Tigers never naturally inhabited the islands of Japan. Despite their frequent depiction in Japanese artworks from the Edo era and earlier, tigers are not native to Japan. Japanese artists and people encountered tigers primarily through cultural transmission from China, limited direct contact via imported live animals, and symbolic references tied to religious and philosophical influences.

Tigers are absent in the wild in Japan. There are no records or evidence to suggest their presence as native fauna. As an 18th-century Japanese painter acknowledged in 1755, depicting tigers was challenging without living models. He admitted copying from Chinese painter Mao I’s works because real tigers could not be observed firsthand in Japan.

The tiger’s strong presence in Japanese culture derives from Chinese influence. In the Chinese zodiac, the tiger (Japanese: tora 虎) is one of the twelve animal signs and represents the west, autumn, and the metal element in the system called shisho (四象). The tiger is associated with the earthly realm contrasted with the dragon, which symbolizes the east and the heavens. This yin-yang duality deeply affected East Asian cultural and spiritual frameworks, influencing Japan.

Chinese philosophical and religious traditions like Buddhism, Daoism, Confucianism, and onmyodo (陰陽道, Japanese yin-yang cosmology) brought tiger symbolism to Japan. Tigers appear in old Japanese tombs marking the western direction. The 7th-century Tamamushi Shrine features a Buddhist panel showing the Mahasattva Jataka tale, where a prince sacrifices himself to save a starving tigress and her cubs. Such stories embedded tigers into Japanese religious narrative.

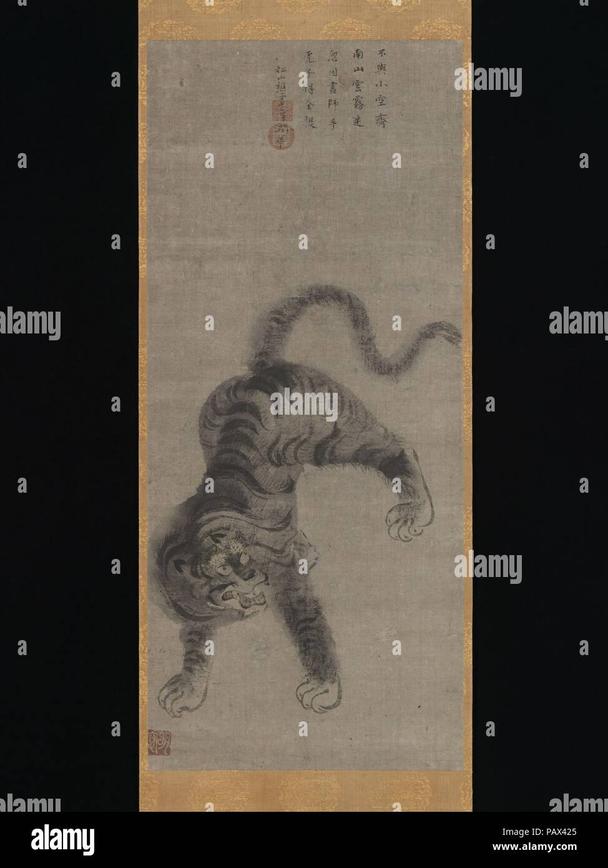

From the 14th century onward, tiger images arrived with Chinese ink paintings introduced by Zen Buddhist monks and warriors returning from the continent. These paintings symbolized power and legitimate political authority. Shogunal collections often housed tiger paintings as talismans invoking strength and protection.

Actual encounters with live tigers in Japan before the Meiji era were extremely rare. The first recorded live tiger arrived during Toyotomi Hideyoshi’s campaign against Korea in the late 16th century. Tigers captured in Korea or China were brought to Japan as prized exotic displays to showcase military success and international connections.

- Live tigers were reportedly seen in Kyoto’s riverbed entertainment district in 1648 and again during the Enpo era (1673-1681). However, historical records question whether these animals were genuine tigers or fabricated shows.

- During the Genroku period (late 17th to early 18th centuries), sideshow barkers advertised tigers allegedly imported from Holland, indicating limited but growing awareness of tigers through trade and foreign contact.

Japan’s isolation policy during the Edo period (1603-1868) restricted foreign animals and cultural imports, limiting direct observation of tigers. Artists mainly relied on earlier Chinese models and existing tiger depictions. Only a few books introduced via Dutch traders provided updated images of tigers and natural history, but artistic styles remained consistent with prior generations.

Two notable Edo era artists focused on tiger imagery: Kishi Ku (also known as Ganku) and his student and adopted son Kishi Renzan. Kishi Ku received a preserved tiger head as a gift from a Chinese merchant in Nagasaki in 1799, illustrating the continued symbolic and rare physical presence of tigers in Japan.

| Aspect | Details |

|---|---|

| Natural Habitat | No evidence of tigers living wild in Japan |

| First Live Tiger in Japan | 16th century, Toyotomi Hideyoshi era, captured during Korea invasion |

| Cultural Influence | Tiger symbolism imported from China via Buddhism, Daoism, zodiac |

| Artistic Sources | Chinese ink paintings, imported books, limited live models |

| Notable Artists | Kishi Ku (Ganku) and Kishi Renzan |

| Historical Display | Rare live tigers in urban entertainment districts; uncertain authenticity |

- Tigers are absent in Japan’s native wildlife.

- Cultural transmission from China introduced tiger symbolism before the Edo period.

- Live tigers reached Japan mainly through military campaigns and foreign gifts.

- Edo era artistic depictions relied on Chinese models and limited firsthand experience.

- Tigers held symbolic spiritual and political significance in Japan.

Did Tigers Ever Roar in Japan? The Curious Case of Tigers in Japanese Art Before the Meiji Era

Short answer? No, tigers never roamed the wild islands of Japan. Yet, you’ve probably seen those majestic striped beasts prowling across Japanese artworks from the Edo era and earlier, right? So, how did tigers sneak into the cultural landscape of a place without one single wild tiger? And how might a Japanese person have encountered a tiger before Japan opened up during the Meiji Restoration?

This story isn’t just about animals. It’s a fascinating tale weaving together philosophy, diplomatic relations, religious symbolism, and art history. Pull up a chair and let’s unravel the tiger’s journey into Japan’s mindset.

Tigers in East Asian Symbolism: More Than Just Stripes

First, tigers are a BIG deal in East Asia—not just for their physical prowess but for their cultural symbolism. In the Chinese zodiac, the tiger (tora 虎), one of the twelve signs, stands for the west, autumn, and metal. Tigers sit proudly as one of the shisho 四象, the four mythical beasts guarding the four cardinal directions. In this cosmology, the tiger faces off as the yin opposite to the dragon’s yang—tiger rules wind on earth, dragon commands clouds in the sky.

Military leaders especially admired tigers for their power and speed. Ancient Chinese classics like Tai Kung’s Rikuto 六韜 even dedicated a chapter to the “Tiger tactics,” focusing on strategy and equipment—talk about martial respect.

From China to Japan: Cultural Tiger Transfers

Now, Japan’s tiger obsession could not be based on local fauna—because there were no wild tigers here. The islands never provided a tiger habitat. Instead, tiger symbolism arrived bundled in cultural imports. From the 3rd to the 7th centuries during the Yamato era, Japan began its transformation into a unified state plotting to gain favor from the big neighbor, China.

Along with political envoy missions came Buddhism, Daoism, Confucianism, and yin-yang studies—the grand philosophical package that included tiger imagery. Japanese tombs dating back centuries display the tiger motif as a guardian for the west, showing how deeply symbolic tiger imagery had been assimilated.

Buddhism gave the tiger a spiritual twist. One famous image from the 7th century Tamamushi Shrine depicts a story where Prince Mahasattva sacrifices himself to feed a starving tigress and her cubs. That tale highlights compassion but also entrenched the tiger in Buddhist art and lore in Japan.

Painting Tigers Without Seeing Tigers: Edo Era Artistry

Between the 14th and 18th centuries, Japanese artists often looked to imported Chinese ink paintings for tiger inspiration. These works paired tigers with dragons to symbolize cosmic balance. Even though no one in Japan had seen a live tiger, the animals represented power, speed, and change. So, tigers became a staple in samurai collections and visual culture, embodying political and military clout just as the Emperor incarnated the dragon.

But wait—how accurate were these images? One famous Edo-era painter, active in the mid-1700s, confessed: “When I paint a tiger, how can I do it without ever seeing one? I must copy the works of the Chinese painter Mao I.”

Japan’s sakoku (closed country) policy under the Tokugawa shogunate sealed the islands off from much of the outside world between 1635 and 1853. No wild tigers, no real chance to study them up close. So, artists preserved a style that stayed remarkably consistent, relying on textbooks and Chinese paintings for tiger forms.

The Rare Reality of Live Tigers in Japan

Although tigers never lived naturally in Japan’s forests, historical records mention live tigers making a dramatic appearance from time to time.

During Toyotomi Hideyoshi’s aggressive 16th century expeditions to Korea, Japanese forces brought back exotic trophies, including tigers. These were the first live tigers ever recorded in Japan. Imagine the wonder: a creature from foreign lands, fierce and striped, roaming a Japanese stronghold for the very first time.

Later, in 1648, live tigers reportedly appeared in Kyoto’s riverbed entertainment district. Again, in the Enpo era (1673–1681), tigers appeared in Kyoto and Osaka, though some doubt whether they were real creatures or clever illusions. Sideshows touted tigers arriving from Holland, suggesting exotic animal trade routes through the Dutch East India Company presence at Nagasaki.

For the non-elite masses, these live tigers were likely rare spectacles, viewed during special exhibitions or fairs. The average Edo citizen’s tiger encounter was probably limited to artwork, stories, and symbolic uses.

Tigers, Tigers Everywhere—But Not a Single Wild One

So, if you stumbled across a tiger in Edo-period ink painting or a tiger motif on a samurai crest, remember: this beast is a cultural construct as much as an animal. It stood for power, protection, spirituality, and prestige—but not geography. No Japanese jungle or mountain forests ever hosted these big cats.

Still, tiger art flourished robustly, with entire schools dedicated to their depiction. The Kishi school produced notable tiger painters like Kishi Ku (Ganku) and his pupil Kishi Renzan. Kishi Ku even received an actual tiger head from a Chinese resident in Nagasaki in 1799. This trophy not only showed a tiger’s physical presence through a prized artifact but also tied Japanese artistic devotion to tangible reality, even if distant.

Practical Tips for Spotting Real Tigers in Historical Japanese Art

- Look for paired imagery of dragons and tigers in paintings—they symbolize cosmic balance.

- Notice the sharp stripes and the typical tiger stance influenced by Chinese ink styles; it’s less about naturalistic portrayal and more about symbolic power.

- Discover Buddhist panels, such as those at Tamamushi Shrine, where tigers highlight moral and spiritual teachings.

- Check period notes or artist statements that reveal where the artist found their tiger models—you might uncover fascinating stories about cultural transmission.

Conclusion: Tigers in Japan—Roaring Mostly in the Mind

In sum, the question, Did tigers ever inhabit the islands of Japan? gets a pretty direct answer: No—Japan had no wild tigers. If you spotted tigers in Edo era artwork or even earlier, these animals appeared because of intense cultural infusion from China, symbolic traditions from Buddhism and yin-yang philosophy, and later the rare occasions when live tigers were paraded or exhibited.

These majestic stripes represented more than just animals—they symbolized political power, spiritual depth, and cultural exchange across East Asia’s history. So next time you gaze at an Edo tiger painting, marvel at the blend of imagination and symbolism behind it. How cool is it that a country without tigers had such a fascination with them? Tigers, after all, were Japan’s invisible bridge to a bigger, interconnected world of ideas and artistry.

Curious—what other animals can you think of that have rich symbolic importance in place of physical presence? More fascinating stories await!