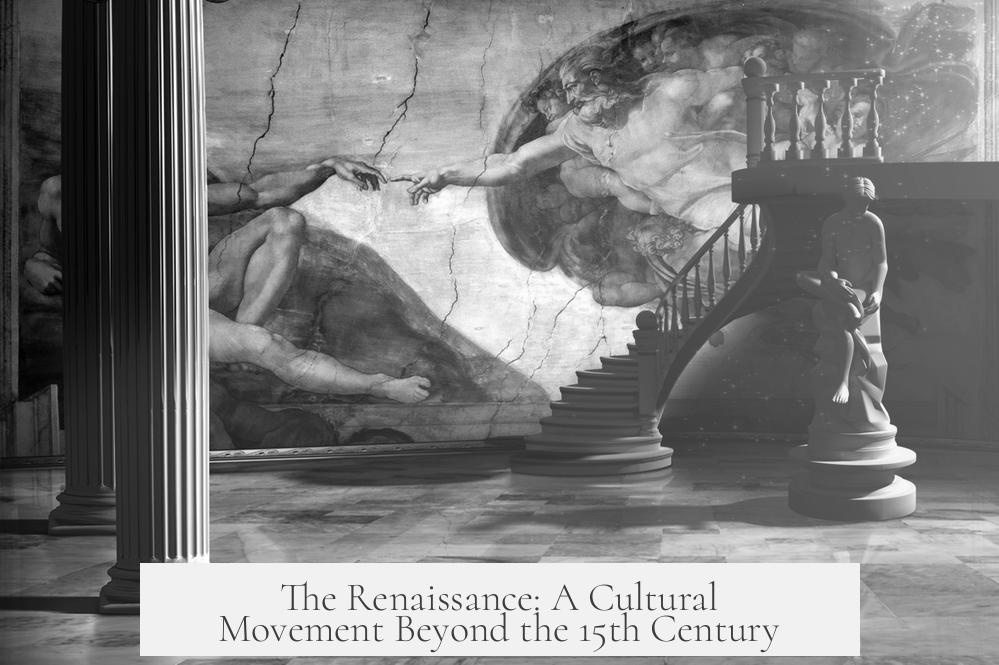

The Renaissance is best understood as a cultural movement centered on the revival and conscious imitation of classical Greco-Roman art, literature, philosophy, and humanism, rather than strictly as a fixed chronological period. It emerged prominently in Italy before spreading throughout Europe, marking a shift in thinking and artistic expression that distinguishes it from the Medieval period, yet its start and influence vary widely by region.

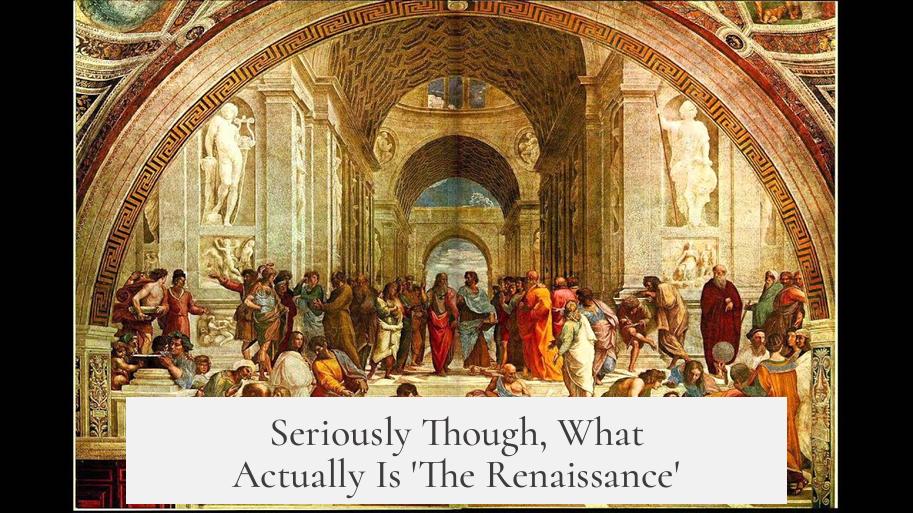

The Renaissance is often defined by two main frameworks: as a periodization of time and as a cultural movement. When treated purely as a period, many scholars tie its beginning to the fall of Constantinople in 1453. From this point of view, events occurring one or two centuries earlier do not belong to the Renaissance proper. However, this strict timeline overlooks important early developments and regional differences.

When seen as a cultural movement, the term Renaissance gains more nuance and relevance. It represents a conscious attempt to revive and emulate classical antiquity’s artistic, literary, and philosophical ideals. This revival is particularly marked by classicism, not simply admiration for ancient works but an active effort to adapt classical models in new creations.

Italy is widely regarded as the birthplace of the Renaissance, with roots tracing back to the 13th century. Artists such as Niccolò Pisano and his son Giovanni Pisano, along with Arnolfo di Cambio, introduced a new naturalism in sculpture and architecture that departed from preceding medieval styles. These early innovations laid the groundwork for the flourishing of Renaissance art and ideas in the 15th century.

However, the Renaissance did not occur simultaneously across Europe. Different regions experienced the movement at different times. For example, Renaissance humanism reached France around the mid-15th century, with figures like Jacques Lefebvre d’Etaples taking a leading role. Spain saw the influence of Renaissance ideas partly through political and cultural exchanges with the House of Aragon, also delayed compared to Italy.

This varying timeline produces a diachronic view of Europe, where in the late 13th century, Northern Italy embraced Renaissance ideals while other parts like London remained more medieval in outlook for centuries longer. The complexity of these uneven progressions challenges simplistic periodizations based solely on dates.

Distinguishing the Renaissance from the so-called Dark Ages involves recognizing shared continuity alongside critical shifts. Although some perceive medieval art as inferior to Renaissance work, the break from realism and naturalism characteristic of Greco-Roman art was intentional. The medieval period maintained a consistent love for Latin authors such as Cicero, Seneca, and Vergil, with classical scholarship surviving through cathedral and monastic schools.

Earlier revivals, like the Carolingian Renaissance (circa 750-850), had already nurtured scholarly activity under Charlemagne, preserving and transmitting classical knowledge. The later Renaissance expanded upon this foundation, notably reintroducing Greek language and philosophy more fully. Byzantine scholars such as Demetrios Kydones and Manuel Chrysoloras brought Greek learning to Italy before 1453, setting the stage for broader cultural renewal.

One of the most significant intellectual recoveries during the Renaissance was the reintroduction of Plato’s works beyond the Timaeus, along with other Platonic tradition thinkers such as Plutarch and Plotinus. This rediscovery influenced Western philosophy and culture profoundly, enriching the humanist framework and contrasting with the Medieval focus primarily on Aristotelian philosophy.

| Aspect | Medieval Period | Renaissance |

|---|---|---|

| Interest in Classics | Continuous admiration for Latin authors | Revival of Greek language and Platonic works |

| Art Style | Abstract and stylized medieval art | Return to naturalism and classical forms |

| Philosophy | Primarily Aristotelian | Rediscovery of Plato and Neoplatonism |

| Geographical Spread | Europe-wide, limited by conditions | Begins in Italy, spreads gradually to rest of Europe |

The Renaissance, therefore, is not simply a time block but a complex cultural awakening marked by regional variation and intellectual continuity with the past. It represents a deliberate modern renewal, involving art, literature, and philosophy, focusing on classical ideals with novel expressions.

- The Renaissance is primarily a cultural movement reviving classical antiquity in arts and ideas.

- It began earlier than 1453 in Italy, with important roots in the 13th century.

- Other European regions adopted Renaissance humanism later, creating a staggered timeline.

- The shift included the revival of Greek language, literature, and Platonic philosophy.

- Renaissance art consciously returned to naturalism, contrasting with both classical realism and medieval stylization.

- The term is most useful when seen as a broad cultural phenomenon rather than a strict time period.

Seriously Though, What Actually Is ‘The Renaissance’?

The Renaissance is not just a tidy historical time slot. It is a rich, tangled web of cultural revival that began as early as the 13th century in Italy and stretched unevenly across Europe over a few centuries. It’s a concept that defies simple calendar dates or border lines, calling for a more nuanced understanding if we want to avoid confusion and cliché.

So, what really defines this vibrant chapter famously called ‘The Renaissance’? Let’s unpack this colorful, complex era piece by piece.

The Renaissance: Time Period or Cultural Movement?

When most people think of the Renaissance, they imagine a distinct era between the “Dark Ages” and the early modern period. If you take this narrow approach — say, starting with the fall of Constantinople in 1453 — then anything before that doesn’t count. But this is where history gets tricky.

What if the Renaissance isn’t strictly about dates? What if it’s about ideas, art, and culture blossoming? In that case, defining it as a cultural movement makes much more sense and opens the door to rich interpretations beyond a simple timeline.

For example, Renaissance classicism—the conscious revival of Greco-Roman models in art, literature, and philosophy—is a vocabulary of ideas rather than an exact year on the calendar. This shifts Renaissance from a fixed era to a dynamic wave sweeping across European minds.

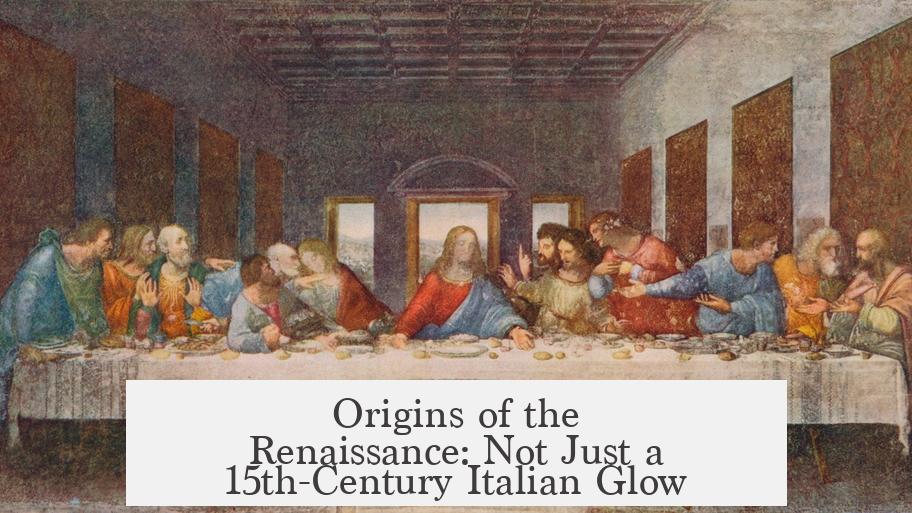

Origins of the Renaissance: Not Just a 15th-Century Italian Glow

It’s tempting to zoom in on Florence or Rome in the mid-1400s and say, “There it is!” But the roots of the Italian Renaissance stretch back at least to the 13th century. Artistic naturalism appeared early on in the works of sculptors like Niccolò Pisano and Arnolfo di Cambio. These artists broke from medieval abstraction and planted the seeds for what we now call the Renaissance.

Meanwhile, other parts of Europe were humming a different tune. In France and Spain, Renaissance humanism appeared slower. Jacques Lefebvre d’Etaples in France and intellectual exchanges between Aragonese branches brought the ideas in during the late 15th century, sometimes a hundred years later than in Italy.

It’s as if Europe was a vast theater where some stages lit up early, while others waited their turn. In 1297, Northern Italy might be reveling in a Renaissance-like cultural bloom, while London’s streets stroll through what we call the “Dark Ages.” Time, then, isn’t uniform but a patchwork.

Renaissance vs. Dark Ages: A Misunderstood Contrast?

The “Dark Ages” often get blamed for stifling progress, but that’s misleading. Scholars loved Latin classics all through the medieval period. Writers like Cicero and Vergil weren’t forgotten or dismissed—they were studied continuously, even if cultural expression took different shapes.

And before the Renaissance burst forth, there was the Carolingian Renaissance in the 8th and 9th centuries, an early revival effort under Charlemagne. This period fostered learning and classical scholarship when Europe was struggling to piece itself together after Rome’s fall.

So the Renaissance wasn’t a sudden “light switch” moment but part of a longer continuum of cultural recovery and transformation.

The Role of Greek Language and Philosophy in ‘Renaissance’

A defining feature of the Renaissance was the revival of Greek learning—philosophy, literature, and language. But this wasn’t completely new in the 15th century. Byzantine scholars like Manuel Chrysoloras, arriving in Italy before 1453, had already paved paths for Greek texts and ideas. Greek schools and textbooks circulated in Italy even before Constantinople’s fall.

The real change came with the full recovery of Plato and other thinkers in the Platonic tradition. Medieval Europe mainly knew Aristotle’s works and just one dialogue of Plato’s (the Timaeus). Suddenly, Renaissance scholars uncovered a treasure trove of Platonic writings and Neoplatonic philosophers like Plotinus. This influx rocketed Western thought into new directions.

So, What Does It Mean to Call Something Renaissance?

Is it a date? Not quite.

Is it a style? Partly.

Is it a shared mindset acknowledging and reviving classical ideas, art, and philosophy? Absolutely.

The Renaissance is better seen as a cultural horizon—a set of ideas and practices celebrating classical antiquity’s spirit, emerging unevenly through time and space.

You might ask, why should this matter now?

Understanding the Renaissance as a fluid cultural movement rather than a rigid era helps us see how ideas cross borders and evolve. It reminds us the past is never a simple timeline but a mosaic of influences. When we stroll through museums or read classic literature, recognizing the layered history enriches our experience.

Final Thoughts: The Renaissance Is a Living Story

The Renaissance invites us to rethink progress, idea transmission, and artistic vision. It’s about rediscovery—sometimes slow and regional, sometimes rapid and revolutionary.

If you ever stumble on the phrase “the Renaissance” in a book, remember, it’s less about strict dates and more about the revival of a worldview that shaped our modern sensibility. And it isn’t just dead history; it’s an inspiring lesson on how culture breathes, adapts, and reawakens.

Next time you hear someone say “Lol medieval art sucks,” you’ll know there’s actually a story behind those paintings—one honoring a deliberate choice, not a lack of intelligence.

So go ahead, dive into Renaissance books, art, and ideas with fresh eyes. It’s a patchwork tale of time, culture, and revival—far from dull, endlessly fascinating.

What exactly defines the Renaissance as a historical period?

The Renaissance is often linked to the fall of Constantinople in 1453 as a starting point. Events before that generally aren’t considered part of the Renaissance if we view it strictly as a time period.

How does the Renaissance differ across Europe?

It began earlier in Italy, with roots in the 13th century art and architecture. Other countries, like France and Spain, experienced Renaissance humanism a century or more later, showing uneven development across Europe.

Is the Renaissance just about rediscovering classical ideas?

Classicism is central to the Renaissance, involving conscious imitation of Greco-Roman culture. But it also included reviving Greek language and philosophy, which had started before 1453 due to Byzantine scholars.

How is Renaissance culture distinct from the Middle Ages?

The Renaissance consciously broke from medieval art’s style, returning to classical naturalism and philosophy. Yet, admiration for Latin authors persisted uninterrupted through the Middle Ages, showing continuity in learning.

Did any Renaissance elements exist before the 15th century?

Yes, early Renaissance traits appear in 13th-century Italian art. Also, the Carolingian Renaissance (8th-9th centuries) revived classical learning in Latin schools even though conditions were tough after Rome’s fall.