suggests the fire was accidental, beginning far from Nero’s palace. The popular rumor that Nero “fiddled while Rome burned” likely emerged from these suspicions. Moreover, Nero blamed Christians, leading to brutal persecutions viewed as scapegoating.

Another significant charge is that Nero favored the Greek Eastern provinces over the rest of the empire. Historical records show he relieved territories like Achaea from taxation and even contemplated moving the imperial capital to Alexandria. This bias irritated Italian and Roman elites who felt neglected.

Nero’s harsh treatment of aristocratic critics deepened his troubles. He persecuted senators like Thrasea Paetus and even his mentor Seneca, reflecting his failure to build stable relationships with the ruling class. Since the emperor relied heavily on aristocrats to govern, Nero’s alienation of this group eroded his power base.

Despite these well-documented abuses, some charges against Nero appear exaggerated or influenced by bias. Accounts of his sexual depravity vary widely, hinting at sensationalism. The idea of Nero as an unrelenting villain fits conservative Roman aristocrats’ burlesque narratives. They often had personal and political motives to depict him negatively. Meanwhile, the Greek East remembered Nero more fondly, and his lingering popularity there led to several false claimants after his death.

Tacitus noted that Nero’s unpopularity mainly resided among the upper classes. The common people of Rome reportedly mourned him, indicating a divide in perception. Nero’s attention to public entertainment and relief for provincial areas earned him support beyond senatorial circles.

Ultimately, Nero’s greatest failure was his inability to maintain the delicate balance required of a Roman princeps. The emperor was “first among equals” and needed to cooperate with the Senate and aristocracy. His disrespect toward senators and summons to forced participation alienated this essential group. A vicious cycle formed: Nero’s behavior caused aristocratic resistance, leading to purges from his side, which then increased hostility.

The historical portrayal of Nero as solely evil lacks nuance. He committed brutal acts and exercised poor judgment. However, some negative depictions are magnified by class prejudice and posthumous rumors. His early reign held promise that slipped away as power corrupted him and strained relationships with elite Romans.

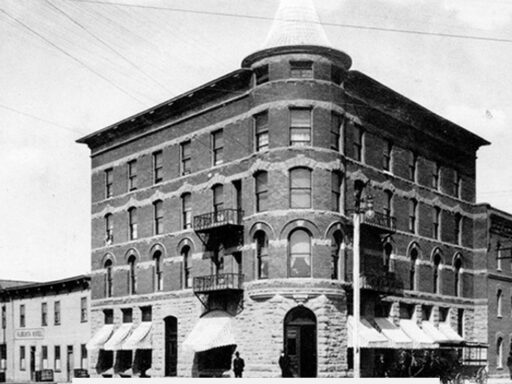

| Aspect | Evidence | Notes |

|---|---|---|

| Murder of Family | Multiple sources confirm | Highly likely true |

| Theatrical Performances | Many anecdotes and artifacts | Accurate but scandalized elite norms |

| Great Fire of Rome | Contradictory reports | Most historians doubt Nero caused it deliberately |

| Persecution of Christians | Multiple contemporary accounts | Probable scapegoating after fire |

| Favoring Greek East | Imperial edict freeing Achaea from taxes | Confirmed bias, may have political motives |

| Sexual Depravities | Inconsistent accounts | Possibly exaggerated |

- Nero’s early reign was competent under Seneca and Burrus’s guidance.

- He committed severe crimes, including family murders and political purges.

- Some charges, like sexual excesses, may be sensationalized.

- He upset aristocracy by forcing performances and treating senators disrespectfully.

- The Great Fire’s cause remains uncertain; Nero likely did not start it.

- Nero lost aristocratic support, a key to maintaining power in Rome.

- Lower classes and Eastern provinces maintained some loyalty toward Nero.

Was Emperor Nero Actually as Evil as He Is Often Portrayed?

Emperor Nero might be one of history’s most infamous figures, but was he really the monstrous villain that history paints him to be? The short answer is: not entirely. This post dives into the truth behind Nero’s notorious reputation, peeling back layers of biased ancient accounts and revealing a more complex man.

Let’s explore what the ancient sources say, the nature of the charges against him, and whether those claims hold up under scrutiny. Along the way, we’ll uncover how perspective shaped Nero’s legacy—sometimes unfairly.

The Ancient Historians: Our Main Sources

Our knowledge about Nero mainly comes from three Roman historians: Tacitus, Suetonius, and Cassius Dio. Each wrote decades, even centuries, after Nero’s death—Tacitus and Suetonius about 50 years later, and Cassius Dio some 150 years afterward. They mostly wrote independently, though sometimes they drew on common material.

Interestingly, none of these historians flat-out demonize Nero without nuance. They generally mark a clear division in his reign. The first five years (54-59 CE) are depicted as “good”—a time when Nero was under the influence of his tutor Seneca and military commander Burrus, who helped him steer the empire sensibly.

It’s only after 59 CE, when Nero killed his own mother Agrippina—the moment the narrative shifts dramatically, painting him as an increasingly tyrannical and debauched ruler.

The Charges Against Nero: What Did They Say?

- Murdering family members: Nero did kill his mother and later his wife. No controversy there—multiple sources confirm these acts.

- Immorality and licentiousness: Tales of his sexual escapades made the rounds, but historians caution these might be exaggerated.

- Financial recklessness: Nero spent lavishly, driving the state into debt, fueling rumors of bankruptcy due to his own indulgences.

- Theatrical antics: Far from the sober Roman ideal, Nero staged public performances—singing, dancing—and allegedly forced senators to attend or even take part.

- The Great Fire of Rome: Some accuse Nero of deliberately starting the fire to clear land for his grand palace, the Domus Aurea. Tacitus disagrees, believing the fire was accidental.

- Neglect of the empire: Nero favored the Greek Eastern provinces greatly and even considered moving the capital from Rome to Alexandria.

- Persecution of political enemies and Christians: He targeted aristocrats opposing him and brutally tortured Christians, blaming them for the fire.

Are These Charges True? Let’s Sift Fact from Fiction

Most accusations do hold weight—but with important nuances. The murders of key people like his mother and wife are well-documented. His conflict with senators such as Thrasea Paetus and repression of his former tutor Seneca also appear in multiple historical accounts. So these events are highly unlikely to be fabrications.

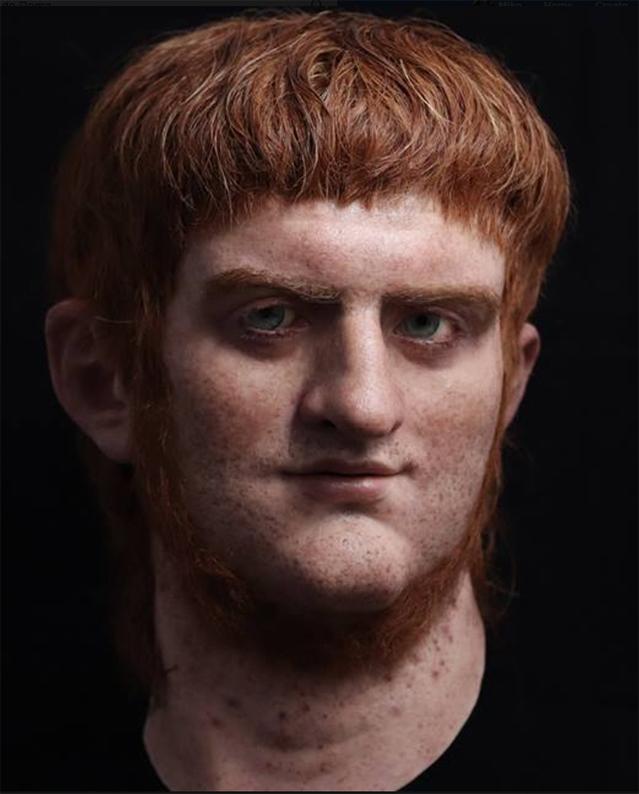

His passion for the arts and theatrical hobbies? Well, yes. He was quite fond of poetry, singing, and performing. We even have surviving fragments of his admittedly poor poetry. Plus, forcing senators to watch his acts was a breach of Roman social norms and ruffled many aristocratic feathers.

As for the Great Fire of Rome, the theory that Nero intentionally set it to build his golden palace is probably more legend than fact. Tacitus, the most reputable of his historians, thought the fire started accidentally—and nowhere near Nero’s new palace site, anyway. But thanks to Nero’s unpopular standing, rumors pinned the blame on him, igniting a wildfire of conspiracy theories.

The tales of his sexual excesses—well, they get wilder with every telling. Historians agree these stories were exaggerated or distorted over time, becoming part of his infamous mythos rather than cold facts.

The Role of Perspective: Who Are the Real Historians?

Here’s where things get interesting. Almost all the sources criticizing Nero come from the viewpoint of the Roman aristocracy—the very elite class Nero often clashed with. These historians wrote with conservative values, defending the senatorial order that Nero displeased. Naturally, they portrayed him as a tyrant and moral degenerate.

On the other hand, the Greek eastern provinces remembered Nero far more fondly. Signs of his popularity there endured through multiple “false Neros” who repeatedly claimed his identity after his death to rally support.

What’s more, Tacitus himself notes that the common Roman lower classes were actually upset by Nero’s death. The emperor’s unpopularity seems to have been mostly confined to the elite aristocracy.

The Emperor’s Big Mistake: Alienating the Aristocrats

Under Rome’s Principate system, emperors were supposed to work with the aristocracy. The emperor was princeps, “first among equals,” expected to show respect and collaboration with senators who ran much of the empire’s administration.

Nero struggled here. He didn’t treat senators as peers but rather as obstacles or rivals. His purges of opposition senators, including major figures like Thrasea Paetus, set off a vicious cycle of fear, plotting, and retribution.

This breakdown in relations with the elite hurt Nero’s ability to govern effectively and cemented his negative legacy in aristocratic writings.

So, Was Nero Really That Evil?

Nero certainly committed acts we’d judge harshly today: killing family, persecuting enemies, reckless spending, and probably poor leadership. Yet labeling him as pure “evil” oversimplifies a complicated legacy shaped by bias and political conflict.

He was a flawed ruler who made serious mistakes—especially in managing Rome’s powerful elite. His artistic hobbies and favoritism toward the Greek East marked him as unconventional, which irked conservatives.

But for all his faults, Nero wasn’t a one-dimensional monster. The positive early years of his rule, the lingering affection from the lower classes and Greek provinces, and the exaggerated rumors about his decadence paint a more nuanced portrait.

What Can We Learn From Nero’s Story?

Perhaps the biggest takeaway is how historical reputations form and what influences them. When powerful elites control the narrative, villains are often created to protect their interests.

Next time you hear stories about Nero fiddling while Rome burned (which is false—no fiddles in ancient Rome, and Tacitus says Nero wasn’t even in the city), pause and consider: Whose perspective is this? What agendas might they have had?

Bonus: Practical tips for spotting historical bias:

- Check the source: Is the historian close in time to the events? Do they have a known political agenda?

- Look for consistency: Are multiple independent sources agreeing, or just a single hostile account?

- Notice exaggerations: Sensational stories often signal embellishment or propaganda.

- Consider context: What social or political groups might have influenced the narrative?

In the end, Emperor Nero is a case study in how rulers get remembered—never fully good or fully evil, always shaped by the complex interplay of power, politics, and storytelling.

So the next time someone sums up Nero as history’s ultimate villain, feel free to respond with a wink: “Well, he sure was complicated.”

Was Nero truly responsible for the Great Fire of Rome?

Most historians think the fire was an accident. The claim Nero started it to build his palace comes mainly from Suetonius and Dio. Tacitus, a key source, doubts Nero’s involvement and shows the fire began away from Nero’s new palace.

How reliable are the ancient sources about Nero’s crimes?

Events like Nero killing his mother and wife are well-attested in multiple sources, so they are likely true. Tales about his sexual behavior are more varied and may be exaggerated over time.

Did Nero have any support during his reign?

Yes, the Greek eastern provinces liked Nero. Many false claimants appeared after his death trying to imitate him, suggesting lasting popularity. Also, lower classes in Rome were upset when he died, indicating some support.

Why did Nero have such bad relations with the Roman aristocracy?

Nero failed to respect and cooperate with senators, who were essential for running the empire. His disregard led to opposition, purges, and a vicious cycle of hatred between him and the aristocracy.

Was Nero’s interest in the arts accepted at the time?

Nero’s public performances were shocking to Roman elites who saw them as inappropriate. He forced senators to attend his singing and dancing, which broke traditional decorum for their class.