The belief that medieval Europe favored overweight bodies as the beauty ideal is inaccurate. Actual medieval beauty standards emphasized a slender, youthful appearance rather than excess weight. This misconception partly arises from confusion about historical clothing styles and social signals linked to wealth and status.

In medieval Europe, there was no widespread cultural preference for being overweight. Instead, people prized slimness, with women admired for slim legs, narrow waists, and high breasts. Men’s fashion favored long, lean legs, broad shoulders, and narrow waists.

- Women’s broad hips were valued more than in later Western beauty trends, focusing on natural curves rather than excess bulk.

- For men, slender, elongated lines were a fashion ideal, highlighted by tailored clothes such as doublets and hose.

- Shapely slimness symbolized youth and beauty, acting as a counterpoint to heaviness, which was associated with age and losing vitality.

The idea that medieval people preferred overweight figures likely stems from misunderstandings about clothing and social norms of the era. Wealthy individuals displayed status by wearing many layers of clothes, often heavily padded and structured with pleating, fur linings, and supportive garment construction like stays or underskirts. This layering added volume to their appearance, which could be mistaken for larger body size.

This clothing bulk created a visual impression of “chunkiness,” but it did not reflect actual body weight or shape. Garments were often tailored with intricate techniques to produce fashionable silhouettes—tailors shaped clothing to create desired contours, regardless of the person’s natural body type.

Medieval fashion lacked modern elements such as the weight loss industry or standardized clothing sizes. Clothes were hand-made to fit the individual’s measurements carefully, not to fit a universal size chart or enforce a particular weight standard.

There was male anxiety about weight, especially regarding aging. Prominent examples like Matthaüs Schwarz, a 16th-century figure known for detailed fashion records, expressed concern about gaining weight because it symbolized loss of youth and attractiveness. Men actively tailored their clothing to project an appealing shape, often enhancing contours with padding or structured garments such as the “peascod belly” in later fashion periods.

The Renaissance period is often mistaken as medieval but warrants separate consideration. In the Renaissance, particularly in 16th and 17th-century art, fuller-figured women appear in paintings by artists like Peter Paul Rubens. These figures celebrated curves and fleshier bodies, reflecting evolving ideals of sensuality. However, this was specific to certain artworks and not a universal standard of attractiveness.

Even depictions of sex workers in early modern Dutch art show a range of body types, often with soft shoulders and faces rendered erotically but not exclusively plus-sized. This variety rejects the notion of overweight as a broad beauty ideal.

| Aspect | Medieval Beauty Ideal | Common Misconception |

|---|---|---|

| Body Weight | Valued slim, youthful figures | Preferred overweight figures |

| Clothing Impact | Layered, structured clothes add volume | Misread as natural body size |

| Fashion Variation | Contoured shapes tailored by tailors | One-size ideal of corpulence |

| Renaissance Influence | Later emergence of fuller figures in art | Confused with medieval norms |

| Social Signals | Wealth shown through clothing, not weight | Weight mistakenly tied to status |

To sum up the facts:

- Medieval Europe favored slender, youthful bodies over overweight figures in ideals of beauty.

- Heavy-looking clothing and padding often cause modern observers to confuse medieval fashion with body size.

- Clothing styles emphasized tailoring and shaping to convey fashionable contours, not natural heaviness.

- Male fashion contained anxieties about weight linked to aging, favoring slim forms.

- Renaissance art later introduced fuller body types, which are not representative of medieval tastes.

Is It True That the Beauty Ideal in Medieval Europe Was to Be Overweight?

The short answer? No, it’s a myth that medieval Europe prized being overweight as the ideal of beauty. While some Renaissance paintings popularized fuller figures, medieval beauty standards mostly favored slimness and youthful shapes — not the doughy-cheeked look you might imagine.

That’s a relief if you thought people back then were trying to be modern “Instagram influencers” sporting #cottagecore curves. Let’s dive deeper and bust the myth with some fascinating facts.

Why the Myth Exists: Volume and Wealth, Not Weight

One reason people imagine medieval beauty as overweight is because of how generously people dressed. Tudor and late medieval fashion often involved layers upon layers of fabric—think cartridge pleating, fur linings, and thick shifts underneath gowns and doublets. This could easily add significant bulk and volume to a person’s silhouette.

Want to flaunt your wealth back then? Forget dieting; just wear tons of rich fabrics and fancy undergarments. No skinny jeans or tight dresses trying to show off a figure. Adding physical pounds wasn’t necessary.

Also, clothes were hand-sewn to fit individual bodies, as standardized sizing simply didn’t exist. So if you look plump in paintings or portraits, likely a large part is the clothing and underlying structure, not a natural body shape.

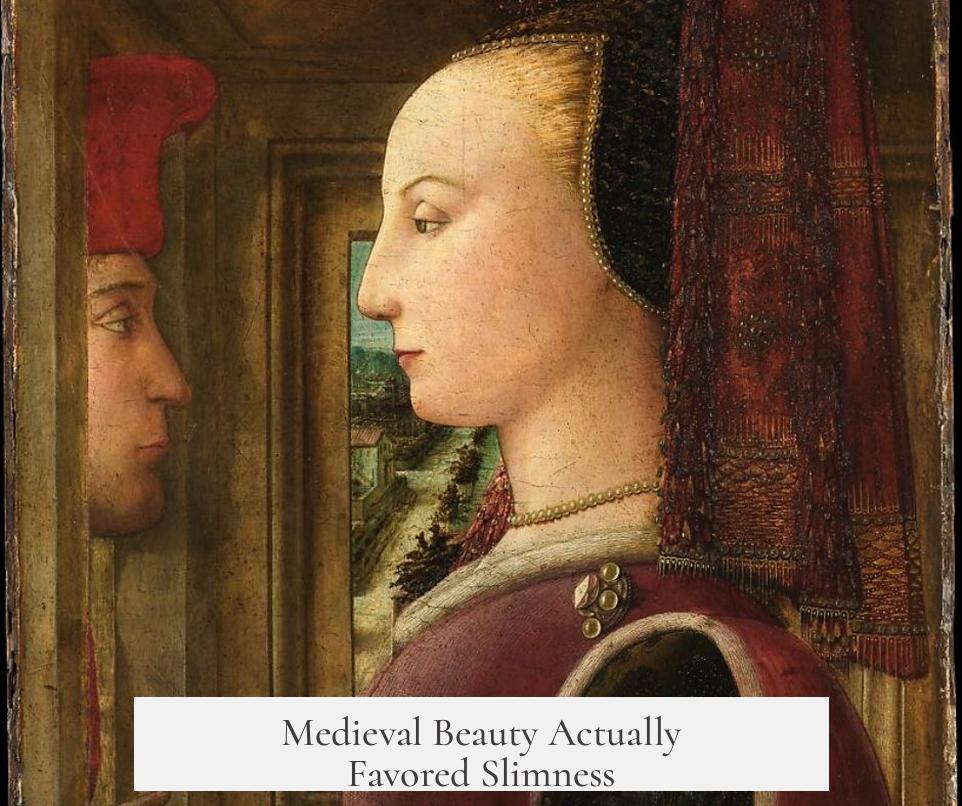

Medieval Beauty Actually Favored Slimness

Contrary to popular belief, slimness was prized for much of the Middle Ages. Women were admired for slim legs, narrow waists, and high breasts. Men’s fashion emphasized long, lean legs, broad shoulders, and narrow waists. Notice the focus on slenderness and elegant lines.

In fact, there wasn’t any “heroin chic” extreme thinness like we might associate with some modern beauty crazes, nor did people aspire to look like those suffering from plague. Slimness was linked to health, youth, and vitality, distinct from the heaviness associated with age.

Speaking of age, slimness was a sign of fashionable youthfulness. People typically associated weight gain with getting older—and losing some charm.

Gender Differences Made a Difference

Women’s beauty standards included specific shapes, especially around the hips and belly. Broader hips were seen as a sign of fertility and beauty. This creates a subtle nuance in the “slimness ideal” — it wasn’t about being rail-thin everywhere but having appealing curves, especially for women.

Men, on the other hand, were more about the long, lean silhouette. But even then, they played with fashion tricks like doublets and hose tailored for ideal shapes—sometimes shaped and padded to create fashionable contours like the famous “peascod belly.” This was a fashionable puffed-out belly look, designed and reinforced by tailoring, not natural weight gain.

The Renaissance Shift: From Slim to Full-Figured

The image of full-figured beauties really took off during the Renaissance, not the medieval period. Painters like Peter Paul Rubens famously depicted “full-fleshed” women with soft curves, often glorifying the sensual, fleshy body.

But even this wasn’t universal or a strict rule—it was an artistic style reflecting specific ideals of sensuality infused with cultural context rather than everyday life or typical beauty expectations.

In fact, even detailed art depicting 16th and 17th-century Dutch sex workers shows these figures as varied in body type—not necessarily “plus-size” in today’s terms. Soft features like round shoulders and chins were eroticized, but size varied.

What About Men’s Weight? Anxiety and Fashion

Late medieval men did worry about weight, but not in the way modern diets obsess over pounds. A famous example is Matthaüs Schwarz, a 16th-century fashion plate who feared gaining weight because it symbolized aging and loss of youthful charm.

Men relied heavily on tailors to craft garments that gave their bodies the fashionable shapes of the moment. This was a way to maintain the illusion of a fit, youthful body—padding or shaping included—regardless of whether the man was naturally slim or not.

Why the Myth Is So Persistent

So, why do many still believe medieval Europe loved overweight beauty? A few reasons:

- Visual Misinterpretation: The voluminous clothing and padding in portraits can look like natural bulk.

- Renaissance Paintings: Later artworks show full-figured beauties, so people conflate Renaissance beauty ideals with the whole medieval period.

- Modern Nostalgia and Simplifications: People like to imagine romanticized, plump “medieval” beauties as symbolic of abundance and health before modern dieting crazes.

But when you look closer, it’s clear medieval ideals leaned toward slimness, youthful elegance, and tailored presentation.

A New Angle: What Can We Learn from Medieval Beauty Ideals?

The medieval world shows us how beauty standards depend heavily on culture, technology, and social context. With no mass-produced clothing sizes or weight-loss crazes, the medieval look focused on custom-fit clothes emphasizing lines and shape rather than size alone.

Also, fashion was a game of illusion. Clothing padded or designed shapes to project wealth, youth, and style. Weight, then, was not a blanket standard but one component in a much richer tapestry of appearance.

If anything, medieval beauty ideals remind us that the perception of attractiveness is fluid and heavily influenced by societal factors, much like today.

So, Does Overweight Equal Beauty in Medieval Europe? Not Quite

Bottom line: Medieval Europe did not universally prize being overweight as the beauty ideal. It was slimness, tailored elegance, and youthful curves that held sway. The “chunky” visuals we often associate with the period largely come from clothing style and later Renaissance art, rather than medieval standards themselves.

Next time someone tells you the medieval ideal was all about being overweight, you can confidently say: “It’s complicated, but mostly no.” After all, history deserves clarity—even when the tale is tempting!

Curious about how fashion and body ideals evolved afterward? Stick around, because the Renaissance brought new ideas, curves, and yes, even more complexity to what it meant to look good.