Surviving kamikaze pilots faced complex and often harsh treatment by Japanese society after World War II due to shifting public perceptions and political pressures. During the war, these pilots were idealized as supreme patriots willing to sacrifice themselves for the emperor. Afterwards, many survivors encountered ostracism, hostility, and silence imposed by authorities and society alike.

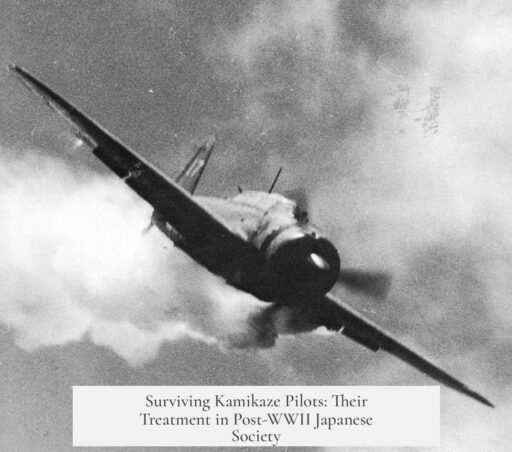

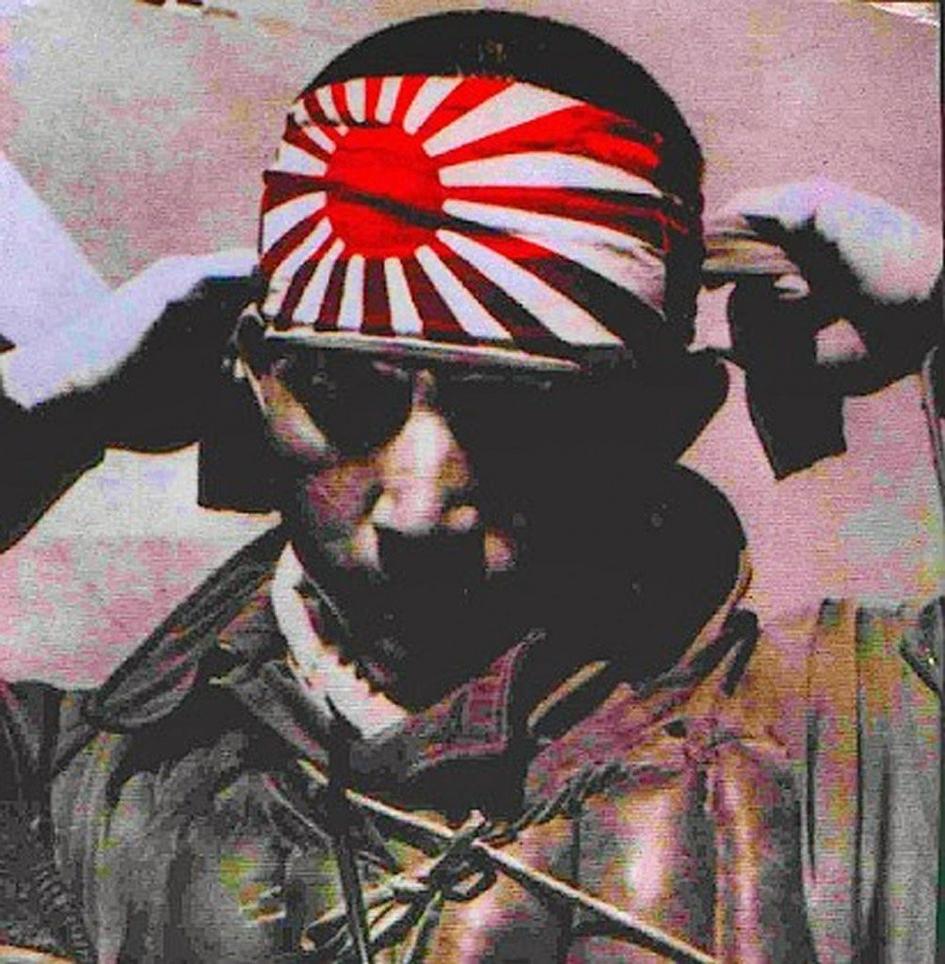

Japanese wartime propaganda cast kamikaze pilots as heroic figures, elevating them to revered status. The pilots were mainly very young, seen as skilled and noble warriors embodying Japan’s highest values. This romanticization created a powerful mythos around their sacrifice. The culture of honor deeply ingrained in Japan gave the missions a pseudo-religious aspect, valorizing self-sacrifice in service of emperor and nation.

However, the perception shifted abruptly after the war ended. Emperor Hirohito’s surrender broadcast marked a turning point. Initially, public sentiment expressed some sympathy toward the military personnel. Citizens were relieved that the war was over and felt frustration toward military leadership. Yet this sympathy was uneven and fragile.

The arrival of the U.S. occupation further altered views. The Allied forces publicized Japanese military atrocities across Asia, which deeply embarrassed many Japanese. Returning soldiers sometimes met resentment and aggression from civilians ashamed of wartime actions. This created a broader ambivalence toward the military as a whole.

Kamikaze pilots who survived their missions faced an especially difficult social position. Despite their prior veneration, their survival was seen by many as a sign of failure or cowardice. The public, influenced by military propaganda, believed that kamikaze pilots were supposed to die during their missions. Survivors challenged this ideal narrative and symbolized defeat and shame.

For example, Kazuo Odachi, a former kamikaze pilot, noted in his memoirs how neighbors expressed hostility toward him for still being alive. This reflected a widespread sentiment that kamikaze pilots who did not die in battle had dishonored themselves and the nation. The victorious Allied occupation administration further marginalized kamikaze imagery, labeling it irrational or insane to undermine any lingering military glorification.

Occupation authorities pressured survivors not to speak publicly about their experiences. Through 1952, many former pilots concealed their roles to avoid social ostracism. This silencing reflected both official policy and civilian discomfort with Japan’s militaristic legacy. It was a time marked by suppression and reinvention of national identity.

After the occupation ended with the Treaty of San Francisco, political conservatives in Japan sought to restore honorable notions of the Imperial military, including kamikaze pilots. From the 1990s on, efforts increased to reframe kamikaze as symbols of dedication and national pride. Museums and media contributed to this evolving narrative, though it remains controversial.

Between the 1950s and 1980s, scholars like M.G. Sheftall note that most Japanese still regarded the kamikaze concept as shameful. Understanding grew about coercion involved in pilot recruitment, adding sympathy for survivors. Yet resentment and mixed feelings persisted well into the late 20th century.

Despite social challenges, surviving kamikaze pilots retained official military status, entitling them to pensions after the war. This fact contrasts with their complicated civilian legacy, highlighting the disjunction between government recognition and social acceptance.

| Aspect | Details |

|---|---|

| Wartime view | Highly romanticized, symbolizing honor and self-sacrifice to emperor |

| Immediate postwar reaction | Mixed sympathy; emergence of frustration with military leadership |

| U.S. occupation impact | Public shaming of military; ostracism of survivors; suppression of kamikaze discourse |

| Survivor treatment | Hostility, accusations of cowardice, social isolation |

| Post-occupation shifts | Renewed conservative efforts to rehabilitate kamikaze image from 1990s |

| Official recognition | Survivors retained pensions as former military members |

- Kamikaze pilots were once idealized, then stigmatized postwar as symbols of defeat.

- Occupation forces suppressed kamikaze praise, pushing survivors into silence.

- Many civilians treated surviving pilots with hostility or suspicion.

- Post-occupation conservatives worked to restore honor to kamikaze legacy.

- Survivors kept military pensions despite social challenges.

How Were Surviving Kamikaze Pilots Treated by Japanese Society After WWII?

Surviving kamikaze pilots were treated with a complex mix of suspicion, shame, and silence during the immediate post-WWII years, only to have their legacy slowly rehabilitated decades later as Japan grappled with its wartime past and national identity. Intrigued? Let’s unpack this fascinating slice of history that often gets buried under broader WWII narratives.

First off, it’s essential to remember how highly romanticized kamikaze pilots were during the war. These young men, often barely out of their teens, were likened to the knightly figures of World War I fighter pilots. Their perceived intelligence, talent, and gentlemanly qualities cast them as Japan’s finest. The kamikaze mission had a deeply pseudo-religious tone—pilots willingly sacrificed themselves for the emperor, elevating their status beyond mere soldiers to near-mythical heroes.

But then, the war ended. Overnight, the glow around these pilots dimmed to near obscurity.

A Nation’s Conflicted Emotional Roller Coaster

When Emperor Hirohito’s surrender broadcast shocked the nation, public sentiment toward the military plummeted and veered wildly. Immediate post-war reactions leaned towards relief and sympathy—finally, peace after years of hardship. But things got muddier fast. The U.S. Occupation authorities aggressively pushed Japan to confront military atrocities committed during the war, especially those in Asian territories. This campaign seeded a deep ambivalence about the army and navy back home.

Imagine the confusion for returning soldiers. They came home to a country that once idolized them but now looked on them with a mixture of admiration, suspicion, or outright hostility. Some returned soldiers—called hikiagesha—were even assaulted by people who felt shame for their actions overseas.

The Kamikaze Pilot: From Hero to Pariah?

Surviving kamikaze pilots faced this divided society but often landed on the harsher side of public opinion. Many people saw them as symbols of shame and defeat rather than bravery. This perception is highlighted vividly in accounts like those of Kazuo Odachi, a former kamikaze pilot who flew seven missions and was preparing for an eighth when Japan surrendered. While Odachi himself survived, to the general public, returning alive meant failure. The propaganda machine during the war had aggressively portrayed kamikaze attacks as near-unfailingly successful. So, pilots who returned were often assumed to be cowards who shirked their ultimate duty.

“To many, the returned kamikaze pilot was not a hero but a living symbol of national defeat and personal failure.”

This was no small social stigma. It was real and often expressed overtly. A scene from the film Godzilla Minus One captures a pilot being confronted with hostility just for surviving, a situation that really wasn’t rare at all. Survivors were often forced into silence about their wartime roles. Even the U.S. General Headquarters (GHQ) pushed this narrative, labeling kamikaze missions as “insane” to reduce admiration and glorification.

The Silencing and Ostracism of Pilots

With the strong directive—not just social, but official—to keep quiet, many surviving pilots hid their pasts. Kazuo Odachi’s memoirs explain how pilots were told expressly to avoid discussing their experience or even mentioning that they were pilots. The years from 1945 until 1952 were harsh for these men. Ostracism was commonplace, turning once-celebrated warriors into shadowed figures in society.

But here’s a twist: despite this social alienation, the surviving pilots still received military pensions. They were still legally members of the imperial military. Think of it as a grudging recognition by the state, even if society at large looked away.

The Shift After the Occupation: Reclaiming Honor

Things began to change after the U.S. occupation ended in 1952 and the Treaty of San Francisco in 1951 came into effect. Japanese conservatives found space to reassert a more positive image of the military and the kamikaze pilots. What had once been labeled ‘shameful’ started to be reinterpreted as honorable sacrifice—in part due to a deeper understanding of the coercive methods used to recruit kamikaze pilots. People recognized that many of these young men had little to no choice.

M.G. Sheftall’s Blossoms in the Wind shows this shift well. From the 1950s through the ’80s, a complex mixture of shame and sympathy marked popular perspectives. The tide began turning more strongly toward sympathy and respect from the 1990s onward. Media representations and museum exhibits have been instrumental in reshaping public memory by commemorating kamikaze pilots’ bravery while acknowledging the tragic nature of their missions.

What Does This All Tell Us?

This complicated journey—romanticized heroes to social pariahs and back toward honored, if still controversial, figures—reflects Japan’s larger struggle to come to terms with its militaristic past.

For surviving kamikaze pilots, the aftermath of WWII was far from a hero’s welcome. Instead, it was a forced retreat into shadows, silenced stories, and sometimes outright scorn. Their pensions were a lonely reminder of a society that admired their sacrifice but struggled to reconcile it with the stigma of defeat and the horrors of war.

Yet, over time, a more nuanced collective memory has emerged. It questions simplistic narratives and underscores the complex realities of young men caught in the storm of war, where notions of heroism and shame coexisted.

Some Food for Thought

- How should societies remember soldiers who fought for controversial causes?

- What role do propaganda and post-war narratives play in shaping public memory?

- Can true reconciliation ever occur without confronting uncomfortable truths?

These questions remain as pressing today as the stories of the kamikaze pilots themselves.

Summary Table of Key Points

| Period | Public Perception | Treatment of Pilots | Additional Notes |

|---|---|---|---|

| During WWII | Highly romanticized as heroic, gentlemanly knights of the sky | Very honored and revered in society | Kamikaze missions seen as ultimate sacrifice for the emperor |

| Immediately Post-War (1945-1952) | Varied: sympathy mixed with hostility and shame | Ostracism, silencing, social stigma, verbal and sometimes physical hostility | GHQ labeled kamikaze missions as insane, pilots told to keep quiet |

| Post-Occupation (1952 onward) | Gradual rehabilitation, mixed feelings with growing conservative efforts to honor pilots | More public recognition, emergence of museums and media celebrating legacy | Kamikaze pilots receive pensions throughout |

Ultimately, the story of surviving kamikaze pilots challenges us to look beyond simple labels of heroism or shame. It invites reflection on the costs of war, the power of memory, and the difficult journey toward understanding and reconciliation.