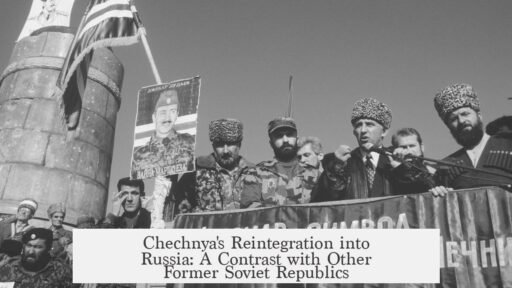

Chechnya was reintegrated into Russia because it was an autonomous republic within the Russian Soviet Federated Socialist Republic (RSFSR), not a separate Soviet Socialist Republic (SSR) like the Baltic or Central Asian republics. This difference defined their legal and constitutional statuses during the collapse of the USSR, shaping their paths afterward.

Chechnya’s status before the Soviet Union’s fall sets it apart. Unlike the Baltic states or Central Asian SSRs, Chechnya was an Autonomous Soviet Socialist Republic inside the RSFSR, which itself became the Russian Federation. The Soviets viewed Chechnya as part of Russia’s federal structure. The Baltic and Central Asian republics were separate SSRs within the Union. This gave the latter distinct legal rights to secede, recognized under the 1977 Soviet Constitution. Chechnya lacked this right formally because it was not a full republic under Soviet law.

During the late 1980s and early 1990s, many Soviet republics declared sovereignty to gain control over their laws and resources. This “war of laws” did not immediately equal independence, except for Lithuania, which clearly declared it. The Baltic states, such as Estonia, Latvia, and Lithuania, had historic claims and international sympathy, especially since their initial Soviet incorporation was not widely recognized. They worked toward full independence outside Russia.

The Soviet Union dissolved officially in December 1991 when leaders from Russia, Ukraine, and Byelorussia signed the Belovezha Accords, declaring the USSR’s end. Soon after, eleven other republics accepted these terms in the Alma-Ata Protocol. Russia emerged as the USSR’s legal successor. It gained the permanent seat on the UN Security Council, control of nuclear weapons, and assumed much of the Soviet debt. The Russian Federation retained the RSFSR’s constitution, with substantial amendments, and kept the federal structure of diverse subject entities inherited from the Soviet nationalities policy.

After the USSR’s breakup, all former ASSRs inside Russia, including Chechnya and Tatarstan, adopted their own constitutions and presidents. Their exact relationship with Moscow was unclear initially. Most signed a Federation Treaty with Russia in March 1992, affirming their place within the Russian Federation.

Chechnya and Tatarstan notably refused this treaty. Tatarstan negotiated extensively and accepted union membership in 1994 with some degree of autonomy. Chechnya outright sought independence, leading to two devastating wars starting in 1994. The Russian government viewed Chechnya’s bid as a threat to the federation’s territorial integrity and was prepared to use force to reintegrate it.

Under President Vladimir Putin, Russia strengthened central authority significantly. The federal subjects remained officially part of a federation, but Moscow centralized power through presidential plenipotentiaries managing federal districts. This reduced the autonomy of regions on paper and in reality, consolidating federal control. The reintegration of Chechnya was part of this policy.

Putin’s administration emphasized preventing further fragmentation of Russia. Chechnya’s violent struggle for independence motivated a crackdown to deter other regions from secession. The wars ended with Moscow regaining effective control over Chechnya. Today, Chechnya remains a republic within the Russian Federation, governed by a Moscow-aligned local leader.

In contrast, the Baltic and Central Asian republics had clearer and internationally recognized claims to sovereignty as former SSRs of the Union, not subordinate parts of Russia. Their legal right to secede, political will, and international recognition enabled them to become independent countries after 1991. Russia accepted this new reality while guarding against fragmentation within its own borders.

| Aspect | Chechnya | Baltic & Central Asian Republics |

|---|---|---|

| Status before 1991 | Autonomous Republic inside RSFSR (Russia) | Soviet Socialist Republics within USSR |

| Right to Secede | None officially | Constitutional right under 1977 USSR Constitution |

| International Recognition | Viewed as part of Russia | Recognized as distinct entities post-USSR |

| Post-USSR Path | Conflict, wars, reintegration into Russia | Declared and gained independence |

| Russian Policy | Military reintegration, federal control | Accepted independence |

- The key distinction is Chechnya’s legal status as a federal subject within Russia, unlike SSRs which had constitutional secession rights.

- The collapse of the USSR legitimated the independence of SSRs but not autonomous republics inside RSFSR.

- Chechnya’s attempts to secede sparked violent conflict, prompting Moscow’s forceful reintegration policy.

- Putin’s administration strengthened Moscow’s grip on federal subjects, ending regional separatism efforts within Russia’s borders.

- Baltic and Central Asian republics became sovereign states due to their prior SSR status and international recognition.

Why Did Chechnya Get Reintegrated into Russia But Other Past Republics Didn’t Like Some of the Baltics or Central Asian Republics?

Simply put: Chechnya was always part of Russia under federal law, while the Baltics and Central Asian republics were parts of the Soviet Union as separate republics. This legal distinction shaped their paths after 1991, making Chechnya’s reintegration a matter of asserting federal control and the others’ independence recognized internationally.

Sounds dry, right? But the story behind post-Soviet politics is more like a chess game with historical nuances and power moves.

The Big Legal Difference: Chechnya vs. Soviet Socialist Republics

The Soviet Union was a patchwork of Soviet Socialist Republics (SSRs) and smaller autonomous republics. Chechnya was one of the latter—a tiny autonomous Soviet Socialist Republic (ASSR) inside the Russian Soviet Federative Socialist Republic (RSFSR), which itself was a constituent republic of the USSR. In contrast, the Baltic states (Lithuania, Latvia, Estonia) and Central Asian republics (Kazakhstan, Uzbekistan, etc.) were full-fledged SSRs, directly part of the Soviet Union, but not part of Russia.

When the USSR unraveled, these SSRs declared sovereignty or outright independence. However, Chechnya tried to declare itself an independent republic in 1991, which Russia did not recognize. Russia, and by extension the international community, still considered Chechnya part of the Russian Federation. This legal status difference meant that Chechnya’s bid for independence was seen as a domestic rebellion, while the SSRs’ independence was a matter of dissolving a union.

Constitutional Rights: Who Could Leave and Who Couldn’t?

The 1977 Soviet Constitution granted Soviet Socialist Republics the *right* to secede, though it was never expected to be exercised casually. This legal provision opened the door for SSRs to claim independence when the USSR gasped its last.

Chechnya, as an ASSR, did not have this constitutional right to secede. That’s a crucial point. Chechnya’s declaration wasn’t just bold; it was *illegal* under Soviet and Russian federal law.

War of Laws: The ‘Sovereignty’ Talks

In 1990 and 1991, the Soviet SSRs engaged in a “war of laws,” asserting their own legal systems over union-wide laws. They claimed resources and sovereignty, essentially positioning themselves as nearly independent states. The Baltic states even declared full independence early on, ignoring the Soviet power structures.

Chechnya didn’t have this room to maneuver legally. It was stuck inside Russia’s borders, so its sovereignty push was met with political and military resistance.

The USSR Breaks Up: Who Leaves and Who Stays?

In December 1991, heads of USSR republics—most notably Russia, Belarus, and Ukraine—signed the Belovezha Accords, officially dissolving the USSR. Soon after, 11 of the 15 former republics signed the Alma-Ata Protocol, acknowledging Russia as the USSR’s legal successor.

At this point, the Baltics and Central Asian republics’ independence received broad international recognition. Russia took over the USSR’s assets, debts, nuclear arsenal, and Security Council seat. The Commonwealth of Independent States (CIS) formed as a loose cooperative entity among former Soviet republics.

Chechnya did not get this international recognition as an independent state and remained legally tied to Russia.

Russia as the Successor State: Keeping Federal Subjects Intact

Technically, the RSFSR didn’t vanish with the USSR. It transformed into the Russian Federation, shedding Soviet terminology but maintaining its 1978 constitution with amendments. The federal subjects, including republics, oblasts, and autonomous regions, survived.

Chechnya continued as one of those federal subjects, despite its push for independence. Other autonomous republics chose to stay in Russia, in varying degrees of union.

Stubborn Rebellions: Chechnya and Tatarstan Shake Things Up

Unlike most ASSRs, both Chechnya and Tatarstan refused to sign the Russian Federation’s 1992 Federation Treaty. Tatarstan compromised after protracted talks, agreeing to remain within Russia in 1994. Chechnya, however, declared outright independence, prompting brutal conflict.

This refusal and subsequent wars made Chechnya exceptional. The Russian government fought to prevent further fragmentation of its territory during the 1990s, escalating into the First and Second Chechen Wars.

Putin’s Presidency: Centralizing Power and Quelling Separatism

Many of the unresolved tensions smoothed out under Vladimir Putin, whose presidency began in 2000. He revamped federal control, imposing “presidential plenipotentiaries” over federal districts—extra-constitutional positions designed to keep regional powers in check.

Putin’s administration reasserted central authority strongly, sidelining federalism on paper in favor of real political control. This move ended much of the separatist chaos that had boiled throughout the 1990s, including in Chechnya.

Chechnya’s Reincorporation: Fight or Stay? Russia Chose Fight

The story of Chechnya’s reintegration is mostly one of force. The republic wanted independence enough to fight for it. Russia chose not to let Chechnya slip away—launching military campaigns to bring the territory back under Moscow’s control. This contrasts sharply with the Baltics and Central Asian republics, whose independence Russia and the world eventually accepted.

Comparing Paths: Why Other Former USSR Republics Didn’t Rejoin Russia

- The Baltics were forced into the USSR—a fact they never legally recognized. Their demands for independence were rooted in restoring sovereignty lost during Soviet annexations.

- Central Asian republics gained international recognition as sovereign nations, with legal rights to secede from the USSR, making their post-1991 independence broadly accepted.

- Chechnya’s claim lacked both international recognition and legal grounds under Soviet and Russian laws, positioning it as a rebellious region rather than a sovereign state.

Final Thoughts: What Does This Mean Today?

Chechnya’s reintegration shows the limits of federal fragmentation within Russia. The Kremlin chose to secure its internal borders by force and strong centralized government. The Baltics and Central Asian republics highlight how international law and constitutional rights shape national self-determination.

So next time someone wonders why some Soviet republics are independent and others stayed or were forced back, remember—it’s about legal status, international recognition, and political power plays, not just who shouted loudest.

Curious about other post-Soviet dynamics? The interplay of law and force remains a riveting topic in geopolitics today. And Chechnya’s case is a particularly sharp lesson in how history, law, and power collide.